The Sea

A mix of past and present seascapes inspires Andre Snyman to channel mood and rhythm through art

BY Emory Rakestraw

“There are times, they occur with increasing frequency nowadays, when I seem to know nothing, when everything I know seems to have fallen out of my mind like a shower of rain, and I am gripped for a moment in paralyzed dismay, waiting for it all to come back with no certainty that it will.”

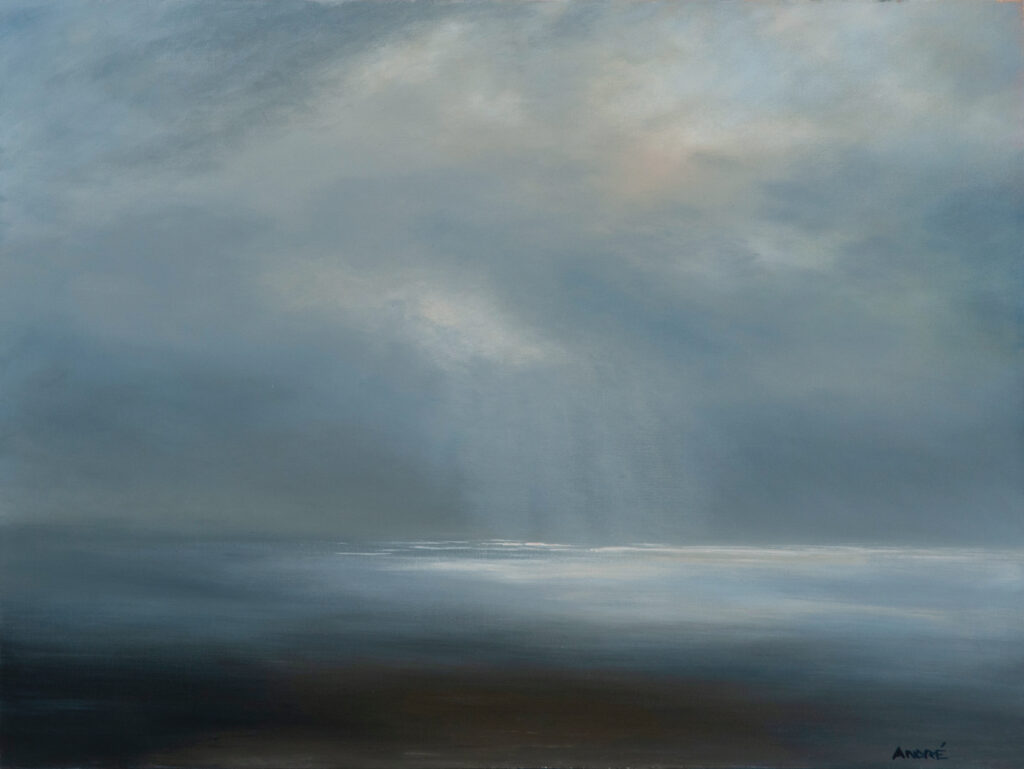

On an Instagram post of his work There Are Times, artist Andre Snyman included a screenshot of the above quote from John Banville’s novel The Sea. In the painting, the foreboding gray landscape dominates, but there is hope on the yellow horizon as sunbeams push through the clouds.

In the novel, retired art historian Max Morden returns to the seaside town of Ballyless after the death of his wife. The landscape holds memories of childhood, a formative summer holiday, and reflection of the past and present.

Like the protagonist, Snyman has memories of childhood in a seaside town. Mossel Bay, South Africa, serves as a meditation when it comes time to paint his overflowing yet muted seascapes where water and sky comingle for dominance on the canvas.

“I like the seascapes because it reminds me of home in South Africa. I grew up in this small town made up of long beaches and I spent my whole life there until I was 27,” says Snyman. “When I first started [painting] I was into surf art and eventually realized I really enjoyed painting skylines and scenes. Messing with different paints and going from oil to acrylic brought about these things that kind of came out of accident.”

An avid surfer, Snyman says with a chuckle that his hometown is where you see great white sharks jumping out of the water on National Geographic. Even lingering threats beneath the surface didn’t prevent him from practicing the sport most of his childhood and adulthood. Today, his detailed wave paintings like Breaking Point and Seaglass are images inspired by hours spent surfing Mossel Bay, Nicaragua, California, and now Wrightsville Beach.

Much like how The Sea grapples with the way the mind interprets memories, Snyman is exploring his own interpretations of scenes that hold a subjective meaning to artist and viewer. His paintings often depict foggy atmospheres where a body of water acts as a mirror to the sky. Even the moodiest sprawling scenes allow precedence of time over place, like Between Earth and Sky inspired by the Banville quote, “At the seaside all is narrow horizontals, the world reduced to a few long straight lines pressed between earth and sky.”

“I grew up by the ocean and have spent a lot of time sitting on the beach and staring at the waves or tides. I’ve always enjoyed it and in a sense was trying to replicate that,” he says. “To me, it’s like a mood. I think eventually my paintings will get more abstract. Mark Rothko played on that whole notion of color influencing mood, the concept of a piece of art that looks simple but when you really look at it and think about it, it’s not.”

While Rothko is best known for his use of vivid colors, Snyman takes the opposite route, utilizing a neutral palette that he finds more challenging than traditional sunset tones. He mixes mostly grays, blues, and what he calls a “secret sauce” for complex shades. Ironically, his personal favorite, Whispering Waves, possesses splashes of pastel pink and warm golds one might see after sunset or just before sunrise.

It’s not always sea and sky, though. Heaven Is The Place We Know was a commissioned work that takes a more landscape style, with green-drenched cliffs and radiant hues of blue inspired by his time in Los Angeles and nearby Palos Verdes Cove. It wasn’t just the landscape where he found assistance, but also from a former art mentor who encouraged his specific seascape style, leading to a 2018 solo show, Ephemeral.

While today his home studio is mostly filled with framed works in a similar likeness, a piece-in-progress of a non-conspicuous surfer riding a wave rests on the easel.

“I’m totally inspired by the landscape here in Wrightsville Beach, I have so many pictures of Wrightsville Beach it’s ridiculous,” he says. “If I can’t make it to the beach, I’m taking screenshots of the surf cam.”

Snyman has also taken an interest in ways to give back to the community.

“I did a surf painting of [local surfer and skateboarder] Jacob Venditti and donated it to him for the Live Fearlessly Foundation, a local nonprofit that raises awareness and funds for cystic fibrosis,” he says.

Snyman also donated a painting to The Harrelson Center for its Day in the Country fundraiser.

When Snyman isn’t surfing or including literary quotes alongside his paintings, he’s listening to music. So You Think You Can Tell, derived from Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here, takes an abstract focus wherein water acts like a memory — imaginative in the foreground yet dark and unwavering as it inches closer to the edge of the canvas — or in a philosophical sense, the present.

Music can be a source of recollection. Snyman’s paintings resemble this with their own rhythm and feel, yet ambiguous atmospheres still land on a place of familiarity.

“When I listen to something while I work, in a way that influences the painting or the way I feel about the painting,” he says. “The ocean has such a soft peacefulness. I try to catch that moment. In nature, everything is fleeting, and I want to capture that beauty before it’s gone.”

In The Sea, the narrator describes memories of his late wife in terms of “fraying, bits of pigments, flakes of gold leaf.” Snyman’s visits home awaken distant memories that live on in his current work, be it childhood or venturing from West to East Coast and embracing new scenery with the common thread of sky and water.

Even if he later takes a more abstract route, it’s safe to say each work will continue to possess the quiet, internal exhale one feels when resting beside the ocean. To quote Banville, “Although it was autumn and not summer the dark-gold sunlight and the inky shadows, long and slender in the shape of felled cypresses, were the same, and there was the same sense of everything drenched and jewelled and the same ultramarine glitter on the sea. I felt inexplicably lightened; it was as if the evening, in all the drench and drip of its fallacious pathos, had temporarily taken over from me the burden of grieving.”