Timeless Allure

Greenfield through the centuries

BY David A. Norris

Reflecting history from four centuries and providing an echo of the cypress forests and wetlands that flourished for thousands of years in North Carolina, Greenfield Lake is a unique part of Wilmington’s landscape.

Naturalist Paul Bartsch, an assistant curator at the U.S. National Museum (part of the Smithsonian Institution), wrote a description of Greenfield when he visited the lake in 1906 in search of rare freshwater mollusks.

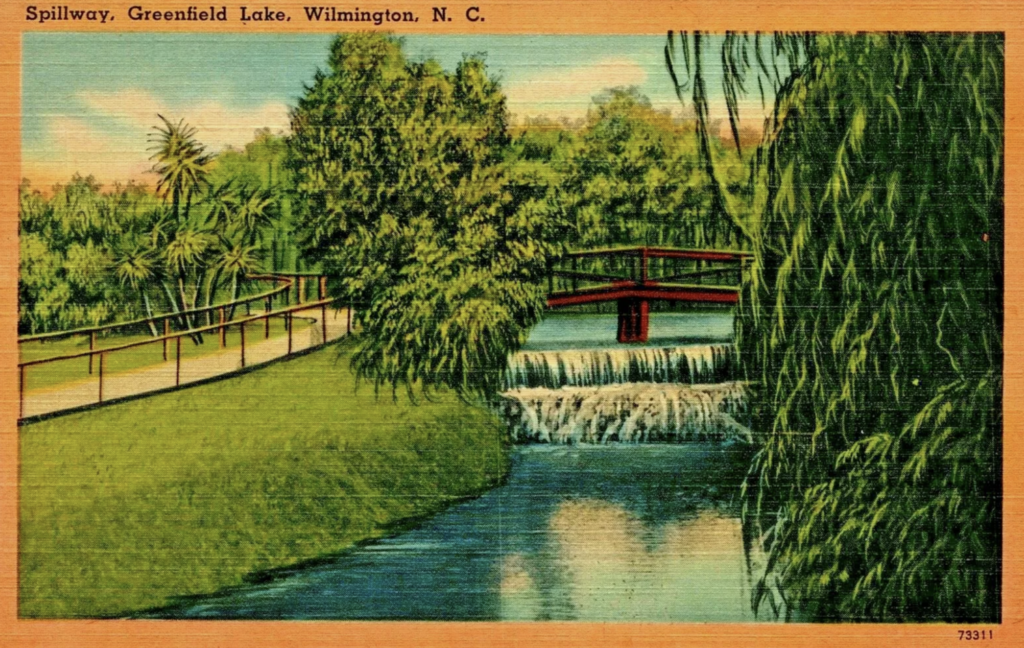

“The pond is formed by a broad earthen milldam, about 20 feet high, which banks up water between sand dunes, inundating the low-lying ground, and transforming it into a lake, the digitations of which extend back for some 3 miles,” he wrote. “A large portion is fringed with cypress trees, and there are several cypress-covered islands in it. The trees are not large, hardly more than a foot in diameter, and all are draped with large festoons of Spanish moss.”

Through a land grant as well as real estate purchases, Dr. Samuel Green (1707-1771) acquired what became Greenfield Lake by the 1750s. He named his plantation there Greenfields, and he also owned a nearby plantation called Greenhill. Greenville Sound, where the doctor also owned land, is named for him as well.

It seems that the original dam at Greenfield, which created the lake, was built while Green owned the property. The water backed up by the dam was released to flood ricefields on the plantation located on the low-lying land north of the half-mile of Greenfield Creek between the dam and the Cape Fear River.

Quite long ago, a mill was constructed near the dam. The Collet map of 1770 shows Green’s sawmill located south of Wilmington.

Born in Liverpool, England, Green practiced medicine for about 30 years after his arrival in Wilmington circa 1740. A few years before Green obtained Greenfield, Spanish privateers attacked and occupied Brunswick Town for a few days in 1748, during King George’s War. The privateers withdrew after their rather inappropriately named ship Fortuna exploded in the Cape Fear River. At New Hanover County’s expense, Green treated half a dozen prisoners that survived the explosion. After his death, Green was buried in Saint James Churchyard, where his gravestone is still readable today.

Green’s son William M. Green sold the plantation in 1844 to Edward B. Dudley, the former governor of North Carolina who lived in the Dudley Mansion on Front Street in Wilmington.

T.C. McIlhenny subsequently owned Greenfield. He listed the property in 1855, stating that his holdings included “170 to 180 acres of rice land, and about 300 acres of upland.” Greenfield was a landmark appearing on many early maps of the Cape Fear River and New Hanover County. Rather than a grand manor house, McIlhenny noted only that the place included “a dwelling house, with the necessary out houses.” Despite advertising the land for sale, McIlhenny still owned Greenfield a year later when he opened a whiskey distillery on the property after the Civil War.

The distillery had its share of trouble. During the Christmas season of 1880, thieves stole three stills and one worm (the copper tube that allows the spirituous vapor to condense). Police caught some of the thieves, who had already sold some of their loot as scrap copper.

Federal agents raided the distillery in 1902. The operators had added a secret tube to draw part of their product into an underground tank so they could sell the whiskey without paying tax.

Changes in ownership created some confusion over the name of the cypress-shaded body of water south of old Wilmington. Most Wilmingtonians called it Greenfield Pond, while others called it McIlhenny’s Pond. Only after about 1911 did the Wilmington press consistently refer to the place as Greenfield Lake. Likewise, the mill was known by various names according to its ownership.

Greenfield also has a long history as a spot for recreation and leisure. As early as 1806, a newspaper ad warned “persons (who) continue to hunt and hawl [sic] away wood &c. from the lands belonging to Greenfield Estate” of legal prosecution. Again, in 1845, the owners warned against hunting and fishing at “the Greenfield Place.” But, as they say, if you can’t beat them, join them.

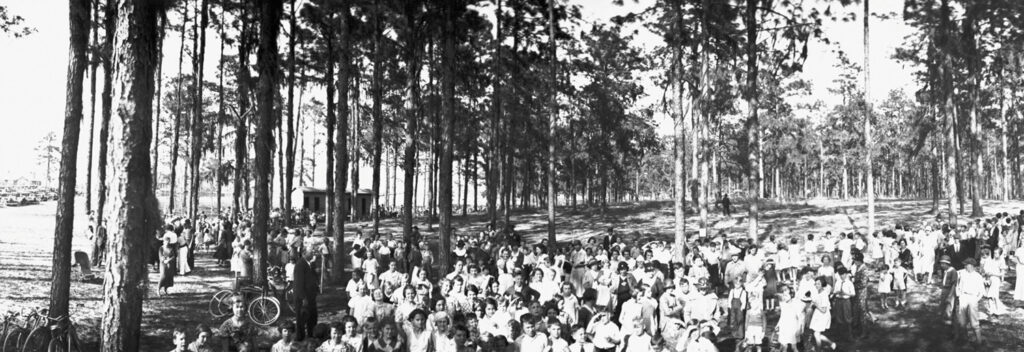

Later, some landowners at Greenfield made money by allowing fishing and renting boats to the anglers. The lake’s pleasant and shady rural surroundings lured generations of picnickers. Local militia companies found it an agreeable place to combine business with pleasure, assembling for drills and target shooting contests. City papers noted several baptism ceremonies at the pond for members of the Front Street Second Advent Church between 1899 and 1906.

Picnics and fishing were natural enough attractions. A perhaps unexpected activity was ice skating. The cold winter of 1893 froze the pond for several days. Some folks ordered ice skates from New York, which arrived in time for them to try out. On Jan. 20, there were an estimated 150 people skating on the ice.

The winter wonderland was not to last much longer. The Wilmington Messenger reported on Jan. 24, 1893, that warm weather “has made the ice melt very rapidly.”

“There was good skating on Saturday, but by Sunday the skaters found it perilous to venture on the ice. A hundred or more were at Turlington’s mill [named for the current owner] and tried the ice, but several broke through, one or two getting in over their heads.”

Over the years, ice skaters had a few more fun days at Greenfield. In 1918, ice as much as four or five inches thick covered the lake for a few days in early January. The Wilmington Morning Star reported the lake froze again in 1940 and ran a photo of two skaters on the front page.

Alligators have long been a feature of Greenfield Lake. Evidently there were no “Do Not Disturb the Alligators” signs back in the 1800s. Several Wilmingtonians caught gators in the lake and made a little money showing them off in the streets or inside saloons.

In 1890, E. Jones caught a 6-foot-8 alligator in his net while fishing in Greenfield Creek below the dam. Jones sold the alligator to S. Van Amringe, president of the Ocean View Railroad (which connected downtown Wilmington to Wrightsville Beach).

The Wilmington Messenger reported “the gator was carried down [to Wrightsville Beach] … and is domiciled in the tank alongside the track at Switchback station.”

Its distance from Wilmington not only kept Greenfield Pond quiet but was also sufficiently isolated for the town to place a smallpox hospital there during an outbreak in 1874.

Beginning in London and Liverpool in the last quarter of 1870, Europe’s smallpox pandemic lasted from 1870 to 1874. A sailor from a schooner at the Wilmington docks collapsed with an illness quickly identified as smallpox. He was staying in a “house of ill repute” on Walnut Street. The sailor died of his illness, and occupants of the house were taken to a small house near Greenfield Pond. They remained in the emergency smallpox hospital under quarantine for 20 days before their release.

Greenfield remained the site of a mill for well over a century and a half. In 1831, James S. Green placed a newspaper ad to say the Greenfield mill was back in operation as a gristmill. A storm in 1837 broke the mill dam, and another storm in 1892 left a 35-foot gap in the dam.

In 1884, owner W. H. Turlington announced the mill had been overhauled, adding “I have had the creek cleaned out for the benefit of persons wishing to carry corn to the mill in boats.” In 1915, the mill advertised that farmers could bring in small amounts of corn for grinding. For payment, the miller took one-eighth of the resulting cornmeal. There was a gristmill running on Greenfield Lake as late as 1923.

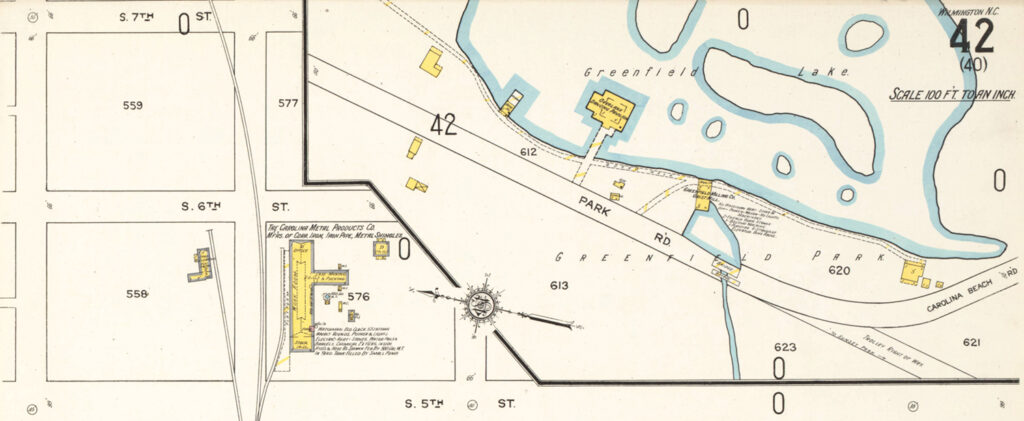

In 1870, the new Greenfield Street marked Wilmington’s southern boundary, a stone’s throw north of Greenfield Pond. By 1915, the city limits reached the northern edges of the water.

For years, city newspapers reported proposals to obtain Greenfield for a city water supply and for a municipal park. A privately owned park opened by the lake shore in 1910. City streetcars provided frequent service to the park.

The opening was marked by several performances of John R. Smith’s Wild West Buffalo Ranch Exposition. A newspaper ad for the show when it was in Washington, North Carolina, promised “horses with human brains. They march, waltz, and cake walk to the merry music of the band. … ‘Arizona Charley’ will every afternoon make his thrilling ‘Roman Racing’ standing on the backs of fiery steeds, besides doing trick and fancy riding.”

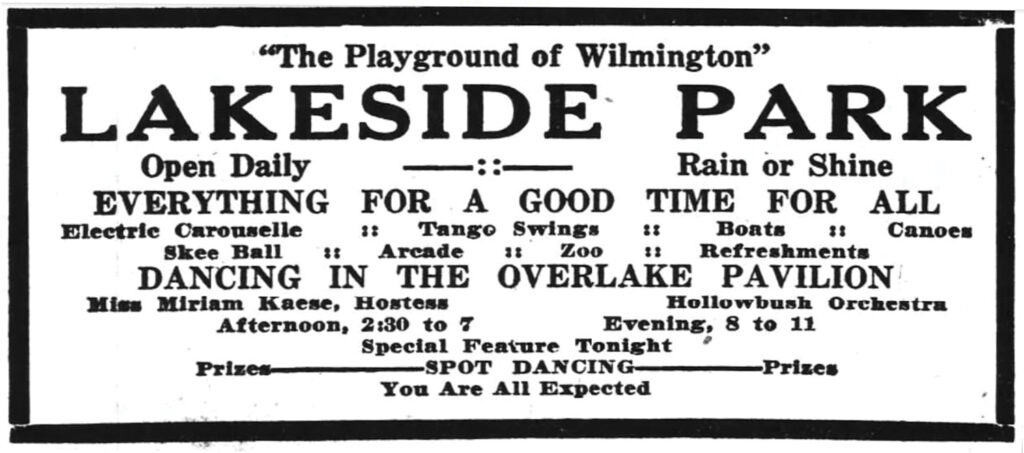

In the original Greenfield Park, the 1915 Sanborn Insurance map showed a boardwalk running along the southern edge of the lake and along the dam, a pier leading to the Overlake Pavilion, which was built over the water, and a small bathhouse nearby.

Unlike today, swimming in the lake was encouraged, and the bathhouse served as a place for swimmers to change their clothes. The pavilion was mainly designed for dancing to live music, but there was also an arcade with various game machines.

In 1915, the Wilmington Morning Star described a rather suspicious-sounding vending machine at Greenfield. “The device has a slot arrangement by which one can drop in a nickel and get a package of chewing gum. It is also stated that one may get two, four, eight, 16, or possibly 20 nickels, if his luck is right.” The county sheriff seized the machine as an illegal gambling device.

By 1919, the park was called Lakeside Park. There was, said the Wilmington Morning Star, “an octagonal shaped building completely enclosed with glass, containing a beautiful Herschell-Spillman $7,500 electric carouselle [sic] with 36 jumping ‘hobby horses,’ two chariots and a magnificent automatic organ.”

Another large new building housed Lakeside Park’s zoo, and yet another housed an “all-steel automatic mechanical shooting gallery.” A new arcade contained several new “skee-ball alley and coin operated machines.”

In 1925, the city bought the lake and surrounding land. The property became Wilmington’s first city park, which today surrounds the 91-acre lake.

In 1931, during the Great Depression, the construction of five miles of paved road around the lake provided badly needed jobs for hundreds of unemployed workers. More work came with the planting of hundreds of azaleas. The bright flowers became a symbol of Wilmington and created a lavish display for the first North Carolina Azalea Festival in 1948.

New attractions came and went. Around 1950, a miniature railroad ride and a carousel were added. Boats took visitors on tours of the lake. The Cypress Queen, a small boat used for lake tours, was supplemented by the Show Boat, a larger vessel resembling a little Mississippi River steamboat. Many Wilmingtonians will remember the park’s children’s zoo. All were closed or removed over time.

A popular and long-running addition, opened in 1961, is the Greenfield Lake Amphitheater. Since 1993, the amphitheater has been the scene of hundreds of performances of the popular Shakespeare on the Green series.

Another recent attraction is the Greenfield Grind Skate Park. A boathouse managed by the Cape Fear River Watch rents paddleboats, kayaks, and canoes.

Greenfield Lake has undergone tremendous change since the 1700s, shifting from agricultural and industrial uses into a center for leisure and relaxation. But some things remain the same. Spanish moss still clings to the cypress trees, which frame beautiful vistas of shadowy woods and the extensive lake.

The timeless allure of nature blends harmoniously with the modern park as Greenfield Park stands on the threshold of its second century.