On the Fast Track

A Wilmington runner has a dream of Olympic proportions

BY Mary Margaret McEachern

Sometimes in life we have the good fortune to meet someone so extraordinary, so inspirational, that we cannot help but be transformed.

Angela Downey, a running coach, personal trainer, lifestyle coach, and elite athlete, is such a person. Her extraordinarily positive personality inspires all who have the privilege to train under her, or simply be in her company. Her gentle encouragement coaxes athletes and others to give their best throughout the most challenging workouts and throughout life.

Downey, a Wilmington native, is training with hopes of competing in the 200-meter and 400-meter sprints at the 2028 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

Sprint events often hinge on a fraction of a second, making qualifying for the Olympics difficult for any athlete, especially one like Downey, who will be 40 when the next Games take place.

Competing in sprint events at an elite level takes raw talent, but it’s the hard work and strict discipline required to prepare for such an extraordinary feat that most find impossible to attain.

Growing up on a waterway at the end of a dirt road on property her family has owned since the 1800s, Downey began swimming at age 2.

Her parents are Charlene and Willie Purvis.

“My parents held the belief that, living so close to the water, I had to know how to swim,” she says.

She also ran.

“Angela has been running since she was maybe 3 years old. Everywhere she’d go, she’d run,” says her great aunt, Addie Bonsignore. “If she was going from the kitchen to the living room, she was going to run.”

She began gymnastics at age 4 and trained in taekwondo between 4-8, earning a purple belt as an 8-year-old.

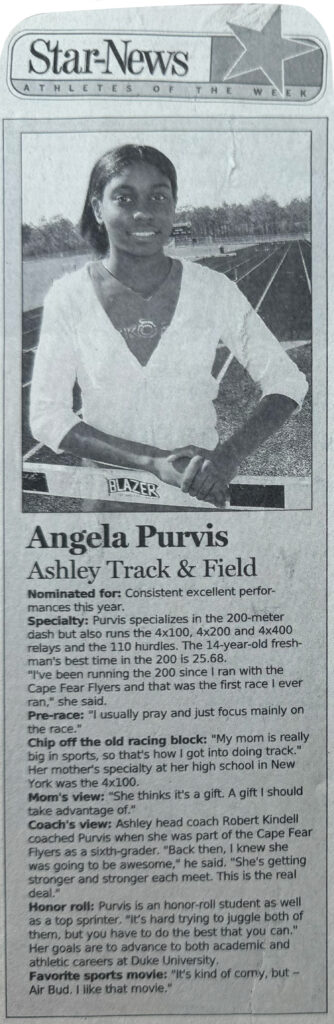

Downey has run competitively for the past 30 years.

“When I started, I joined Cape Fear Flyers, a group that trains youth. I was their only sprinter,” she says.

Running fast is in Downey’s veins.

“My mom used to watch me run down my cousins on their bikes. I could beat them. I then determined that my bike was simply too slow, and I gave it away,” Downey says. “My family sent me running to get supplies. I didn’t think of it as a workout.”

Medaling followed.

“I ran the 100-meter, 200-meter, 4×100-meter relay, 4xw200-meter relay, and 110-meter hurdles events, and I won the Junior Olympic Regional Championship in every event,” she says.

Runners tend to fall into one of two categories: sprint or distance. Rarely can they compete in both disciplines. Downey is an exception.

Primarily a sprinter during her earlier years, she eventually segued to middle distance races, beginning with a 5K (3.1 miles).

“It was my longest run ever,” she says.

Ever the overachiever, she then set her sights on a 50K (31 miles) ultramarathon. She ran her first, the Southern Tour Ultra, seven years ago.

“I had not run even one half or full marathon beforehand. I went straight for the ultra,” Downey says. “Sixteen weeks of training is all you need to do anything. I ran between 60 and 70 miles per week, which far exceeded my sprinter’s wheelhouse.”

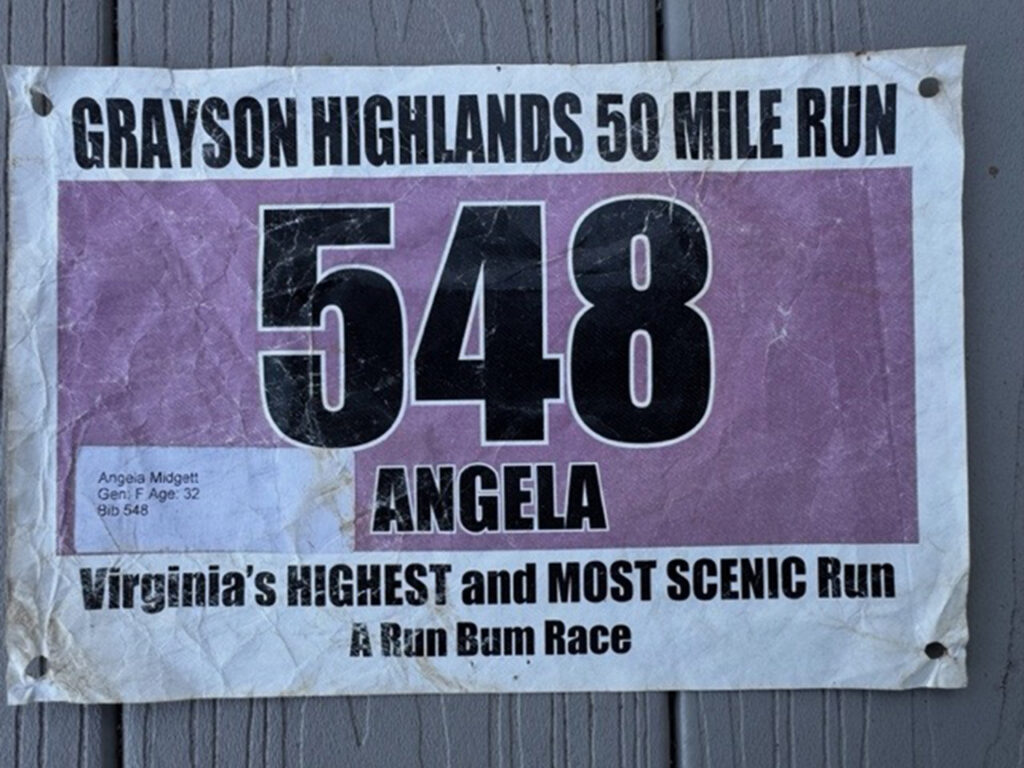

Her next ultra was a 50-miler at Grayson Highlands State Park in Virginia. The race features 9,500 feet of elevation. The terrain can be rocky. Racing such a distance as a flatlander was no small feat.

She did several more ultras, but never forgot her first running love.

“I always will be a sprinter,” she says.

Sprints are highly specialized, with much riding on simply getting a good start.

“It’s all fast-twitch, explosive training, and it’s all about that start,” she says.

Five weeks into her training in October 2024, she knew she needed to concentrate on strength.

“It requires a lot of body weight work from the ground, with big arm movements, and locomotive animal flow,” she says. “I do lots of stair climbing on stadium stairs, and lots of hill work. Range-of-motion in the hip flexors is crucial, so I work on that every day, every chance I get. My training starts at 2 a.m. almost every day.”

She runs sprints two days per week. The training consists of lots of fast intervals, like 16×50 meters progressing from 75 percent to 90 percent effort. The entire workout takes only 20 minutes.

The 200- and 400-meter events demand an extraordinary amount of explosive strength, and a good deal of endurance.

“The 200 is my specialty, but the 400 is a brand-new beast,” Downey says. “With two curves rather than one, the staggered start can be confusing.”

Running 400-meter repeats at top anaerobic capacity is among the most excruciating workouts an athlete can endure.

“If you run it right, you’re almost blacking out at the end,” she says. “When I won the state championship, I actually did pass out. I had to be carried off the track. I had run 12 races that day.”

Downey’s hopeful Olympic journey starts with U.S. Masters Class competition in June 2025, when she will run her first sprint race in more than 20 years. Her confidence is high.

“Gabby Thomas won the [2024] Olympic 200 meters in 21.83 seconds. My goal for that first Masters meet is in the 23-second range,” she says. “This seems like such a small gap, but for sprints this is a huge deal.”

Downey describes running that fast as “feeling like you’re flying.”

“You must have the fastest leg turnover possible and run light,” she says. “In sprints, you literally are flying.”

Coaching came naturally to the lifelong athlete.

“I coach Without Limits distance runners, and I work as a lifestyle, nutrition, and accountability coach for a multi-million-dollar company, working directly with over 200 women throughout the country,” she says.

One of her runners, Alicia Williams, describes Downey as a powerhouse.

“When we do practices on Tuesdays, she starts each of the groups,” she says. “My group will probably be a quarter of a mile into the run and she’ll come blasting by. She’ll be sitting there waiting for us at the end to get our times. It’s like she’s shot from a cannon.”

Downey also works part-time at an athletic specialty store and a real estate office. She has developed a coaching app that provides fitness, mobility, nutrition, athletic mindset, and running gait training.

Even with all that going on, there is still time for her family.

“My husband, Brett, is the reason I can do all of this. He is my hero. He is a professional soft tissue and medical massage therapist, and he helps me immensely,” she says.

Along with daily training, proper rest, nutrition, and massage are crucial to injury-proof the body.

Downey is mother to three children, Trinity, born when she was 16, and sons Nevaeh and Austin. They attend practices and help coach.

With so much going on, planning is huge.

“As a mom, you don’t have a lot of time to take care of yourself,” she says. “My husband really helps me because he’s always watching out for me. He was the first person to invite me to nap during the day. You simply must take time for yourself.”

Downey hopes to stay 90 percent injury-free but says she must be prepared for at least one injury.

“Most sprinters train on already broken bodies before they make it to their goal competition. Injury prevention is as important as the training itself,” she says.

Williams knows about running on broken bones, having snapped her thigh bone running the Boston Marathon in 2016. Three surgeries followed.

“When you have had an injury, you have to be careful. She always encourages us to stretch and rehab that stiffness or injured area. She’s phenomenal with that,” Williams says. “She’s fascinated by the way the body moves in motion. She’s done a lot of independent study.”

Last year Downey pursued certifications in strength, stretching, manual manipulation of muscle groups, relaxation, and run gait analysis.

“Our daughter is the definition of standing in the gap to help others get where they need to go in life. She is a supporter by nature and leads others with love,” says Willie Purvis.

Downey has inspired so many on her incredible life journey. She will continue to inspire others as she embarks on her epic Olympic quest.