Street Railways in Wilmington

Inter-urban connectivity

BY Pat Bradford

As Wilmington continues to consider revamping its public transportation system, while also considering bringing back passenger rail, it may be helpful to have a broader picture of the city’s rich history of public transportation.

The city of Wilmington was founded in 1739. Its population at the 1840 census was 5,335, the largest in the state. By 1860, the population was 9,552, and by 1900 had more than doubled to 20,976.

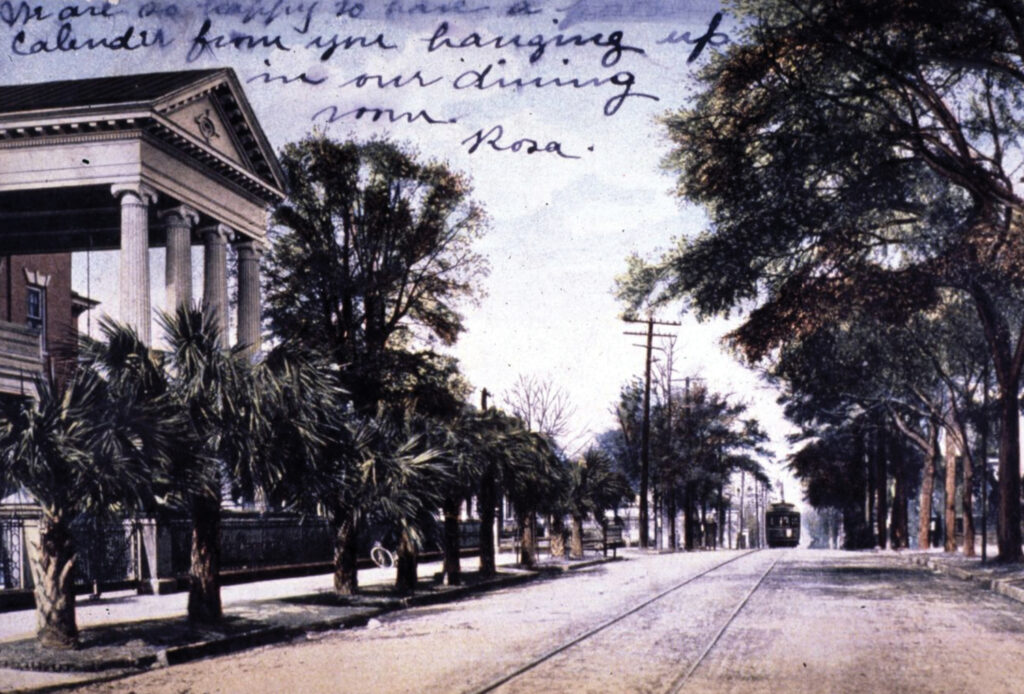

Public transportation in the city began in 1888 with horse-drawn railcars.

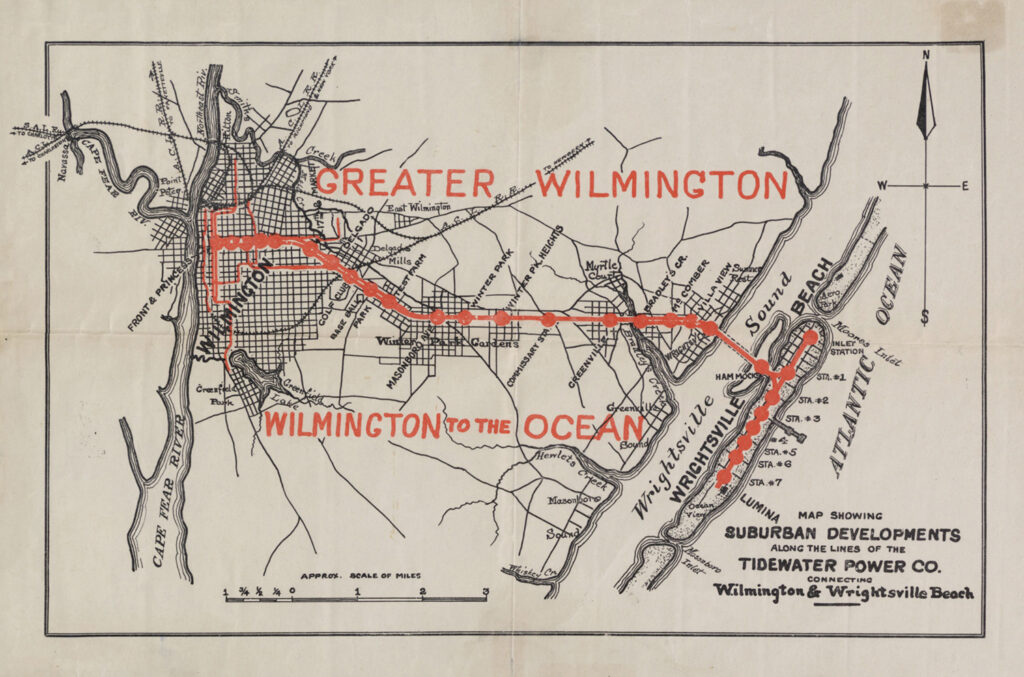

Street railways would operate over a period of 51 years. They were Wilmington Street Railway Company, later reorganized as the Wilmington Electric Street Railway Company; Wilmington Sea-Coast Railroad; Consolidated Railway, Light and Power Company; Ocean View Railroad (Sea View Railroad) and Tidewater Power Company.

Organization to provide service began in 1887 with a 50-year state-approved charter to the Wilmington Street Railway Company. The company president was J.D. Bellamy Jr., the vice president was Charles M. Steadman, the secretary/treasurer was Frank H. Steadman, and W.H. Howell was the superintendent. The road opened on July 17, 1888, with 4.65 miles of horse-drawn railcar line.

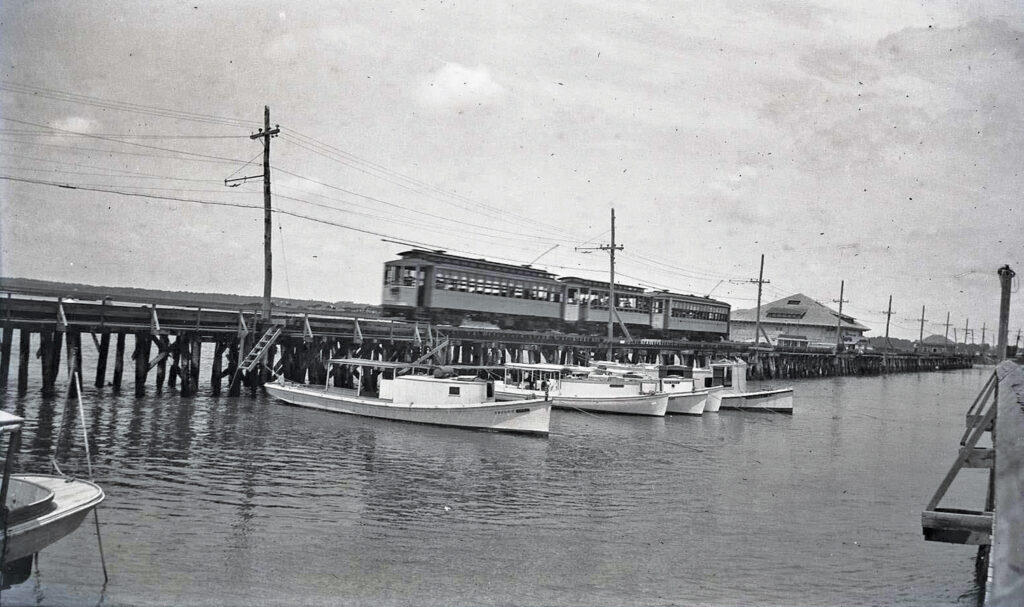

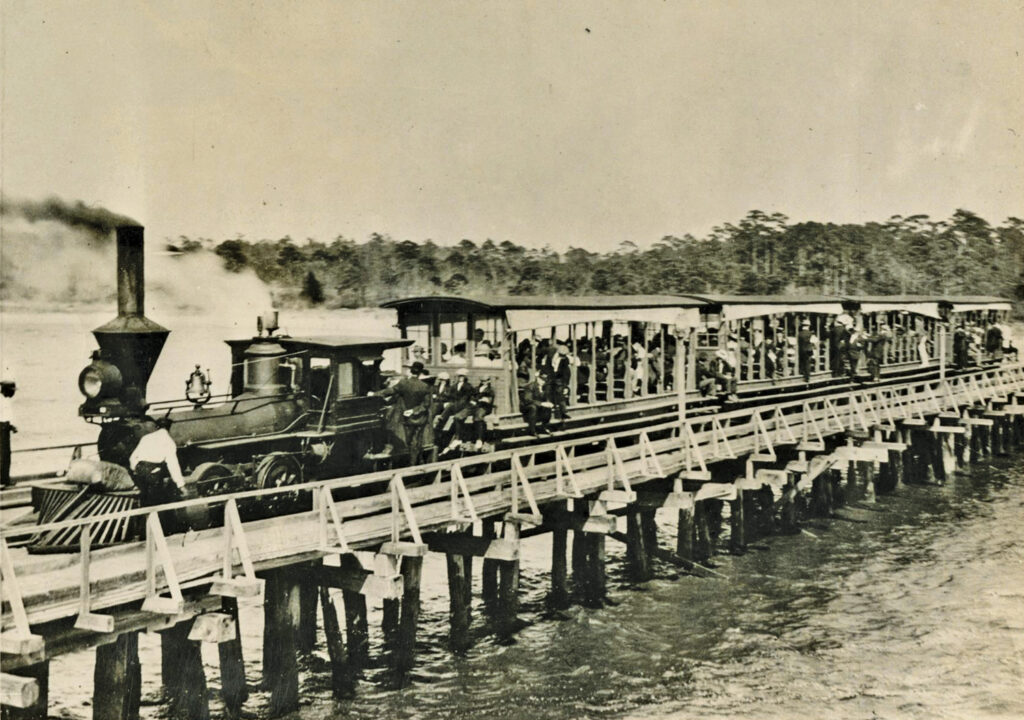

Wilmington Sea-Coast Railroad also launched that year, offering steam-powered rail service for passengers and freight between Wilmington and Wrightsville Beach.

Wilmington Sea-Coast Railroad acquired Ocean View Railroad, aka Sea View Railroad, in 1891. Its officers were E.S. Latimer, president; B.G. Worth, first vice president; J.R. Noland, secretary and general manager; and G.H. White, general passenger and freight manager.

With the acquisition, the company owned the 11.81-mile rail line from Wilmington to Atlantic Station. The route from Wilmington to Hammocks — present-day Harbor Island — was 10.31 miles, and from Hammocks to Atlantic Station was 1.51 miles.

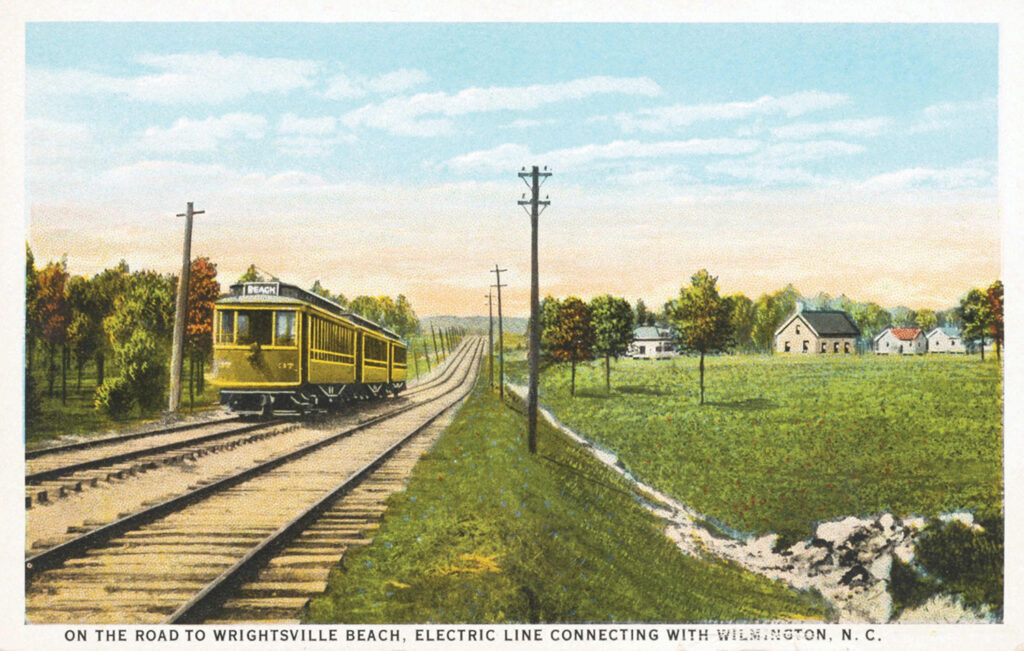

Wilmington Sea-Coast Railroad’s steam-powered rail was replaced by an electric trolley in 1902. For the year ending Dec. 31, 1904, the sixth annual report of the North Carolina Corporation Commission reported the routes of the Wilmington Sea-Coast Railroad as “Wilmington, Delgado Mill, Greenville, Bradley’s Creek, Wrightsville and Ocean View.”

Meanwhile, in 1892 with what was called an influx of funds from “northern financiers,” the Wilmington Street Railway Company converted from horses to electricity with an electric streetcar system.

Receiving authorization by the state legislature to supply electric power to the city, the company was reorganized as the Wilmington Electric Street Railway Company. Officers were E.L. Hawks of New York, president; J.H. Barnard, vice president and general manager; F. O’Conner, secretary: and J.G. White, treasurer.

Capital stock of $300,000 was authorized. Contracts for improvements went to Lewis & Fowler Manufacturing Company of Brooklyn, New York, for cars and rails, to J. G. White & Company, New York, for the construction and laying of tracks, and to Ball Engine Company of Erie, Pennsylvania, for a steam plant.

The July 1892 Street Railway Journal, published by the McGraw Publishing Co., reported on the reorganization: “For four years the Wilmington Street Railway Co. have had in operation in that city seven small horse cars over about four miles of track; and in December last this line was purchased by a syndicate, several of whom had been instrumental in the organization of the Asheville and other North Carolina roads.”

This construction detail was included in the Journal’s 1892 report: “The track of the old horse car line had been laid with a thirty-two-pound T rail laid upon cross ties, four feet apart.”

The company had 7 miles of track, including 1.5 miles of steam track connecting all railways that entered Wilmington.

Electric car equipment consisted of six eight-seat open cars and two 16-foot 16-seat closed cars. Four of the 11 horse-drawn cars had been purchased and overhauled and repainted for use as trailers. Purchase of a Baldwin compound steam motor of the latest pattern was for transferring cars and freight. By 1894 the company’s equipment had doubled.

The American Street Railway Investments Magazine reported that at the end of 1901, the Wilmington [Electric] Street Railway Company’s new officers were Hugh MacRae, president; C. P. Bowles, secretary & treasurer; and A.B. Skelding, general manager.

By 1902 this rail line owned 11 motor cars and two trail train cars that ran over 4.5 miles of electric track, with 1.5 miles still powered by steam.

MacRae formed the Consolidated Railways, Light and Power Company that year. He consolidated the two rail systems in New Hanover County and purchased Wilmington’s street railways as well as the light and power facilities. He had also established a company near Rockingham, North Carolina, on the Pee Dee River to generate electricity.

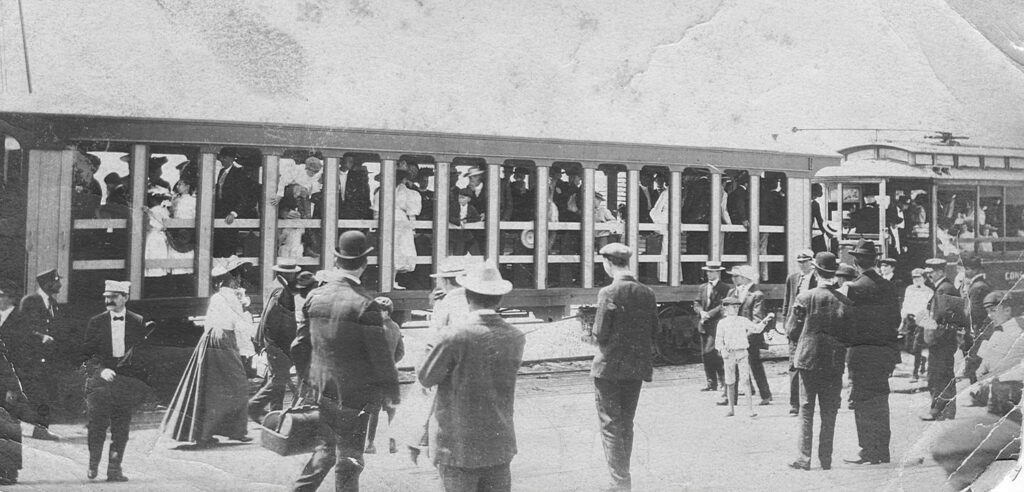

Now beach-bound passengers could board downtown rather than starting their trip a mile away at the streetcar yard at Ninth and Orange streets.

A June 14, 1902, Wilmington Morning Star article reported “… Consolidated Railways, Light and Power Co.’s new electric headlights have also arrived and will be put on the cars all of which have been nicely repainted. The new equipment will add much to convenience and comfort of travel.”

The number of passengers transported during the fiscal year ending June 30, 1902 was 1,034,904.

The Dec. 31, 1902, fourth annual report of the North Carolina Corporation Commission listed Consolidated Railways, Light & Power Company as operating six box passenger cars equipped for electric power and 13 open passenger cars equipped for electric power on 4.95 miles of track within the city limits of Wilmington. There were 10.9 additional miles of track outside the city limits.

Five years later, the report noted the company operated seven box passenger cars equipped for electric power, 14 open passenger cars equipped for electric power, two other passenger cars equipped for electric power, and three snowplows on 6.71 miles of track within the city limits of Wilmington. There were 12.27 miles of track outside the city limits.

During the company’s fiscal year ending June 30, 1907, the number of passengers had increased to 2,222,531. Company officers had not changed since 1902.

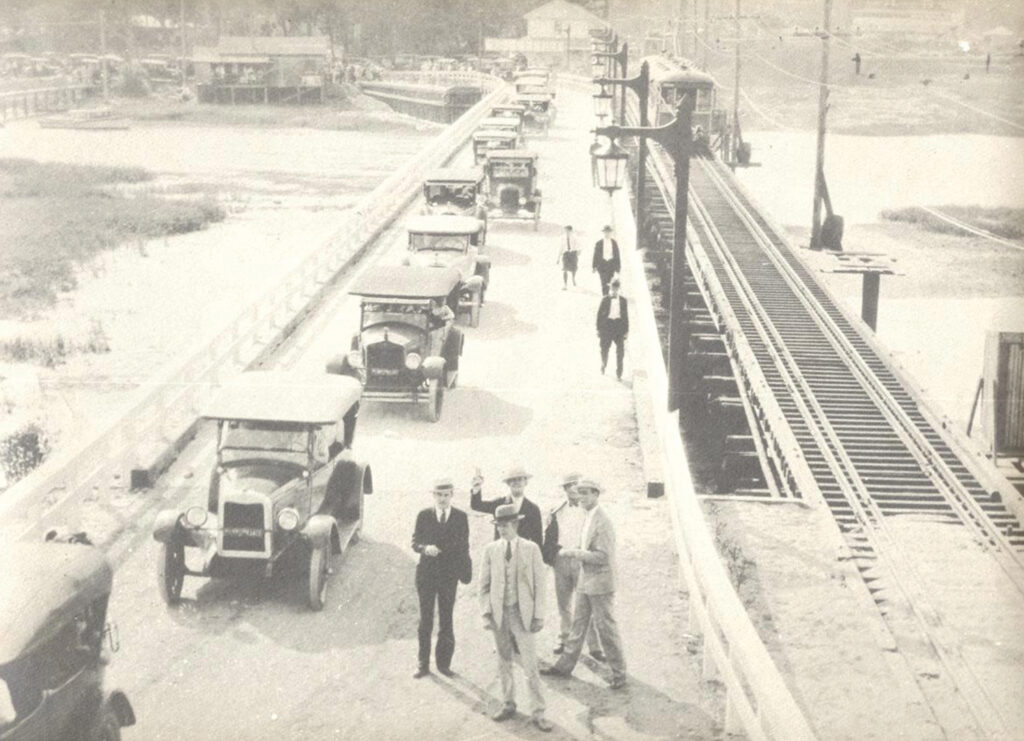

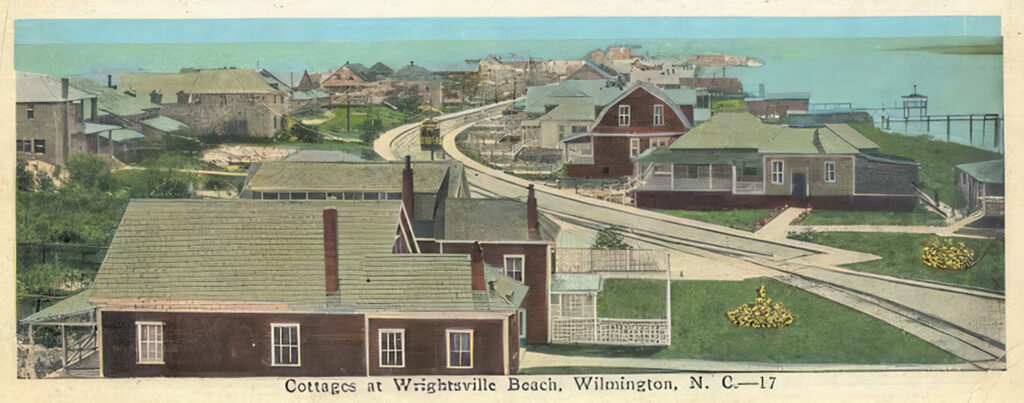

There was no automobile access across Banks Channel onto the barrier island of Wrightsville Beach until 1935.

MacRae, who also built Oceanic Hotel and the Harbor Island Pavilion, built Lumina Pavilion to promote the use of electricity in 1905, as historian Susan Taylor Block described in Lumina Part 1 in the July 2008 Wrightsville Beach Magazine. The last stop on the beach car line to Wrightsville Beach was Lumina. To the north the last stop was Inlet Station.

MacRae formed the Tidewater Power Company in October 1907 while retaining ownership of the Wilmington streetcar system under this new name.

Tidewater employed 50 people serving 2,387,209 passengers by the fiscal year ending July 30, 1908. Company officers were Hugh MacRae, president; H. Woollcott, secretary; R J. Jones, treasurer; and A. B. Skelding, general manager.

By Dec. 31, 1908, Tidewater had in service 19 box passenger cars equipped for electric power, six open passenger “trolley” beach cars equipped for electric power, and three trailers on 7.42 miles of track within the city of Wilmington. There were 10.94 miles of track outside the city limits.

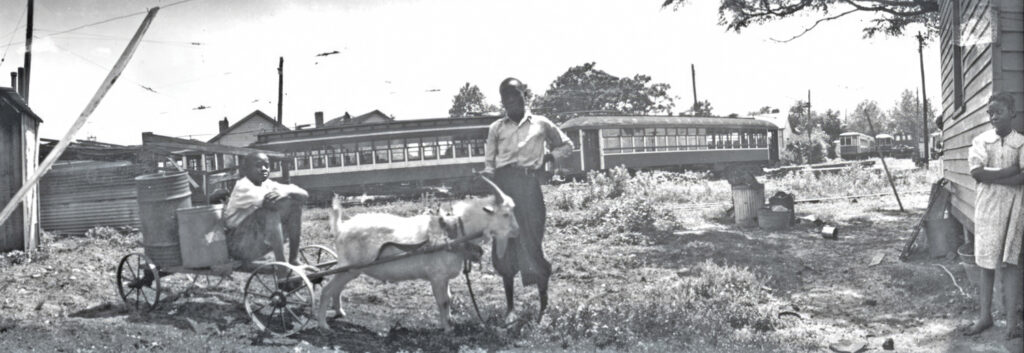

In 1910 the North Carolina population was 2.2 million. Only two cities had grown to more than 25,000 people; Charlotte with 34,014 had superseded Wilmington (25,748), as the most populous.

When the Carolina Shipyard opened to build ships for World War I, the Wilmington streetcar lines were extended out a mile to the new shipyard.

The A. E. Fitkin & Company of New York City acquired control of the Tidewater Power Company in April 1922. The Electric Railway Journal of that month reported the properties included in the sale: “An electric light and power plant, a gas plant and electric railway system serving the North Carolina city and inter-urban territory. The inter-urban line runs 12 miles to Wrightsville Beach on the ocean where the company has an amusement pier, a casino and a large auditorium for convention purposes.”

The 22nd report of the North Carolina Corporation Commission for the Biennial Period, 1923-1924, reported, “Electricity is furnished for lighting purposes to the following cities and towns: Wilmington, Rocky Point, Magnolia, Kenansville, Warsaw, Faison, Calypso and Wrightsville Beach. Electricity is furnished at wholesale to the following towns: Burgaw, Wallace, Rosehill and Mount Olive.”

Tidewater Power Company created new traffic arrangements in 1924 and a new type of transportation service was operated by the Coast City Transportation Company in its inaugural run in Wilmington. It required two gas engine passenger motor buses to maintain a 20-minute schedule. A third bus was kept in reserve and would operate during periods of heavy traffic.

“One of the noteworthy facts concerning the line is that it will go out of its regular path morning and evening for two or three trips in order to take care of the high school children,” reported the Electric Railway Journal of Oct. 25, 1924.

Free transfers were issued from the new buses of the Coast City Transportation Company to the streetcars, and exchange tickets were issued from the streetcars to the buses on payment of an extra 3 cents. The buses had a seating capacity of 16 passengers.

The 23rd report of the North Carolina Corporation Commission for the Biennial Period of 1925–1926 showed the Wilmington streetcar system had increased to 33 miles of track, of which 9 miles were double tracks. The fares were 7 cents.

Even though inroads were being made by automobiles, Tidewater continued to invest in improvements.

“Tidewater Power Company is reconstructing its lines between Wilmington and Wrightsville Beach at a cost of approximately $50,000. The project included relaying of 32,000 feet of new and heavier rail. Wrightsville Beach is North Carolina’s leading ocean resort and the new line will double the service capacity,” the Electric Railway Journal noted in its Feb. 19, 1927 edition.

The age of the motor car began when German inventor and engineer Karl Benz applied for a patent for his three-wheeled vehicle powered by gas on Jan. 29, 1886. The first successful American gas engine was designed in 1893. In Detroit, Henry Ford built his first car in 1896. The prosperity of the 1920s allowed many Americans to afford refrigerators, stoves, washing machines and automobiles.

The Henry Ford analysis of Railroads vs. Automobiles notes that by 1920 there were more than 468,000 motor vehicles registered in the United States. By 1921, 136,000 North Carolinians owned automobiles.

The rise of the automobile came with a decline in rail passengers, not just in cities but in rail travel nationwide.

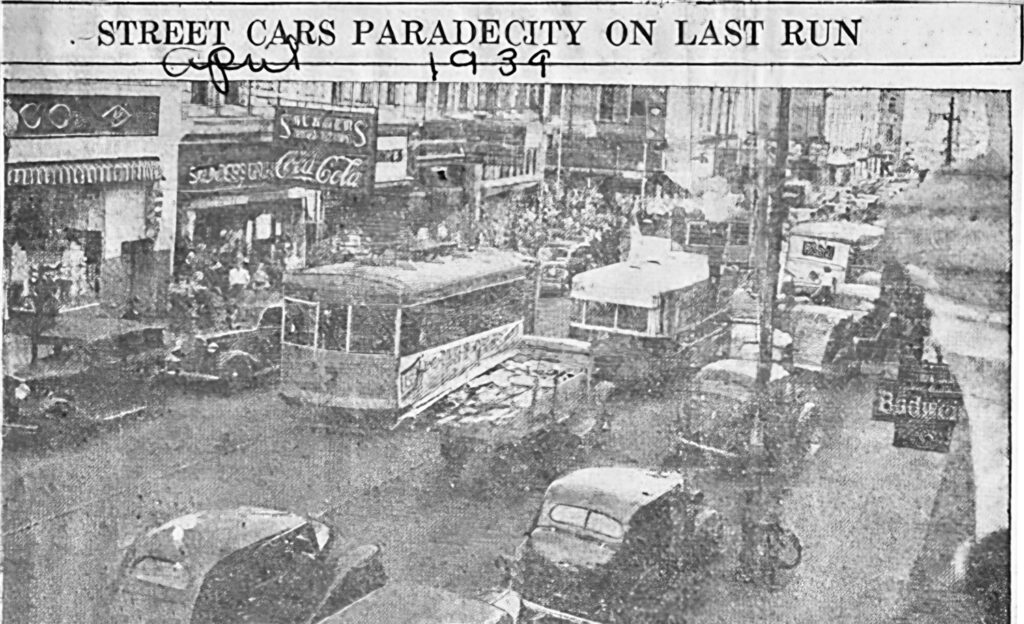

Wilmington’s electric streetcar companies ended operations April 18, 1939.

Shoo Fly

In the late 1800s the resort of Carolina Beach had a pavilion, hotel and boardwalks for beachfront recreational activities, including dancing, but the Federal Point peninsula was only accessible by boat. A steamboat carried passengers 17 miles down the Cape Fear River from Wilmington to a dock near Sugar Loaf. A small steam engine train carried passengers from the river across to the Carolina Beach oceanfront pavilion. The train was called the Shoo Fly, in what is understood to be a reference to the prolific biting flies and mosquitoes that plagued the marshy area.

The pavilion, built in 1887 by Capt. John W. Harper, a steamboat captain and owner of the Wilmington & Southport Steamboat Company. Harper was instrumental in the development of Carolina Beach. Harper was born on Masonboro Sound in New Hanover County in 1856 and died in 1917. He is buried in Oakdale Cemetery.

The Carolina Beach pavilion burned down on Dec. 8, 1910.

A state charter was granted in 1919 to the Carolina Beach Electric Railroad for a line between Wilmington and Carolina Beach but there is no evidence that it was ever built.

Lumina Pavilion

Lumina Pavilion opened on June 3, 1905. The pavilion was built by the Consolidated Railways, Light & Power Company to draw visitors to the beach and to encourage them to ride the trolley. The original structure was 300 feet long and two stories in height, stretching from the high-water mark on the beach to within 20 feet of the trolley tracks. It was later expanded to include a larger ballroom, an orchestra shell, and dressing rooms. Lumina was a place for music and dancing and featured some of the most famous big bands of the times. Appropriate evening attire was required or you would be quickly escorted outside. It even offered silent movies on a screen built in the surf. The Wrightsville Beach landmark survived the Great Fire of 1934 and Hurricane Hazel in 1954 but was finally done in by the changing times and attitudes. It was demolished in 1973.

—The 110 People Places and Events That Shaped WB,

Wrightsville Beach Magazine, January 2009

North Carolina Railroads

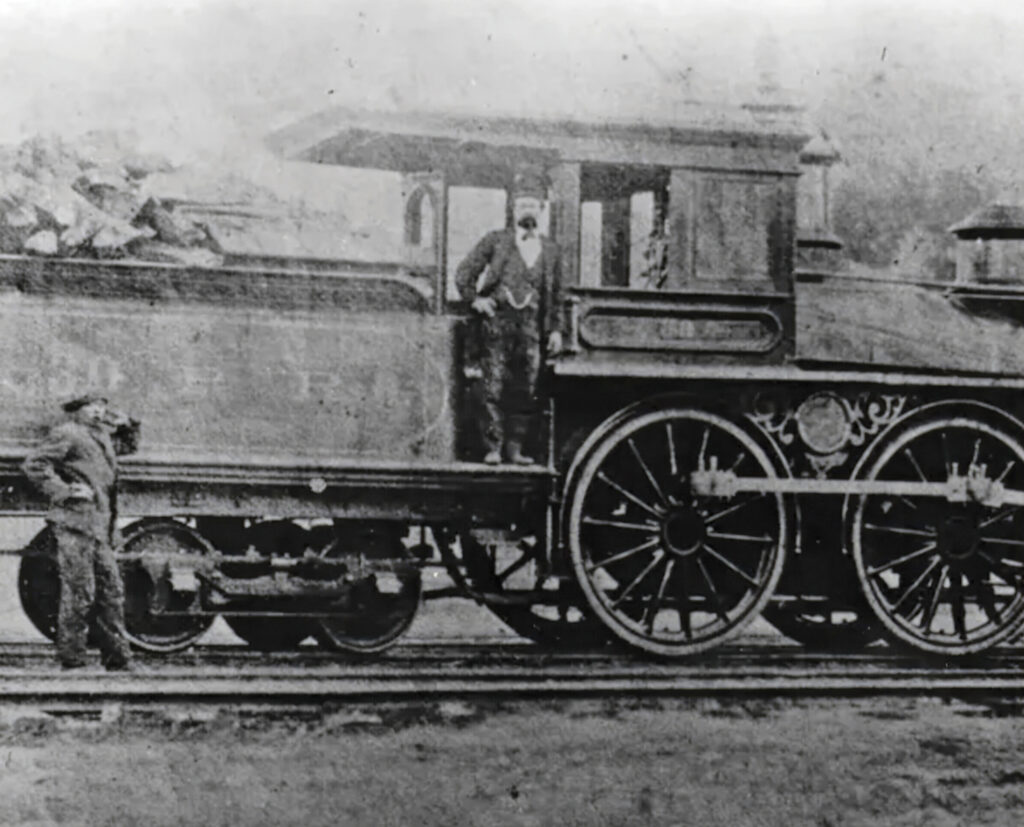

The first railroad in North Carolina, the Wilmington & Raleigh Railroad, began construction in 1836 and completed its first route in 1840. It was the longest railroad in the world, with service from Wilmington to Weldon in Halifax County and Rocky Mount totaling 161.5 miles. It was renamed the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad in 1854 and sold to the Atlantic Coast Line in the late 19th century.

The first North Carolina state street rail charter passed the General Assembly in February 1867 granting the city of Fayetteville a charter for the Fayetteville Street Railway Company to operate a “two-mile street railroad propelled by animal or other power.”

In 1881 legislative acts were passed granting charters to the Asheville Street Railway Company and the Raleigh Street Railway Company, both using horses to pull their cars.

Rail In Today’s News

New Wilmington to Raleigh Passenger Rail Route

In September 2023 Wilmington Mayor Bill Saffo met with the U.S. Department of Transportation’s federal railroad administrator to promote the possibility of new passenger rail projects in North Carolina, including the city’s bid for Wilmington-to-Raleigh passenger service.

In December 2023, a $500,000 DOT grant was awarded to identify and develop a proposed rail corridor to connect Wilmington to Raleigh. The proposed rail corridor would provide new service on an existing rail alignment, part of which has been abandoned and would need to be reconstructed, to include new stations. This corridor was one of seven in the state selected to receive a total of $3.5 million in grant funding.

Freight Rail Improvements

In December 2023, a North Carolina Department of Transportation announcement stated a partnership with the North Carolina State Ports Authority would each provide approximately $2.8 million in funding for construction of new tracks at the port. The state and Wilmington Terminal Railroad also announced track improvements at the port at just over $590,000 each.

—-

Sources:

www.carolana.com, J.D. Lewis

NC DOT Railroads, Street Railways

“Street Railways” by Walter R. Turner

The Street Railway Review 1892

The Street Railway Journal 1892

Johnsons Electrical & Street Railway Directory 1894

The American Street Railway Investments magazine 1902

Wilmington Morning Star newspaper 1902

North Carolina Railroad Commission reports 1898-1902

North Carolina Corporation Commission reports 1902-1924

The Electric Railway Journal 1917-1939

Railroads vs Automobiles, Henry Ford