The Splendor of Fort Caswell

An instrument of peace and inspiration

BY Pat Bradford

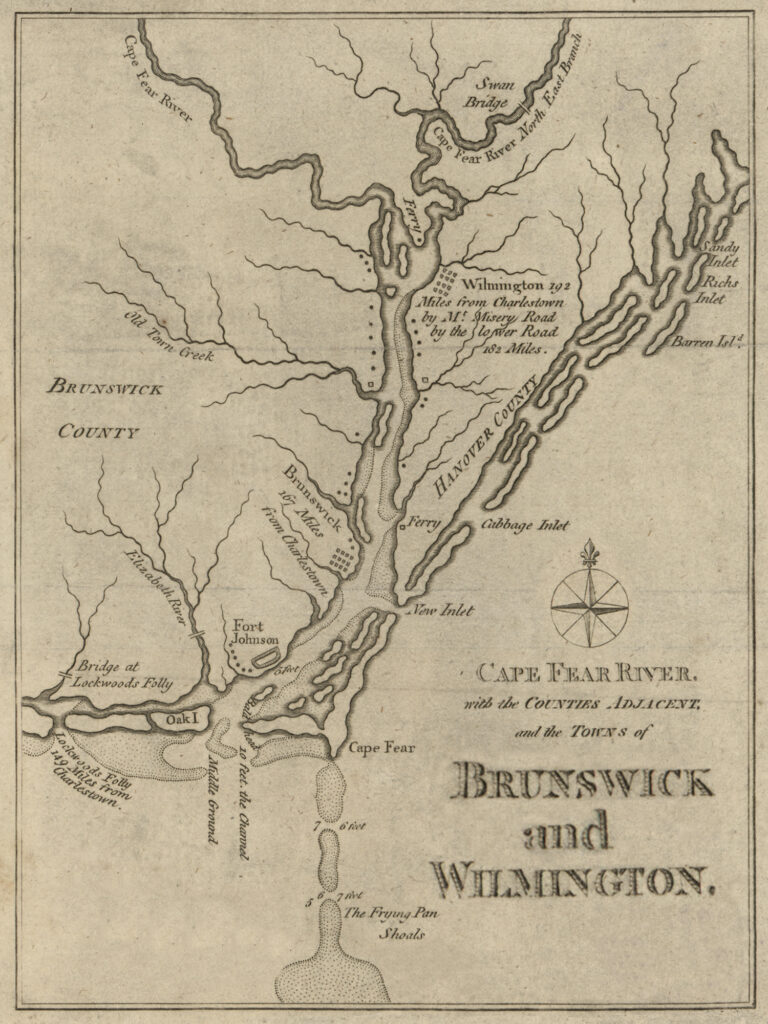

Eastern North Carolina is rich in American history and historical sites. One within an hour’s drive of Wilmington is lesser-known Fort Caswell. It lies on the eastern end of Oak Island at the convergence of the Cape Fear River and Atlantic Ocean, between Southport on the Brunswick County mainland and 12,000-acre Bald Head Island.

Now a restricted-access private retreat and conference center, the site was placed on the National Registry of Historic Places in 2013.

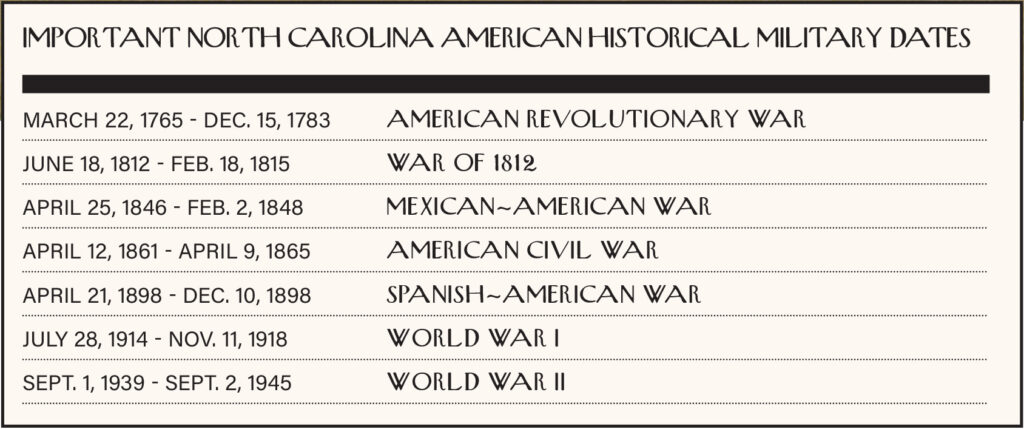

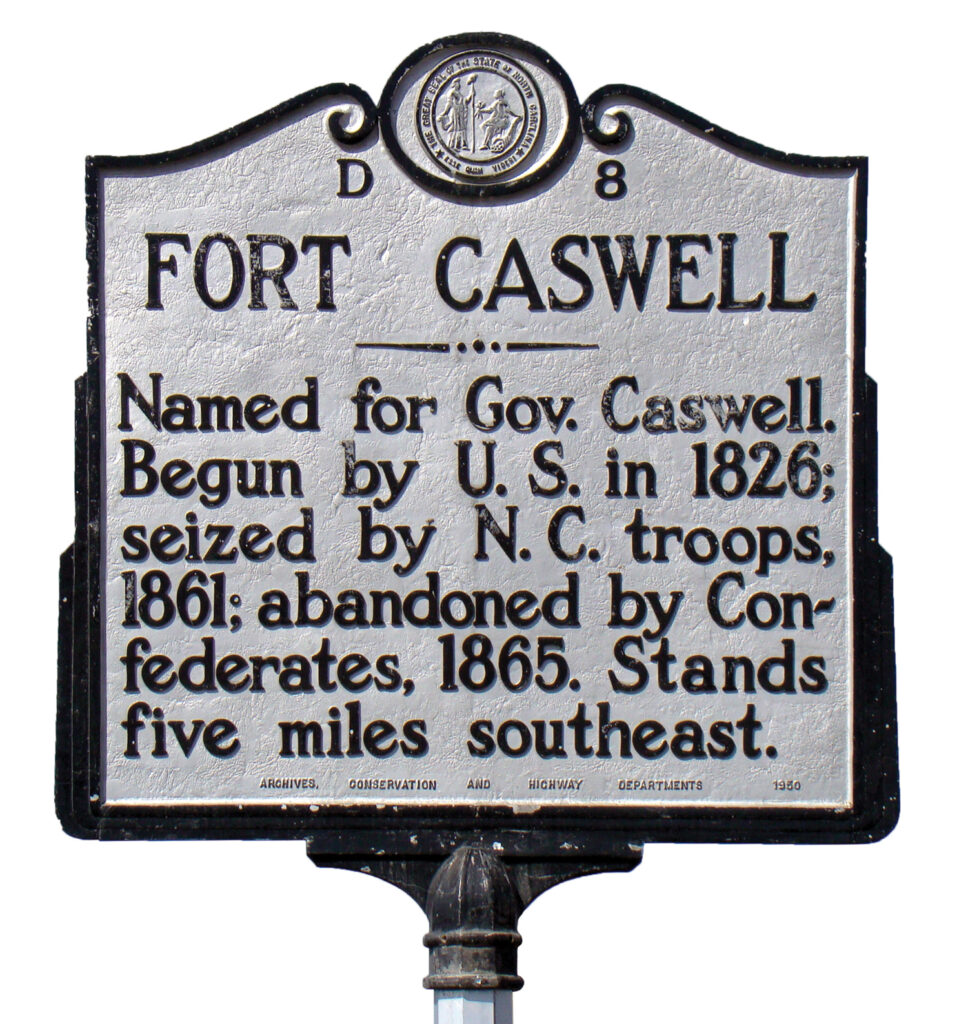

Beginning with congressional approval of funds on March 2, 1825, the U.S. government purchased the 2,800 acres on the east end of Oak Island for the construction of a military reservation. The barrier island installation would be home to a variety of American armed forces for 20 years.

The fort was named for Richard Caswell, the first governor of North Carolina.

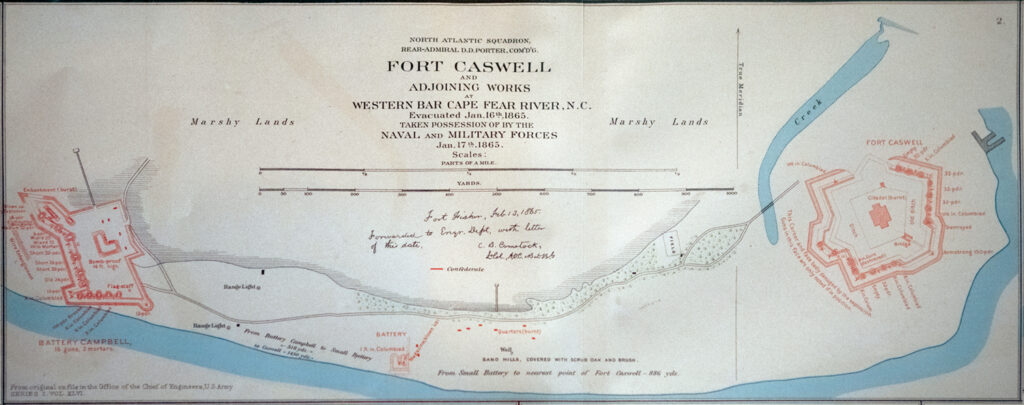

Taking nine years, the pentagon-shaped original fortification was built with brick and mortar beginning in 1827 at a cost of $473,000. It had large earthworks. Inside the structure’s walls was a citadel or defensive barracks. The construction was earth, brick and concrete (this included sand and shell material, visible today.) The complete fortress had armament for 61 channel-bearing guns, with a garrison of approximately 400 soldiers.

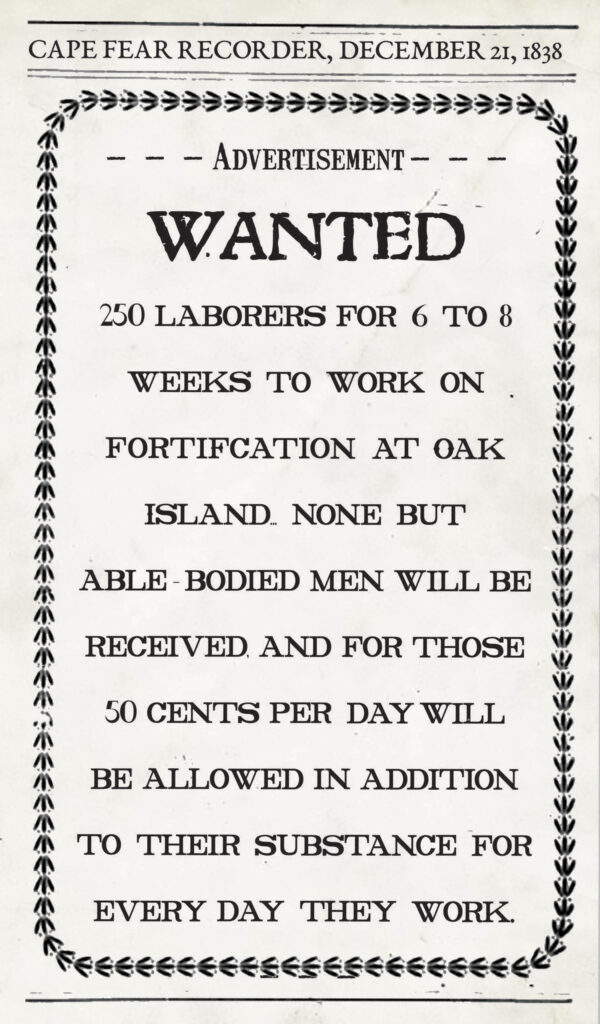

In an 1838 newspaper advertisement, 250 laborers were sought to work for 50 cents per day in addition to their substance for every day they worked. Another newspaper advertisement in 1846 offered able-bodied laborers $18 a month or 75 cents a day without rations. The workers and building materials had to be transported to the island by boat.

Guarding the mouth of the Cape Fear River, the military installation joined British-built Fort Johnson (constructed in 1749 to defend against the French and Spanish) as a network of defense downriver from Wilmington, the largest city in North Carolina at the time.

Offshore, past small coastal islands including Battery, Shell, Striking, Zeke’s, Middle and Bluff islands and the larger Smith Island (now known as Bald Head Island), lies the natural protection of the treacherous 28-mile-long Frying Pan Shoals, a part of the Graveyard of the Atlantic. The entrance to the Cape Fear River itself, navigable at the time all the way to Fayetteville, is protected by a natural and shifting bar.

Fort Holmes and Fort Hendrick batteries were built on Smith Island. Fort Anderson was built at Brunswick Town. Many other batteries and forts were built along the Cape Fear River, once known as River Jordan.

Fortified Fort Caswell, surrounded by a dry and wet moat, was never destroyed by a direct attack, nor were lives lost in battle there. It was seized two times in early 1861, once by the Cape Fear Minute Men and a second time by the Wilmington Light Infantry.

When North Carolina seceded May 20, 1861, the fort became a Confederate Army post that, along with Fort Fisher, built in 1861 on Federal Point in southern New Hanover County, created a highly effective defense system.

After failed Union Army military action, including six plans to capture Fort Caswell, the Union focused its attention to taking Fort Fisher.

Two days after the Jan. 15, 1865, capture of Fort Fisher, Fort Caswell was abandoned, but not before the retreating Confederate soldiers spiked the cannons, burned the barracks, and ignited ammunition magazines containing 100,000 pounds of gunpowder.

The explosion broke windows in Smithville — now the town of Southport — and was reportedly heard and felt as far away as Fayetteville. It destroyed the southeast face of the fort and damaged the western face.

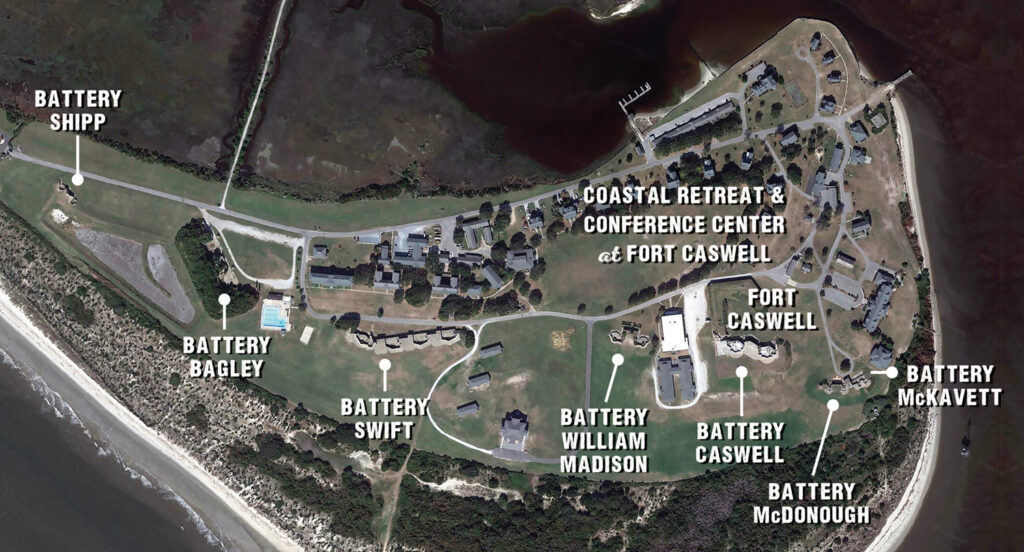

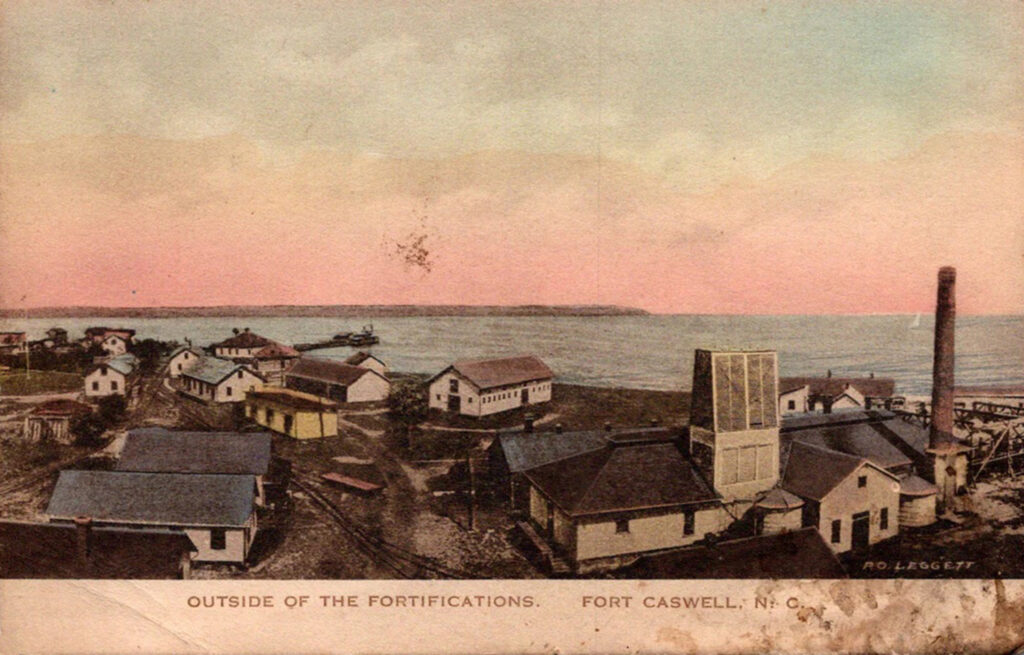

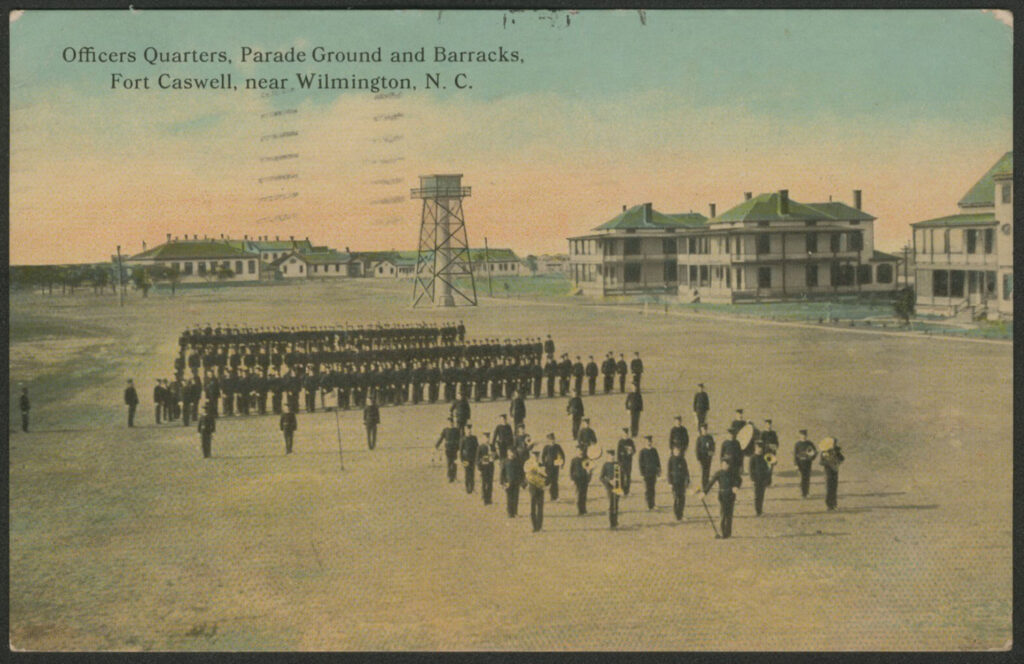

Following the Civil War, in the 1890s to early 1900s the U.S. Army built a full military installation on the site including coastal artillery batteries as well as a 6,612-foot seawall. At this point, a shift in the design happened in the new fortifications, creating a series of batteries spread along the coast. During the early 20th century, houses, barracks, storehouses, mess halls, a schoolhouse, a hospital, guardhouse and facilities for a blacksmith, carpenter and plumber were erected in addition to a headquarters, identical officers’ quarters, and stable. Many of the buildings and structures were built by the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps in a Colonial Revival, Queen Anne style.

The fort was occupied by troops in both the Spanish-American War and World War I. In World War II the fort and the Fort Caswell rifle range served as a U.S. Army training ground facility.

It moved into private ownership after being sold in 1925 and was operated as a resort. Gun emplacements were converted into swimming pools supplied by hot mineral water (sulfur) from two artesian wells.

The resort was not prosperous.

In 1941, the U.S. Navy purchased the 248.8 acres inside the seawall for $75,000 from the Caswell-Carolina Corp. for use as an offshore patrol and anti-submarine base during World War II.

The last sale was in 1949, a $86,000 purchase from government surplus by the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina.

It is now operated by the North Carolina Baptist Association as a Christian retreat.

Summers are reserved for Baptist youth camps. Throughout the rest of the year the facilities are open to groups from other Christian denominations, as well as schools, universities, and nonprofits. There are numerous conference and retreat opportunities.

Guarded by a manned gate, public drive-throughs are allowed on particular days and times but the property is not open to the general public at all times.

Today the fortifications are visible and accessible. With the Atlantic and a sandy beach, Bald Head Island gleaming in the distance, and bounded by the Cape Fear River, the property benefits from almost constant sea breezes.

There are large live oak trees, some of significant proportions.

Restored officers quarters and other buildings surround what was the military parade ground, which remains a green open space lined with live oak trees. The tower base of the troop viewing stand still stands in silent witness to the past.

Still 250 acres, Fort Caswell has a lot of open green space and ruins to explore.

Beside historic buildings of brick and mortar, raised wood-frame buildings and cottages match in architectural style and paint colors. Along with multi-storied lodging and a single-story motel are nonresidential buildings including classrooms, an auditorium, children’s buildings, a conference center, a PX, a cafeteria, and a chapel and chapel annex. Other amenities include a pool, tennis and volleyball courts, a gym, a mini golf course, and a fishing pier.

Every Christmas season the grounds are lit and embellished, making it a magical time for a retreat. In 2023, the general public can drive through the Light of the World celebration Dec. 1-22 from 6-8 p.m.

Although just minutes off the mainland and modern civilization, this is a place of absolute peace, tranquility and inspiration.

The forward of Fort Caswell in War and Peace by Ethel Hearing and Carolee Williams quotes longtime North Carolina Baptist Association director Richard Holbrook. “Fort Caswell was built as a defense against war but it is now an instrument of peace.”

Fort Caswell Rifle Range

The 184-foot-long Fort Caswell Rifle Range is located in the town of Caswell Beach. It is on private property and protected as part of the historic district.

This non-contiguous part of the fort lies two miles northwest of Fort Caswell. It defended military positions during the Civil War, served as a U.S. Army training ground in World War I, and was a communications base during World War II.

It was used for small arms training for soldiers in January 1919.

The rifle range is made up of three sections of concrete walls; some of the construction is below grade, sloping north to south. It is open in various widths, although some were covered for storage. The thickness of the concrete ranges between 8 inches to 1 foot.

This site was sold as surplus after World War II. It was left untended until restoration began in 2012. To protect and preserve the site, the friends of Fort Caswell Rifle Range created a nonprofit in 2015 with the town of Caswell Beach and Caswell Dunes Homeowners Association.