The Osprey

By any name, the seahawk is a magnificent bird

BY Elyse Kiel

The wildlife of Wilmington is truly a sight to behold. Look down and see scattering green anoles and the flashing scales of a rattlesnake. Look out to sea and witness dolphins playing in the waves and stingrays flapping in the tide. Look up and spot squawking seagulls and watch the city’s most magnificent bird: the osprey.

Ospreys are known by another name in Wilmington: the seahawk. These beloved birds are featured throughout the city through art, literature, and in our history.

The most well-known example is the seahawk statues across the University of North Carolina Wilmington campus. Created by Wilmington native and metal sculptor Dumay Gorham, the statues represent a student’s journey to graduation, from a fledgling flapping its wings at the edge of its nest to the great soaring adult bird that is often the location for graduation photos.

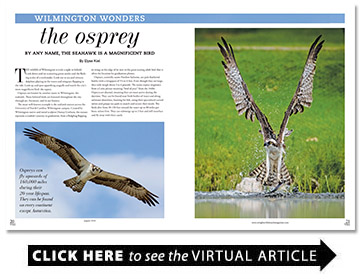

Ospreys, scientific name Pandion haliaetus, are pale-feathered hawks with a wingspan of 5½ to 6 feet. Even though they are large, they only weigh about 3 to 4 pounds. The name osprey originates from a Latin phrase meaning “bird of prey” from the 1460s. Ospreys are diurnal, meaning they are most active during the daytime. They can be found near fresh bodies of water and along saltwater shorelines, hunting for fish, using their specialized curved talons and grippy toe pads to snatch and secure their meals. The birds dive from 30-130 feet toward the water up to 80 miles per hour, talons first. They can submerge up to 3 feet and still resurface and fly away with their catch.

In Wilmington, ospreys feed on flounder, mullet, and other kinds of fish in the ocean and bodies of fresh water. Their diet consists almost entirely of fish, only branching out to small lizards and other birds when food is scarce.

Ospreys are migratory, often breeding in the north and flying south in the winter after nesting season and the waters start to chill. They can fly upwards of 160,000 miles during their 20-year lifespan. They can be found on every continent except Antarctica, so keep your eyes peeled whenever you are near a body of water for the tell-tale pale feathers and slow, impressive wing beats.

Ospreys can fly upwards of 160,000 miles during their 20-year lifespan. They can be found on every continent except Antarctica.

Ospreys mate for life most of the time. If they are unsuccessful in producing eggs during their first breeding season, they may separate and find a better suited partner. Their mating habits include the male performing an aerial dance of sorts. The pair will fly together, circling one another. The male will then fly high above the nest, often carrying nesting material or a fish, then dive down into the nesting area carrying his prize.

A pair will return to the same nesting site for years. With continuous use, their nests can sometimes end up 10-13 feet deep. Nests are made of various items, including large sticks, seaweed, and bark.

A breeding pair will produce one to four 2-3-inch eggs per year. Incubation typically takes about 38 days. The hatchlings stay in the nest for about 50 to 55 days before taking their first flight.

Even though ospreys have rebounded from endangered status in the 1950s and ’60s due to DDT, threats remain. Issues that can impact a healthy osprey population in Wilmington include overfishing of the Cape Fear River and shorelines, which can lead to difficulty finding food; the use of pesticides that cause eggshell thinning, resulting in improper incubation; and changes in coastlines and riverways that destroy their nests.

Some local spots to catch a glimpse of ospreys include Greenfield Lake Park, Airlie Gardens, Carolina Beach State Park, and along the Cape Fear River.

Ospreys are not only a mascot for UNCW, but also an excellent barometer of environmental health. These magnificent birds are bioindicators of the health of our local waterways. The return and reproduction of ospreys allows us to better understand what our environment is lacking or what is successful.

Ospreys are a beautiful part of Wilmington, and we can keep them coming back every year by creating more spaces for them to nest, maintaining a healthy and balanced fish population, and cleaning our environment from harmful materials that can end up in their nests or their diet, such as fishing nets, plastic bottles, and scattered garbage.