The Long Journey Home: Air Force Major Ronnie Brown

BY Robert Rehder

Wilmington lost 20 sons in the Vietnam War. They were Marines soldiers sailors and airmen. They were athletes musicians lifeguards and fishermen. They were much-loved husbands sons fathers and brothers.

Many went into military service after graduating from New Hanover High School. Some like Ronnie Brown went on to college. To those who knew them they might have seemed just ordinary men and yet through extraordinary courage they gave their lives.

Air Force Major Ronnie Brown’s story is quite different from the others. His family suffered perhaps the worst tragedy of all when for decades during and after the war he was Missing in Action (MIA).

On a warm late-summer day in 1954 C.L. Mckenzie Jerry Partrick and Ronnie Brown laughed and joked as they walked down Salisbury Street at Wrightsville Beach toward a booming surf just south of Johnnie Mercer’s Pier. It was before the arrival of surfboards and the three were going bodysurfing in the clear ocean waters. There was a hint of fall in the air with a light offshore breeze kicking up a gentle swell. The view was stunning with crystal white dunes towering waves and a sparkling blue-green sea. The three young Wrightsville Beach lifeguards had hardly a care in the world. Each had recently graduated from New Hanover High School and Brown would soon be a freshman at his future alma mater UNC at Chapel Hill.

“Our 1954 New Hanover yearbook had his name as Ronnie Brown and some called him that but to his close friends and he had many he was just “Bubba ” says C.L. Mckenzie. “If there was ever a man who loved Wrightsville Beach — swimming bodysurfing and the ocean — it was Bubba.”

Dr. Jerry Partrick remembered Brown as a dedicated lifeguard and loyal friend.

“I lived at Summer’s Rest and Bubba lived on Harbor Island so we grew up close friends and lifeguards together ” says Partrick. “We were both at Carolina but then I went into the Army and Bubba went to flight school in the Air Force.”

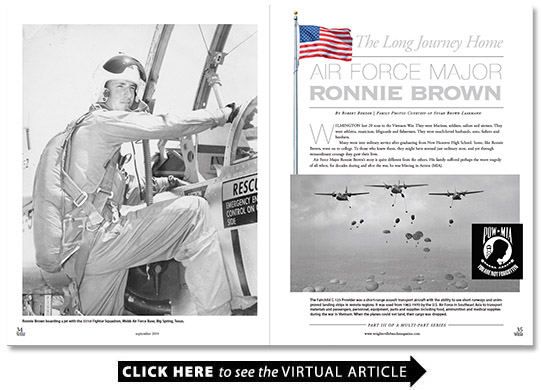

Wilbur Ronald Brown was born in Wilmington on July 22 1936 to Wilbur and Lillie Mae Brown and spent his boyhood years at their family home on Harbor Island. The 1954 New Hanover High School yearbook reveals he was in the English Government and Spanish clubs and in ROTC with the Sergeant’s Club. After graduation he entered UNC at Chapel Hill where he graduated in 1958 and soon after went to Air Force flight school. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1960 at Greenville Air Force Base in Greenville Mississippi and trained at the 331st Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Webb Air Force Base in Big Spring Texas.

He married Bette Cannon Woodbury from Wilmington on March 22 1960 and they had two daughters Kathy and Susan.

Always the consummate pilot Ronnie Brown loved flying and he loved teaching young pilots to fly. Brown was the kind of flight officer who always did more than what was expected of him.

“In 1966 I was in the Navy and Ronnie was on active duty as an Air Force instructor pilot ” says Max Woodbury Brown’s close friend and former brother-in-law. “Even though the Vietnam War was at a peak it was just his nature to volunteer for combat duty there. He was always fun with a friendly outgoing spirit and I cannot tell you how many wonderful times we had at the beach.”

Brown reported for duty Jan. 28 1966 at the Air Force 315th Air Commando Group at Da Nang Air Base South Vietnam.

He had only been in Vietnam for seven days when on Feb. 3 he received orders as lead pilot of a Fairchild Provider C-123 aircraft tail number 55-4537 for an airlift supply mission from Da Nang to the beleaguered Khe Sanh Marine Base in Quang Tri Province. The Provider was an Air Force military transport aircraft used for supply medical evacuation and reconnaissance. With him that day were Col. James L. Carter flight commander; Chief Master Sgt. Edward M. Parsley loadmaster; and Chief Master Sgt. Therman M. Waller flight mechanic. The aircraft departed Da Nang that afternoon on a multiple-stop supply route that included the Khe Sanh Marine Base and the Dong Ha Combat Base both in Quang Tri Province.

Having completed the supply mission the transport then flew southwest along the border of Laos. It was there radio contact was lost. When contact could not be re-established search-and-rescue efforts began.

The area where the Provider was believed to have gone down was initially searched by air but no trace of the aircraft or its crew was sighted in the extremely dense mountainous jungle. Searches were suspended on Feb. 10 1966. The C-123’s last known location was described as being on the north side of a rugged mountain ridge with a long narrow jungle-covered valley northeast of Khe Sanh.

Had the transport crashed? Had the crew perished? Had they parachuted to safety? Were they captured and now prisoners of war? Those questions would remain unanswered for some 37 years because the powers who controlled the battlefields of Vietnam and Laos would not allow American teams to search on the ground for the missing soldiers.

The crew of Provider 55-4537 joined some 1 800 American souls lost and listed as Missing in Action in Southeast Asia in 1966.

In Wilmington Maj. Brown’s family had received remarkably little information from the Air Force and could only hope that he was still alive.

The A Shau Valley lies in Thura Thien province which abuts Quang Tri Province to the north Da Nang to the south and the border of Laos to the west. Covered with tall jungle grass and flanked by two densely forested mountain ridges it runs north and south for some 25 miles. The A Shau Valley was thought to contain an estimated 20 000 Communist troops and a massive store of war supplies. Its underground bunkers and tunnels were defended by powerful 37 mm anti-aircraft cannons. The North Vietnamese Army (NVA) used the steep mountainous terrain surrounding the valley for cover to launch battles against every major allied position. Its location and description roughly corresponds with the description of the suspected crash site of Maj. Brown’s aircraft.

But why would a supply plane fly in such an area?

To monitor the suspected buildup of enemy forces in the A Shau Valley and the bisecting NVA supply route from Laos known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail flight units such as Maj. Brown’s 315th Air Commando Group routinely conducted reconnaissance flights there. Their mission would have been to observe and report the coordinates of NVA troops and anti-aircraft emplacements. When those missions were successful airstrikes could then be launched against enemy positions prior to the advance of infantry forces saving lives on the ground.

The C-123 having completed its airlift support task was most likely sent on such a reconnaissance mission.

Maj. Ronnie Brown was reported MIA on February 3 1966. He remained in the status of MIA for eight years. It was not until May 30 1974 that the Air Force changed Maj. Brown’s status from Missing to Presumed Killed in Action (KIA) but his remains were still not found or repatriated.

The tortuous uncertainty for the Brown family remained without closure for another 26 years until 2000 when joint U.S. and Vietnamese POW/MIA Accounting Command teams were finally able to investigate possible crash sites of U.S. aircraft in Vietnam Laos and Cambodia. One of those sites was the remote area suspected of holding the missing plane. That specific site was never revealed to the Brown family by the Air Force nor were the circumstances surrounding Maj. Brown’s final flight.

In time the site which was probably in the A Shau Valley but was never revealed produced wreckage consistent with that of a C-123 aircraft. Later the aircraft’s tail number 55-4537 was recovered and established as Maj. Brown’s plane. Consequently on May 19 2003 the remains of the crew of Provider 55-4537 were recovered and arrived at the forensic anthropology laboratory at Hawaii’s Hickam Air Force Base.

It was not until Jan. 23 2009 that Maj. Ronnie Brown was positively identified.

On Aug. 28 2009 52 years after he disappeared his remains were released to his family and interred with honors in Arlington National Cemetery along with his crew of Provider 55-4537. They are interred together.

In Vietnam American pilots and air crews were constantly called upon to fly under the most dangerous situations imaginable — sometimes around the clock. At terrible risk and through sheer courage they flew low-level reconnaissance bringing reinforcements in casualties out attack strafing bombing and supply runs always under the threat of enemy fire. They risked their lives so that allied forces on the ground below could live.

A total 2 197 fixed-wing aircraft were lost in the war.

As of Dec. 21 2018 according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency there are still 1 592 U.S. military and civilian personnel unaccounted for in the Vietnam War many of them pilots and air crew.

U.S. Air Force Maj. Wilbur R. “Ronnie” Brown an American patriot who gave his life so that others could live can be found on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall at Panel 4E Line 134.

This is Part III of a multi-part series. For Part I: Lloyd “Whit” Whitfield see the May 2019 issue of WBM. For Part II: Dayton “Wayne” Lanier see the July 2019 issue of WBM.

Writer Robert Rehder is a Navy veteran who served during the Vietnam War. His father was a WWII Merchant Marine deck officer who sailed in three war theaters. His grandfather enlisting at age 44 was a WWII Army finance officer who served in France. His brother was an Army 82nd Airborne artillery lieutenant in Vietnam. The Rehders have two sons who are both United States Marines.

Fairchild C123 Provider Facts

The Fairchild C-123 provider was a short-range assault transport aircraft with the ability to use short runways and unimproved landing strips in remote regions and was used from 1962-1970 by the U.S. Air Force in Southeast Asia to transport materials and passengers personnel equipment parts and supplies including food ammunition and medical supplies during the war in Vietnam. When the planes could not land their cargo was dropped.

“Most routine supply missions were short less than an hour long but the sixty planes were each flying about five sorties a day. The types of cargo the planes carried mirrored the nature of the Vietnamese war and society. Besides such military items as ammunition loaded fuel bladders aircraft parts and vehicles the aircraft moved Vietnamese war refugees coal live pigs cows chickens ducks and peacocks rice wine mail and whatever else was needed and could fit into the holds ” states The War in South Vietnam The Years of the Offensive 1965-1968 by John Schlight quoting the Gravel Pentagon Papers 111 pp 402 446.

C-123 Providers were featured in the following films:Con Air Air America Outbreak Operation Dumbo Drop American Made.

A number of C-123s were configured as VIP transports including that of the senior military commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam 1964-1972 — Gen. William C. Westmoreland’s “The White Whale ” also known as Westmoreland’s Jungle Taxi.

The C-123 Provider was used by theU.S. Coast Guardforsearch-and-rescuemissions.

President John F. Kennedy’s Ford Lincolnlimousinefor his November 1963 Texas tour was transported to San Antonio by a C-123 piloted by the 76th Air Transport Squadron.

During the Vietnam War the U.S. Air Force also used C-123 aircraft in “Operation Ranch Hand” to spray herbicidal Agent Orange to clear jungles that provided enemy cover.