The Legendary Orange Street Tennis Court

Dr. Hubert Eaton and Lenny Simpson

BY Pat Bradford

Seventy years ago, a small boy named Lendward Simpson Jr. lived with his mother and father Lendward Sr. at 1417 Ann Street, in Wilmington.

Around the corner at 14th and Orange streets lived Dr. Hubert A. Eaton Sr., whose medical practice was on the northside on Red Cross Street.

The Eatons and Simpsons were family friends. Eaton was a successful doctor and an outstanding tennis player (elected to the North Carolina Tennis Hall of Fame in 1984).

His house, built in 1929, sat on almost five acres and boasted an Olympic-size backyard swimming pool, clay tennis court and a three-car garage.

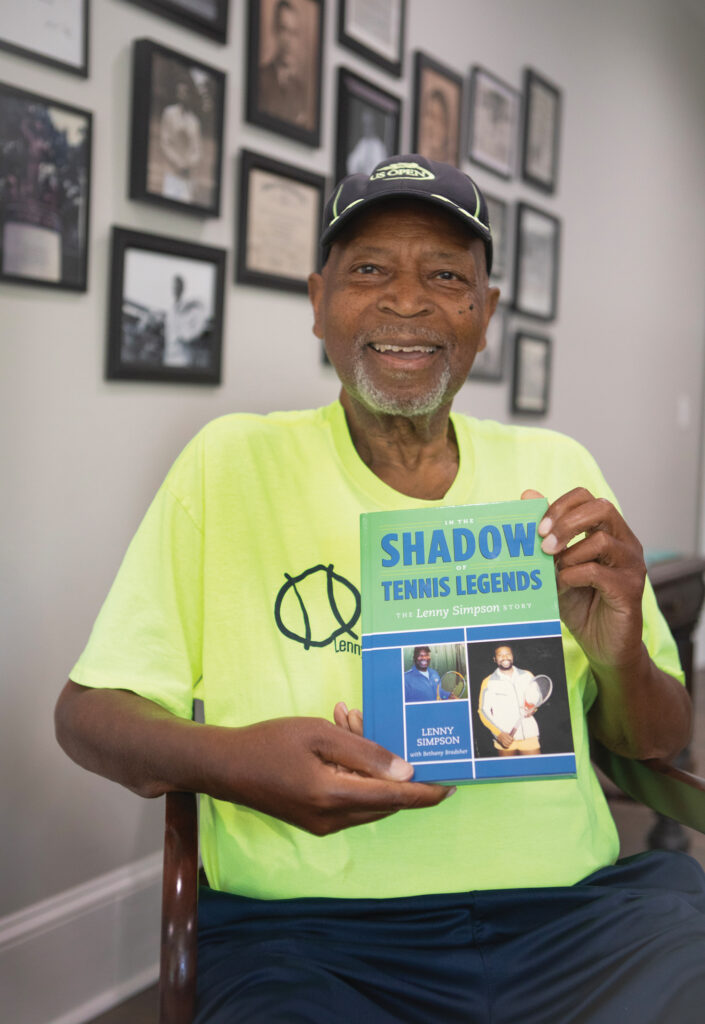

Simpson would go on to become a tennis great. He broke color barriers and won many matches as a top amateur and professional.

Dr. Eaton (1916-1991) also became famous, for his love of the community and his fight to end discrimination in New Hanover County Schools and sports and a 10-year battle to end discriminatory practices in healthcare in Wilmington.

He also led efforts to desegregate Wilmington College (now the University of North Carolina Wilmington), YMCA, Municipal Golf Course, and the NHC Library System.

With donations, the historically important house and tennis court have been preserved by Simpson and his wife, JoAnn, and is now serving a new generation of Wilmington tennis hopefuls. To date, One Love Tennis, Simpson’s nonprofit, has reached more than 20,000 youths with the message of inclusion through tennis.

This is that story from the beginning.

As an inquisitive 5-year-old in 1953, Lenny Simpson would watch his next-door neighbor Nathaniel Jackson, son of Dr. Jackson, walk down the sidewalk, turn right and disappear.

“Then I’d see him come back a little later drinking a Coca-Cola,” Simpson says. “One day I finally got up enough nerve to ask him, ‘Mr. Jackson where did you get that Coca-Cola?’ He said, ‘Well, I got it from the tennis court where I play. Would you like to learn to play tennis?’”

“What tennis court?” the child replied.

“The tennis court behind your house,” Jackson answered. “Do you want to learn?”

“Well yeah, but how’d you get that Coke?”

Everybody in the neighborhood went to Dr. Eaton’s.

“It was known as the black country club for us because we certainly couldn’t belong anywhere else. That was crucial. I probably would have never played tennis if that tennis court had not been there because that was the only opportunity I had to play,” Simpson said in a 2015 Wrightsville Beach Magazine interview.

Jackson took Simpson to see Eaton’s tennis court, then went to his mother to say her son wanted to learn how to play. Simpson’s mother didn’t want her young son bothering the adults.

“He’s just going to be in the way,” she said.

Jackson pressed this issue, but the answer was still no. Still, Simpson slipped over the field between the adjoining yards, hid himself under the bushes along the fence, and watched. He saw Jackson playing against Eaton with people watching along the sidelines. He also saw a young woman play.

“She was beating everybody — men, women, young and old,” Simpson says.

It was Althea Gibson, Dr. Eaton’s ward.

Jackson spotted the boy under the bushes and asked him, “Lendward, does your mother know you’re here?

“No.”

“Well, you may want to go home.”

“No, I want to stay and look.”

“OK.”

Simpson learned how the Cokes were distributed.

“If you lost a match 6-0, or love as it’s known in tennis, they call it putting a collar around your neck,” he says. “And you had to buy Coca-Colas for everybody at the court.”

The next time Jackson walked down the sidewalk drinking a Coke, Simpson told him he wanted to play tennis. Simpson asked Jackson to talk to his mother about the plan. The answer was still no.

But Simpson is said to have told her, “You can spank me. I’m going over there anyway.”

For two weeks he went to Eaton’s court. And for two weeks he got a spanking. Finally, his mother concluded if her son was willing to pay the price for disobeying her, she would let him play. The rest became history.

Jackson took Simpson to the court every day. Training started with running balls down for the adults, learning how to keep score, brushing the court, sweeping the lines, and always watching and learning.

“I had to have a work job,” Simpson says.

When everyone was finished for the day, he would go to the corner store at 15th and Orange to buy the all-important Coca-Colas.

Satisfied with the first steps of his training, Jackson, Eaton and Gibson began coaching Simpson. The three of them would stand next to him, instructing him to hit off the backboard.

“They taught me discipline, structure, hitting off that backboard watching the ball; back and forth, back and forth,” Simpson says.

As lessons progressed, Simpson realized he was watching one of the greatest females ever to play the game of tennis. Eaton had discovered 19-year-old Althea Gibson in Harlem, New York. She had a poor home life and wasn’t attending school. Eaton became her guardian and brought her to Wilmington, where she attended Williston High School.

“You know you’ve got Althea Gibson who is probably going to be the next world champion coaching you and teaching you the game of tennis,” Jackson told Simpson.

The boy embraced the chance to learn from this group and began to play matches against them.

When he was 8, the coaches entered Simpson in his first tournament sponsored by the American Tennis Association (ATA) at North Carolina College (now NC Central University) in Durham. The ATA was formed for black tennis players to compete around the country.

“At that time, we could not play in the USLTA, the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association,” Simpson explains.

His mother drove a group of boys to the tournament. He won the doubles championship with Leonard Hawes, who was 11. It was the first time Simpson’s mother saw him play tennis. She cried, realizing the talent her son possessed.

Eaton and Jackson introduced him to Dr. Robert Walter Johnson. For more than 20 years Johnson took young African-American tennis players into his Lynchburg, Virginia home. He fed and clothed them and trained them on a clay court in his backyard. On weekends during volatile decades of civil unrest, particularly in the South, he transported them to tournaments across state and racial lines.

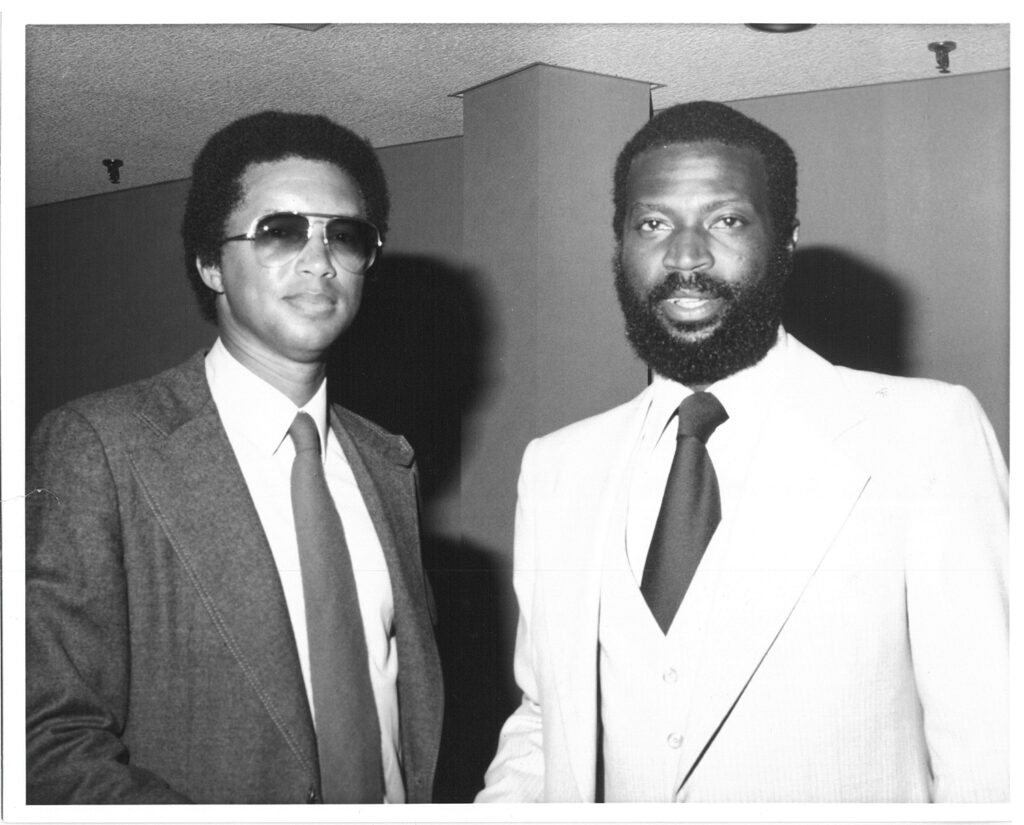

Both Simpson’s parents were educated. Eaton and Johnson encouraged them to allow him to live with Johnson during the spring and summer to play on the ATA junior development team. Simpson’s mother was hesitant, but his father wanted him to take advantage of the opportunity. At age 9 he moved in with Johnson and 10 other boys and girls. Johnson encouraged older children to mentor the younger ones. Fifteen-year-old Arthur Ashe was assigned to Simpson.

After Simpson played a tournament in Washington, D.C., a man approached Simpson about attending private school. Johnson and Eaton discussed the offer and agreed Simpson would benefit from a private education. At age 12 Simpson left Williston Junior High School to attend the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania.

As the country desegregated so did the USLTA.

Simpson’s career really took off in 1964. When he was 15, he played in the U.S. Open — the youngest male ever. He held that record until 1987, when Michael Chang became the youngest player by three months.

“I’m 15, playing at the U.S. Open in Forest Hills [New York] where blacks are not allowed to be members of that club. Arthur Ashe had played before me. Althea Gibson had broken the [color] barrier before that for Ashe. Ashe for me,” Simpson says. “I played Arthur Ashe in the second round. This was the first time two African-American males had ever played against each other in a major tennis championship.”

Ashe, older, more experienced and a seeded player, won the match.

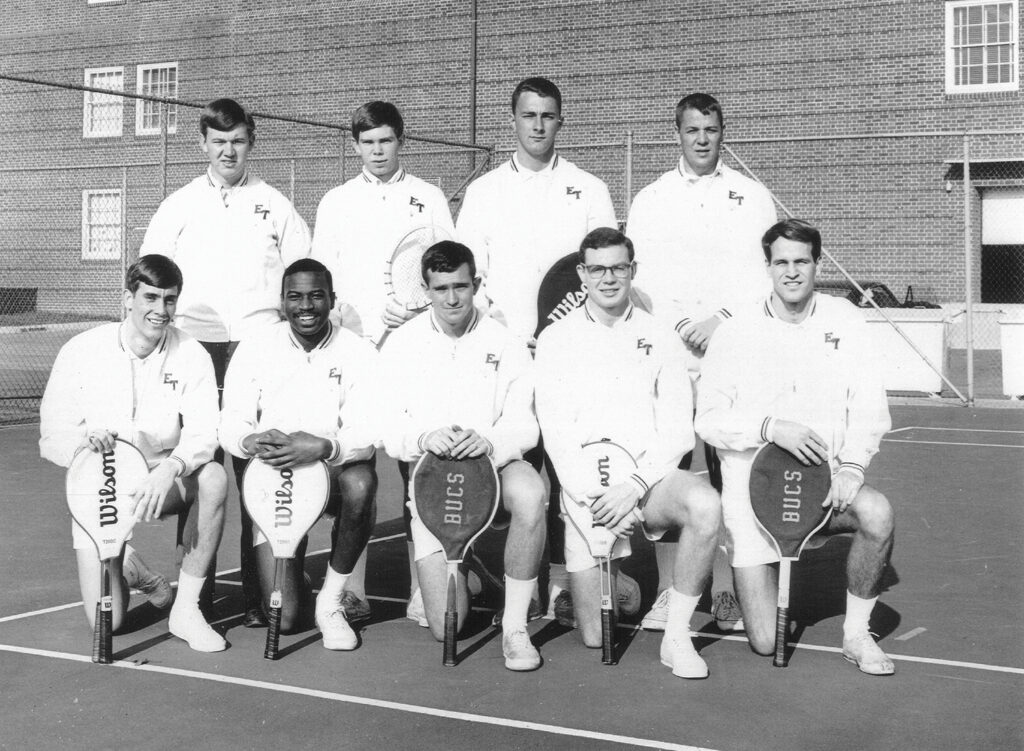

When he was in the 10th grade, Simpson transferred to Cheshire Academy in Connecticut. After graduation in 1968, Simpson wanted to attend Brown University. He received offers from several schools including Penn State, the University of Pennsylvania and UCLA, where Ashe went to school, but he was waitlisted by Brown. Instead, he chose East Tennessee State, a school that welcomed black players and offered a scholarship.

A week later Brown made an offer. But Simpson, a man of his word, went to Johnson City to attend ETSU, where he majored in physical education and minored in psychology. He was ranked No. 1 in the Ohio Valley Conference for three straight years and played basketball for the school. It is also where he met his future wife, JoAnn.

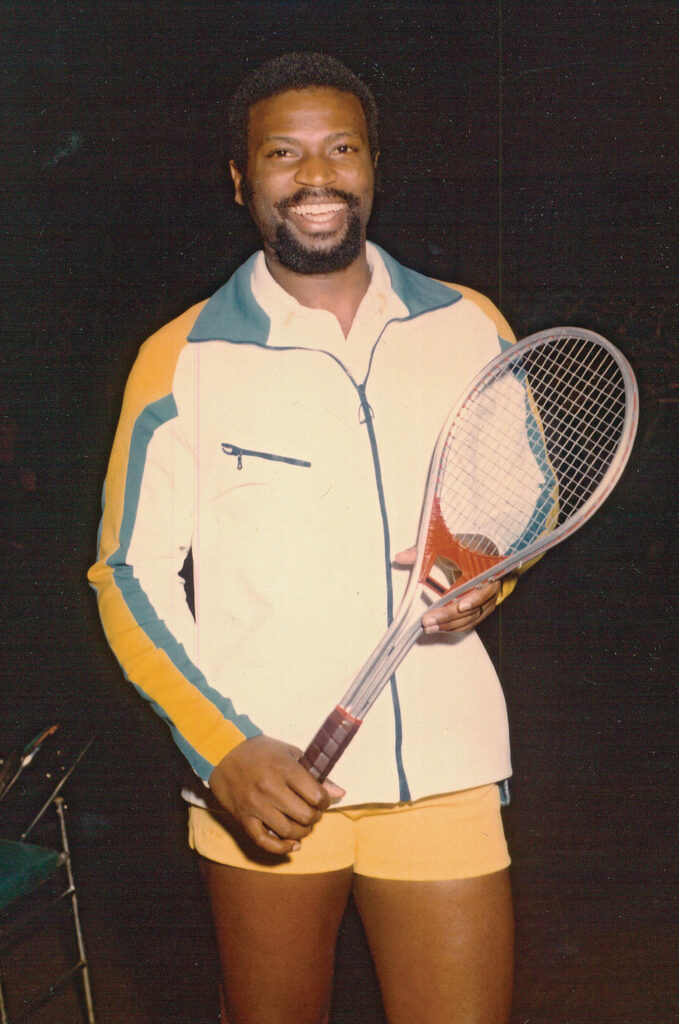

The summer before graduation Simpson took a tennis director position in West Bloomfield, Michigan. In 1973 he graduated from ETSU and turned professional. He and JoAnn married on June 1, 1973.

In 1974 Simpson was the first African American to play World Team Tennis for the Detroit Loves and he qualified for Wimbledon. He remained on the professional circuit until 1980, when he left to start a tennis business and a family.

Simpson and JoAnn moved to Tennessee, where he ran tennis programs and clubs and raised two daughters, Celeste and Jennifer. The couple owned an indoor/outdoor racquet club from 2005-2010.

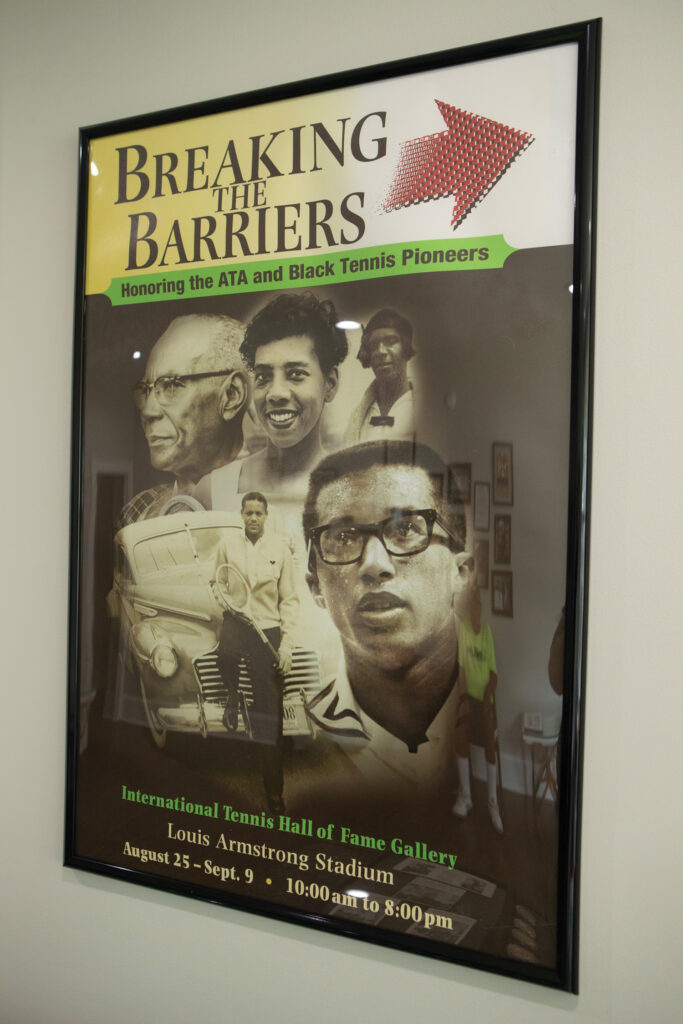

Simpson was inducted into the Cheshire Academy Hall of Fame in 1989, the North Carolina Tennis Hall of Fame in 2011, the Greater Wilmington Sports Hall of Fame in 2012, the Black Tennis Hall of Fame in August 2014, and the Hill School Basketball Hall of Fame in November 2014. He is also featured in Breaking the Barriers: The ATA and Black Tennis Pioneers exhibit at the International Tennis Hall of Fame, in Newport, Rhode Island.

In 2013 Simpson returned to Wilmington with a desire to make a difference in the community as Dr. Eaton had done years before. He started the Lenny Simpson Tennis and Education Fund and One Love Tennis, a nonprofit organization that provides free instruction and academic support for youth.

“That’s what Dr. Hubert Eaton did for me. So, I’m trying to give that back,” Simpson says. “By the grace of God opening up all the doors and a lot of help from a lot of people — young guys I grew up with in this town have been willing to help me when we were not even supposed to be friends growing up because of the color of our skin.”

“We want to give them hope just like someone told me at 5, 6 and 7 that you can succeed and do something with your life,” he says. “We have kids from Landfall and kids from the projects on the same court. All they know is they are both trying to hit a tennis ball and they’re getting to know each other and become friends. They’re learning they’re not different than each other.”

The House, The Court, The Pool

In 2016 One Love Tennis purchased the craftsman style house and property from the family of Dr. Eaton. The 1929 house has a historical marker. The Eatons made additions on both sides with wings in the 1950s and added the upstairs.

With a private donation, One Love Tennis began restoring. The exterior was the first priority, the tennis court was second. Then came a $50,000 donation from native son and basketball icon Michael Jordan.

“We were very lucky to come back 65 years later and restore the place,” Simpson says. “The restored historic court is for neighborhood kids.”

The One Love program already had ages 5 to 11 enrolled.

“The house was purchased to be a safe haven for those ages 12 to 18,” he says.

Simpson believes all things are possible with God.

“Jesus Christ told me that all things are possible. That’s the premise I work on,” Simpson explains. “The more you tell me no, that’s telling me yes. If you tell me no, that means I’m on the right track, it’s gonna be done.”

The interior was next, and now hosts an academic enrichment program for 12-to-14-year olds where the great Althea Gibson once lived on the second floor. A balcony overlooks the restored clay court. The heavily fortified exterior door is a reminder that Wilmington’s past was not always kind.

Monday through Thursday there are regular programs in the education center. The court is used every day.

“We teach every section of this town,” Simpson says. “Rich, poor, black, white, everybody is on this court. That’s the way Dr. Eaton did when he had this court.”

One Love Tennis, The Lenny Simpson Tennis and Education Fund

Since April 2013, Simpson’s nonprofit has provided year-round instruction and life skills/mentoring free of charge at seven locations to students including at-risk youth.

The One Love program has screened the acclaimed documentary Althea to every middle and high school in New Hanover County, reaching close to 20,000 students with the story of Wilmington’s trailblazing world champion.

Simpson isn’t as active after suffering a stroke in 2021, but One Love Tennis continues with expanded programs serving kids just as Dr. Eaton did so many years ago. And Simpson is back on the courts with the kids.

“Every day,” he says.

Growing veggies in tower gardens have the kids and Simpson excited. They are growing vegetables to eat and sell to area restaurants.

“They learn how to talk to people and sell their produce,” Simpson says.

“I had no idea I’d come back here and buy this property. Dave and Carolyn McLemore started the whole process. Without them, maybe this would never have happened.”

The house has been featured on national television throughout its renovation, including CBS, ESPN, and the Tennis Channel.

Lenny and JoAnn now live 60 feet from where he grew up. The Simpson home is still standing as well. It was sold three years ago after Simpson’s mother, Helen Wills Moody, passed away.

“I came through those same gates when I was 5 years old. Same place, same bushes, everything, it has not changed,” Simpson says with wonder. “Look at me now, with my wife and family giving out groceries every month. The community has been unbelievable. When they can see what you are doing, they’ll write a check.”

Pat, a terrific article on Dr. Eaton’s Orange Street home. He was a good friend of mine for a quarter century, and the finest man in Wilmington. We have been fortunate to have him. A man of many talents. (I am author of Wilmington A Pictorial History)