Living with Water

The Battleship North Carolina’s low-lying location on the Cape Fear River means the grounds are prone to flooding

BY Simon Gonzalez

The Battleship North Carolina’s low-lying location on the Cape Fear River means the grounds are prone to flooding.

It’s an experience common to many residents and visitors. You want to spend a day at the Battleship North Carolina, but there was a storm in the past couple of days. Will the ship be open? Is the parking lot flooded?

The area around Wilmington’s popular tourist attraction and living history museum is notoriously swampy. High tides and heavy rains can leave the parking lot squishy at best and closed to traffic at worst. It has always been a problem to a certain extent but has increased exponentially in recent years.

“In the first couple of years I was here it really was not an issue,” says retired Navy Capt. Terry Bragg, who became executive director of the Battleship North Carolina in 2009. “We have a 500-space parking lot and there would be a little bit of flooding here intermittently. But in 2015 I really took note of what was happening. Originally it was just occasional flooding. Now it was significant flooding. It was roads, our parking lot. And it was killing our heritage oak trees. It was affecting business operations. During certain times of the year, we would have just general flooding.”

Bragg launched an analytical study to verify what he saw happening. The results were staggering.

“In the ’40s there would be six flooding events in a decade,” he says. “A flooding event is 5.5 feet above mean low water. Even when Hurricane Hazel hit it only caused four flooding events in four days where the tide was higher than 5.5 feet above mean low water. It was really not an issue. If you jump ahead to the decade between 2010 and 2020, there’s 200 flooding events. So, between the ’40s and 2020, there’s a six thousand percent increase in flooding events. Most every month we were experiencing more flooding events than eastern North Carolina received from Hazel. That’s amazing.”

It had evolved from more than an occasional annoyance for visitors to something that could have a devastating economic impact on the decommissioned warship berthed on the Cape Fear River.

“We’re an enterprise business of the state of North Carolina,” Bragg says. “That means that we are 100 percent receipts funded. If I can’t get customers to the battleship to tour or shop in our store, we go to zero. I’ve got employees, I’ve got inventory, we’ve got this national historic landmark to take care of.”

The problem came to a head in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence in 2018. The slow-moving storm dumped more than 25 inches of rain in less than 48 hours.

“Literally our entire parking lot was underwater,” Bragg says. “We’re talking about one to three feet for days and days. There was no opportunity for the Cape Fear River system to absorb all that flooding, which was completely different than Hazel. We’re in a new age.”

A new age calls for new solutions. After Florence, Bragg began soliciting bids from engineering and architectural firms to fix the flooding issues. Raleigh-based Moffatt & Nichol earned the job with an environmentally conscious proposal. Work was scheduled to begin in December 2023 and take eight months to complete. Sometime in the summer the flooding problems should be no more.

The project was dubbed Living with Water. It conveys the idea that Bragg and his staff are not just stewards of an important piece of history. They are also stewards of the environment.

“My job is to run the business of the battleship,” Bragg says. “But my undergraduate degree is in biology from Appalachian State. Our development director has a master’s degree in landscape design. We are a very sensitive environmental conservation group. That’s why we took the path we did.”

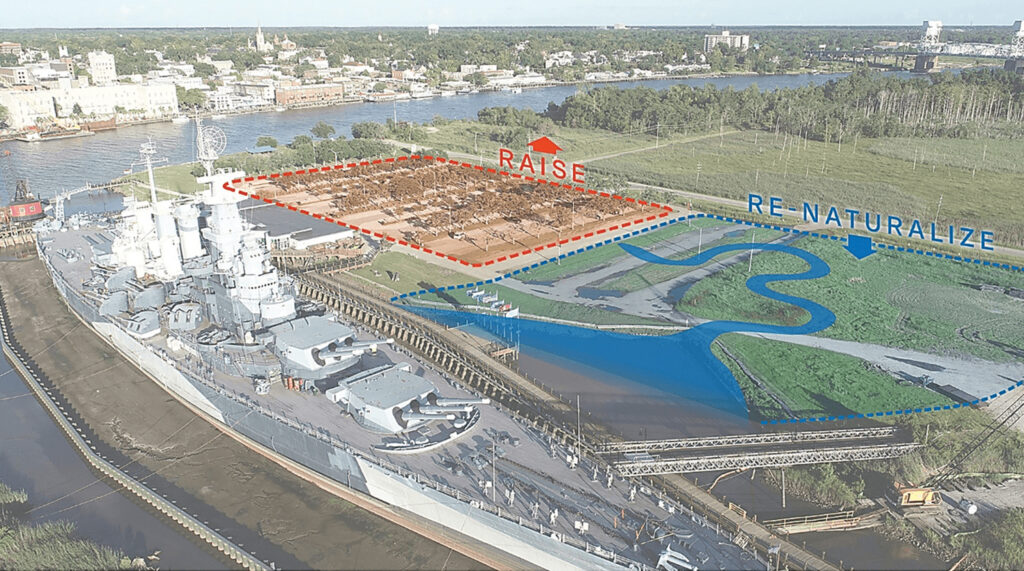

The work will include three primary components: a natural berm, new wetlands, and the elevation of a portion of the parking lot.

The berm, or living shoreline, finds inspiration in Wrightsville Beach’s efforts to keep the tides at bay.

“Wrightsville Beach has expanded on the idea of living dunes and sea oats,” Bragg says. “It keeps the sea back. Every community that has gone with sandbags and hardened structures, it eventually fails. Wrightsville Beach is one of the premier beaches on the East Coast because of their strategy. Well, we’re facing a similar thing. We don’t do sea oats over here at the battleship, but we will build this natural berm, an elevated surface that will keep the river water on one side and our business on the other side.”

Even with the berm providing a natural boundary, some water will always find its way onto the low-lying property, from heavy rain or migrating from elsewhere on Eagle Island. That will be addressed by a new wetland habitat divided by a tidal creek. The wetland will help absorb high tides, while the tidal creek will direct water to the Cape Fear River.

“We are creating a path for the water to flow off,” Bragg said. “Instead of flooding half of our parking lot it will be directed to essentially a living channel.”

The new wetland does come with some tradeoffs. It will take up two acres of the existing parking lot and eliminate a couple of hundred spaces.

“It’s a concern,” Bragg says. “We’re going from approximately 500 parking spots to 300 parking spots. But the 500 parking spots are theoretical when 200 parking spots are not really available anyway because there’s water there.”

The third element of the project is to physically elevate the rest of the parking lot by two to three feet to raise it above what is projected to be the flood zone over the next 15 to 25 years.

The battleship received several bids when the project was advertised but Moffatt & Nichol was the only company to submit a proposal that dovetailed with the conservation-minded goals. That’s an indication this solution is something new for the area.

“In 2018, when we took our needs to the marketplace, all the engineers wanted to use sort of the same template: build hardened features to solve flooding at the battleship,” Bragg says. “Everybody but Moffatt & Nichol. It showed that the concept is foreign to this region. In this area and on the North Carolina coast, there’s very little activity to mitigate flooding. It took us a year to get our CAMA environmental permit approved. It should have taken us three months. But they had never in recent memory had anybody who applied for an environmental permit to take developed property back to its wetland. It took extra research and support to justify what we were doing.”

The battleship might be the first in the area to construct wetlands as a major component to mitigate coastal flooding, but it likely won’t be the last. Outreach efforts during and after construction will open the project to others interested in studying the methods. The public will be able to learn about the work through boardwalks and signage that will describe the natural improvements and plantings.

“We made it an element of our Living with Water project,” Bragg says. “We have a partnership with NOAA. We have a very active partnership with UNCW so they can use our project to teach university students. We want to test techniques and share it with other industries and businesses in eastern North Carolina. We want to share the message because it’s just part of what we do.”

Even with the ongoing flooding issues, the battleship just had its most successful year since coming to the Wilmington riverfront in 1961. Some 232,000 visited the ship during the fiscal year that ended on Sept. 30. Those numbers could grow when a flooded parking lot doesn’t deter attendance.

“We’re just trying to be the good stewards on the property we own,” Bragg says.