Plantation Row

BY Jack Fryar

The image of Tara the fictional plantation featured in Margaret Mitchell s Gone with the Wind inevitably surfaces when the word plantation comes to mind. The term plantation refers to the size of the land holdings not the house in which the owner lived. During the colonial period from the early 17th century until American independence the homes tended to be fairly modest compared to many great homes of the Antebellum era.

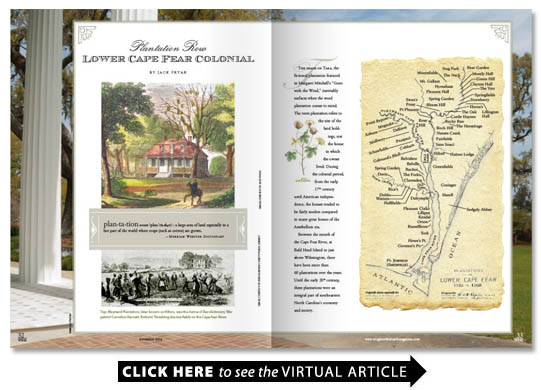

Between the mouth of the Cape Fear River at Bald Head Island to just above Wilmington there have been more than 60 plantations over the years. Until the early 20th century these plantations were an integral part of southeastern North Carolina s economy and society.

The first plantations on the Cape Fear were those of Barbadian settlers led by John Vassall who attempted to colonize the region between 1664-1667. The colonists spread up and down the river and its tributaries from a central trading post and compound at the mouth of Town Creek. Charles Towne so named by the Barbadians to honor England s King Charles II failed after three years. Its settlers numbering as many as 800 at the colony s peak left Cape Fear for places like Barbados Massachusetts Virginia and the settlement established by Sir John Yeamans at Port Royal to the south.

While King Roger Moore s Orton Plantation is perhaps the best-known plantation in the lower Cape Fear there were many others. Looking at maps of the region the names of great estates from days past litter the riverbanks and creeks that feed into the Cape Fear. Bald Head Belvidere Clarendon The Forks Greenfield Hilton Kendal and Lilliput are just a small sampling of the great land holdings that made the plantations of the lower Cape Fear the epicenter for commercial social and political activity in North Carolina. The influence of Cape Fear plantations and the men who owned them played an integral role in the development of the colony and state one that would last until well into the 20th century.

Plantations on the lower Cape Fear the only river in North Carolina that has direct access to the Atlantic Ocean initially traded in timber and shingles as well as the tar pitch and turpentine harvested from the abundant longleaf pines of the region. Collectively known as naval stores the longleaf s products were vital to shipbuilding efforts in England its American colonies and the great navy and merchant fleet that was the source of England s power. For decades North Carolina in general and the Cape Fear in particular were the largest exporters of the naval stores used for maintaining England s oak ships. The seasoned timbers harvested in North Carolina were used to expand the British fleet making England s the most formidable navy on the seas. Naval stores would be a leading export from Cape Fear plantations until the advent of steam engines began.

As profitable as naval stores were rice became the real king of the exports along the Cape Fear. In the Carolina lowcountry the grain arrived aboard a merchant ship captained by James Thurber. Sailing from Madagascar in 1685 Thurber and his vessel weathered an Atlantic hurricane en route to their final destination and put into Charleston South Carolina for repairs. Thurber is said to have given Dr. Henry Woodward a store of rice seeds with which Woodward proceeded to experiment. By the time the Moore family relocated from Goose Creek South Carolina to the banks of the Cape Fear River at Brunswick Town in 1725 rice was becoming a major cash crop for Carolina planters. Soon the plantations of the Cape Fear marked the northern-most boundary of the Carolina rice culture. The Carolina Gold strain of the grain grown along the river was said to be so distinctive that one could taste the difference between rice grown on the west bank of the Cape Fear versus that grown on the east bank.

Rice required two things to grow successfully — fresh water and large pools of laborers. The tidal fluctuations of the Cape Fear River made it ideally suited for rice cultivation its freshwater overflow irrigating the young plants via floodgates controlled by slave labor. Indigo silk and later cotton were all cultivated with varying degrees of success along the Cape Fear but until the end of the plantation era after the Civil War rice was king on area plantations.

Slaves made it all work. The plantations the naval stores the rice fields — all depended on the strong backs and hands of the Africans who built the houses and outbuildings tapped the longleaf trunks to collect their valuable sap and tended the fragile young rice plants that became the bedrock of the Cape Fear s plantation economy. By the 1660s slavery was big business. Records show John Vassall dealt in slaves evidenced by a bond between Vassall and his son-in-law Nicholas Ware of Virginia for the services of four Africans. It is almost inconceivable that such men used to a world in which chattel slavery was an integral part would have come to a virgin wilderness like the Cape Fear in the mid-17th century without slaves to help with the heavy lifting of founding a colony.

By the Revolutionary War Cape Fear plantations provided some of the most ardent patriots of the struggle for independence. Cornelius Harnett dubbed the Samuel Adams of the South was master of Maynard (later Hilton) Plantation where the City of Wilmington s main water treatment plant is located today. Major General Robert Howe a hard-drinking womanizing Cape Fear patriot became the highest ranking Southern officer in Washington s Continental Army made his home at Howe Point on the west bank of the river below Brunswick Town. When redcoats occupied the city in 1781 they came armed with blanket pardons for locals who would swear fealty to King George III. The only exceptions: Harnett and Howe whose zeal for rebellion made them most-wanted men.

Greenfield Park with its lake and plentiful azaleas is the site of Dr. Samuel Green s colonial plantation of the same name. The lake s spillway along Carolina Beach Road marks the spot where until the 20th century the plantation s mill existed. Wild rice still grows along the railroad tracks west of the lake evidence that the plantation stretched all the way to the river.

Wild rice grows all over the lower Cape Fear from Wilmington and Bellville to Southport. To passersby on Eagles Island traveling between Wilmington and Leland the remnants of the old rice fields probably resemble marsh grass or cattails.

It was on Eagles Island that first Joseph Eagles then later the state grew the grain. Eagles plantation earned the island its name. The State of North Carolina operated the prison plantations Bleak House and Osawatomie on the island by the turn of the 20th century using convicts to harvest the crop that was still profitable as long as cheap labor was available. Slavery ended in the Cape Fear in 1865 but prison work gangs made up for the absence on Eagles Island until such modes of punishment and rehabilitation went out of vogue.

The planter class formed an oligarchy that ruled the Cape Fear from the very beginning. Wilmington s rise might be attributable in part to the fact that controversial colonial governor George Burrington lost his bid to acquire property north of the city near Castle Hayne to the Moore family (who already owned 115 000 acres of the Cape Fear by 1735). In a fit of pique the governor eventually voided all of the Moore family land patents on the east side of the river and declared that court proceedings would be held at New Town (later Wilmington) rather than Brunswick. The move marked the beginning of Brunswick Town s 50-year decline seeing the first permanent settlement on the Cape Fear become a ghost town by the time British troops landed there in 1776.

A century later a new war threatened the way of life embraced by the planters of the Cape Fear. Plantations along the river saw soldiers in gray erecting great earthworks to protect the port city that would become so vital to the Confederacy s hopes between 1861 and 1865. Slaves who normally worked area rice fields and tar kilns were diverted by military edict to shovel sand at Fort Fisher Fort Anderson and other military constructions in the Cape Fear District. The planters did not like it but they had little choice in the matter.

When Admiral David Dixon Porter s great Union fleet first assembled off New Inlet on Christmas Eve in 1864 and began the bombardment of Fort Fisher Sarah Chaffee Daisy Lamb the Rhode Island-born wife of Fort Fisher commander Col. William Lamb watched transfixed with fear from the back lawn at Orton Plantation. Daisy wrote of watching the shells burst over the sand fort downriver while her husband made his stand with an undermanned garrison.

After Fort Fisher fell a month later blue-jacketed federals began the march up both banks of the river to capture Wilmington. Along the way they put many of the region s plantations to the torch. Orton survived because Yankee doctors chose it to serve as a hospital for their wounded.

When slavery ended so too did the business model that made plantation agriculture possible. Plantation owners on the Cape Fear tried to make a go of it for the next 40 years but slowly the houses and lands fell into disrepair. Parcels were sold off and subdivided. Others succumbed to fire and vandalism. Fields were left to become overgrown reminders of past glories. New owners often from the North bought the near-derelict properties and turned them into hunting preserves and places where they dabbled at being planters. The Civil War ended not just slavery but also the society it supported.

Orton Plantation remains the best example of Cape Fear plantation heritage. Perhaps it is only fitting as Roger Moore s grand home was among the first such edifices along the river. Roger Moore Bacon a descendant of the original Orton owner has begun efforts to restore the house grounds and rice fields to their colonial splendor. It is a renaissance of sorts a tribute not just to Bacon s Moore family predecessors but also to the great estates that played such an integral part in making the Cape Fear what it is.