Sustainable Construction For the Future

Lessons learned from a Florida residential community that bested Hurricane Ian

BY Fritts Causby

New techniques are making it possible to minimize the impacts of a hurricane, and the example of Babcock Ranch could have useful applications for communities across the coastal regions of North Carolina.

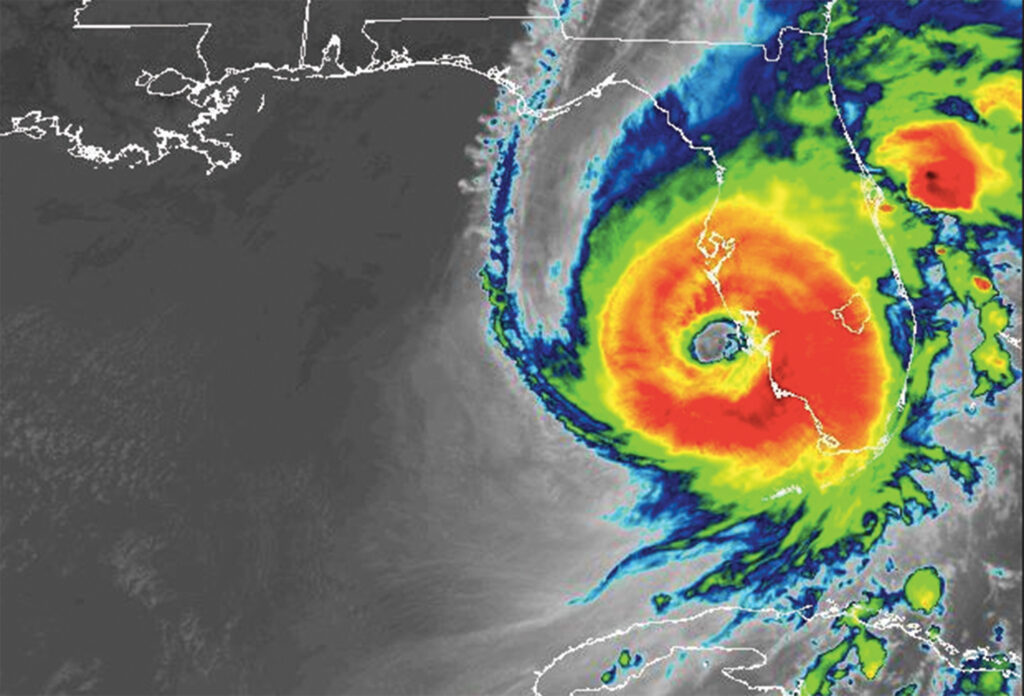

Babcock Ranch is a residential community in Fort Myers, Florida. It made national headlines for weathering Hurricane Ian, which made landfall on Cayo Costa Island as a Category 4 hurricane in late September 2022.

Like Hurricane Florence, which made landfall near Wrightsville Beach in 2018, many of the impacts from Ian were from water inundation instead of wind, as initially predicted.

The slow-moving nature of Hurricane Florence resulted in record-breaking rainfall, around 34 inches. Combined with a powerful storm surge, the result was widespread flooding across the Carolinas. New Bern, around 37 miles from the nearest beach but located adjacent to the Neuse River, had approximately six feet of storm surge. The storm surge reached nearly 10 feet in nearby Oriental, North Carolina.

The storm surge from Hurricane Ian ranged between 10 and 15 feet. In a six-hour period on Sept. 28, Ian produced around 8 to 12 inches of rain. There were widespread power failures. Sanibel and Pine islands were ravaged as was much of Florida’s southern coast, with one notable exception — Babcock Ranch.

Other than downed street signs and fallen palm trees, Babcock Ranch for all intents and purposes withstood Hurricane Ian with barely a scratch.

Its developers attribute the lack of damage to sustainable construction practices incorporated into the design, including strategically placing large retention ponds around the community perimeter, burying all power lines underground, and engineering streets to absorb floodwaters.

The community is powered by an 870-acre solar farm with 650,000 panels. Excess power produced during the day is sold back to the grid. Generators powered by natural gas, considered by many to be an inexpensive and clean energy source, provide necessary power at other times. While many neighboring communities lost power during Hurricane Ian, Babcock Ranch did not — not even internet service — aided by the fact that all the cabling is below ground.

Another factor that helped Babcock Ranch weather the storm is that it is 30 miles from the coast.

The community feels its water mitigation, solar energy source and having power lines buried helped minimize storm impacts. These techniques could be implemented anywhere.

“From a very limited view, the ideas at Babcock Ranch make sense depending on the feasibility of the economics of the deal. The concept definitely seems marketable, if for no other reason than it could give the homeowner one less worry during hurricane season,” says Wrightsville Beach Mayor Pro Tem Hank Miller III, senior vice president of Cape Fear Commercial.

“Some of the principles employed at Babcock Ranch would work here,” says Wilmington architect Anna Dietsche of Dietsche + Dietsche Architects. “Most of my knowledge for extreme hurricane weather has been put to use on Bald Head Island, where the golf course’s lagoon system is designed to capture and drain floodwaters similarly to Babcock Ranch. All the electrical lines are underground there too, and the power is shut off before a hurricane hits. The difference is that Bald Head is an island, so when a hurricane hits, the wind is not slowed as it would be at Babcock Ranch, where it slows with the friction of 30 miles of land travel before it arrives.”

Since Hurricane Florence, local coastal building codes have been strengthened to help ensure local structures can withstand wind speeds up to 157 miles per hour. The former level was 130 miles per hour.

“Hurricane Florence changed the way we look at hurricanes on Figure Eight Island and Wrightsville Beach,” says Intracoastal Realty broker Buzzy Northen. “You are seeing a lot more waterfront homes using concrete pilings as they are much heavier and have more weight-bearing capacity.”

Whit Honeycutt with North State Custom Builders said all contractors are upgrading windows, roofs, wraps and siding to deal with wind-driven rain, which caused a significant amount of damage to homes from Florence.

“Quality roofing contractors are also utilizing roof underlayments that are vastly superior to those used just a few years back,” he says.

The idea of subterranean power lines is also gaining ground.

“Back in 1999, I was campaign manager for Ed Paul when he ran for mayor. We approached Duke, which was CP&L at the time, and asked about the possibility of burying power lines as an idea for a campaign goal,” says Miller. “They essentially told us that it would be prohibitively expensive and therefore impossible; they preferred having them overhead for easier repairs.”

Duke Energy now has a targeted undergrounding program, that uses smart data to identify the most outage-prone power lines. Moving those lines underground can significantly reduce outages and momentary service interruptions, and it can lessen costs and quicken restoration time after a major event for all customers.

“The town of Wrightsville Beach is currently talking about the idea, and has been talking or meeting with Duke again recently,” Miller says. “Sometimes ideas do happen, just on a different timeline than we envision. Using renewables is kind of a no-brainer to me if the investment dollars make sense and the actual impact on the public is minimal. No matter where you are politically, we should all be able to find common ground when it comes to the bottom line and the convenience factor of things.”