The Things They Left Us

Remembering World War II Veterans

BY Rona Simmons

Fewer than 120,000 of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II will celebrate Veterans Day this year. The vast majority are now in their 90s, and when they die we will have only books, movies, documentaries, and taped interviews to tell their story.

Words and images, however, can convey only so much. Far better to unfold a letter a soldier wrote to his sweetheart, hold a Bronze Star in your hand, or feel the sharp edge of a piece of shrapnel. These are tangible objects, the things the World War II veterans left us. These are the things that will keep their stories of service and sacrifice alive.

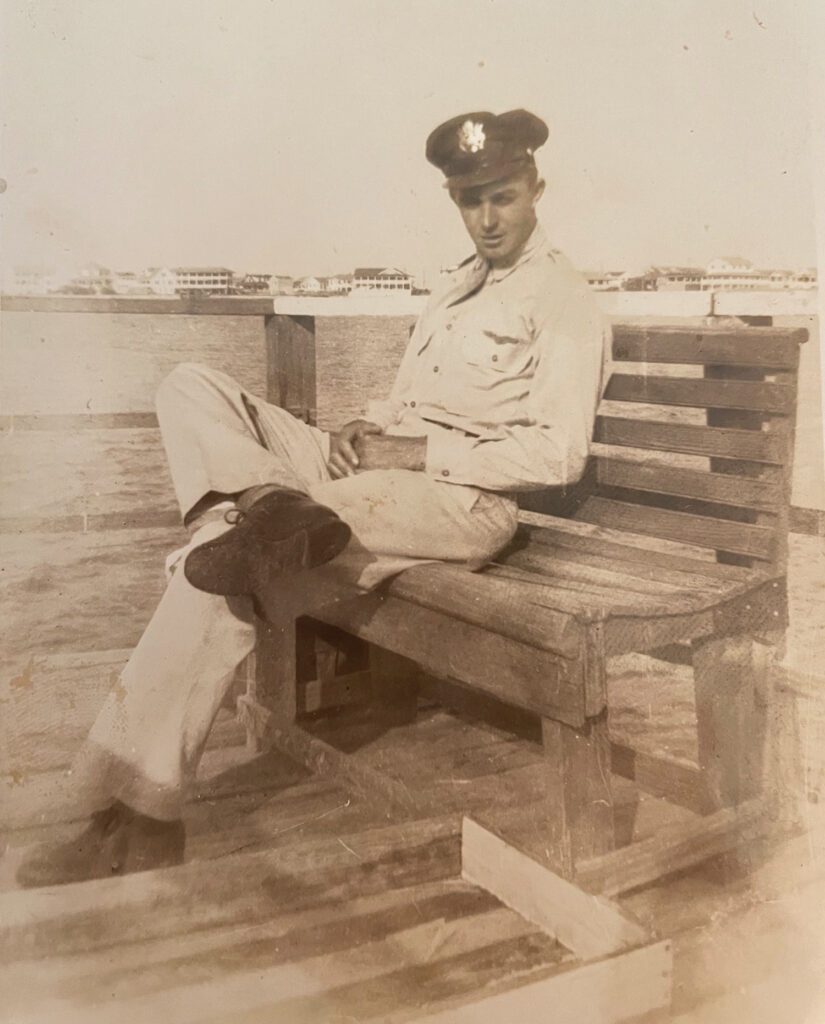

In a glass case inside the Hannah Block Historic USO building is a portrait of Wilmington native George S. Boylan Jr. The stars on his uniform’s epaulettes gleam even in the black and white image.

Photo Courtesy Rona Simmons

Other artifacts of Lt. Gen. Boylan’s distinguished 35-year military career accompany the portrait. The dominant feature is a large, well-worn footlocker. Its metal clasp and reinforced corners were meant to withstand the rigors of travel. And travel the footlocker did, from his days as a young cadet with the Army Air Corps to his station at Hardwick, England, where he flew B-24 bombers and later commanded the Eighth Air Force’s 329th Bombardment Squadron.

It traveled to Maxwell Air Base in Alabama, Hickam Air Base in Hawaii, and dozens of other locations around the world. Finally, like its owner, the footlocker came home to Wilmington.

Muffy Boylan, George’s daughter, remembers it being ever present.

“But the Wilmington address stamped on its lid always reminded us of home,” she says.

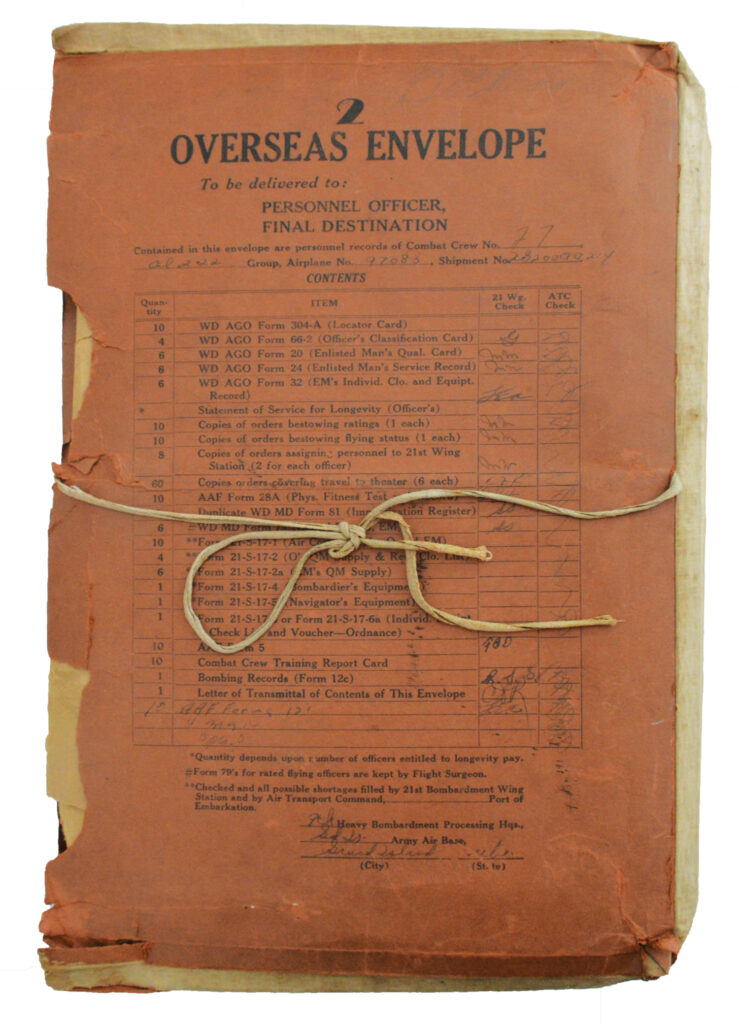

Or take the ribbon-tied, overseas envelope that Harry Bethea, another Wilmingtonian, Air Force officer, and B-17 bomber pilot, left behind.

The folder, now in the UNCW Library archives, is faded and torn; its dog-eared contents bear deep creases. The documents offer insight into the long, bureaucracy-laden period between enlisting and deploying overseas. The forms list the crew’s names and serial numbers, their belongings (from trenching shovels to oxygen masks), their aircraft number, and their departure date.

At each stop, from Kansas to Nebraska to New Hampshire and finally to RAF Thorpe Abbotts at Diss, England, Bethea would show the requisite form, wait for it to be stamped or stapled to another, then refold and return the papers to the envelope.

“Like many veterans, my father died without speaking of his experience during the war,” says Harry Bethea Jr. “But by leafing through these pages I found a way to connect with him and piece together where he served and what he did.”

Ginger Davis also has mementos of the war — a collection of coins from her grandfather, U.S. Army technician fifth grade Thomas Davis.

She remembers hearing stories of the war while sitting at his knee in Bailey, North Carolina. The eager-to-learn 8-year-old once pulled a dark and discolored coin from the stack. Seeing that it bore symbols of the Third Reich, she asked, “Did you really meet a Nazi?”

He said he had not and changed the subject. Although he had been in the thick of the action at Remagen, Germany, and the Ardennes in France, the tales Davis preferred to tell were of faraway places, different cultures, and long-ago times.

“There’s no doubt he instilled in me a love of history and seeing the world,” says Ginger, who became a history professor, traveled extensively, and settled in Wilmington to become executive director of the Lower Cape Fear Historical Society.

Families of WWII veterans might have a box of yellowed photos or a uniform hanging at the back of the closet. This year, take them out, dust them off, and rediscover a story to remember, relish, and share.