Honoring Our Fathers Part II

BY Pat Bradford

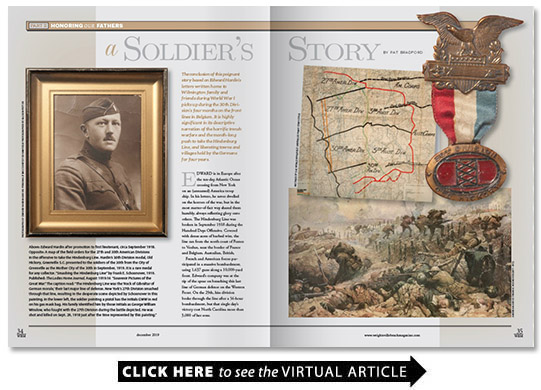

A Soldier’s Story

The conclusion of this poignant story based on Edward Hardin’s letters written home to Wilmington family and friends during World War I picks up during the 30th Division’s four months on the front lines in Belgium. It is highly significant in its descriptive narration of the horrific trench warfare and the month-long push to take the Hindenburg Line and liberating towns and villages held by the Germans for four years.

Edward is in Europe after the ten-day Atlantic Ocean crossing from New York on an (unnamed) America troop ship. In his letters he never dwelled on the horrors of the war but in the most matter-of-fact way shared them humbly always reflecting glory onto others.The Hindenburg Line was broken in September 1918 during the Hundred Days Offensive.Covered with dense acres of barbed wire the line ran from the north coast of France to Verdun near the border of France and Belgium. Australian British

French and American forces participated in a massive bombardment using 1 637 guns along a 10 000-yard front. Edward’s company was at the tip of the spear on breaching this last line of German defense on the Western Front. On the 29th hiss division broke through the line after a 56-hour bombardment but that single day’s victory cost North Carolina more than 3 000 of her sons.

The Hundred Days Offensive

The letters presented here are out of sequential order as written but in order of the events as they unfolded.

The first letter in Part 2 of Edward Hardin’s “A Soldier’s Story” contains a detailed description of the start of the battle of the Hindenburg Line. Part 1 of the story can be found in the November 2019 issue of Wrightsville Beach Magazine.

Oct. 3 1918

This five-page letter was written on plain white paper to Edward’s father.

You all will have to pardon my silence of several day’s duration for I’ve been just about the busiest young man in France for the past week or so. I wish I could tell you all where I’ve been and what I’ve been doing but possibly you have read in the papers of the breaking through of a hitherto impregnable portion of the Hindenburg line recently — well! I was right there — in fact the whole company was “there with bells” and what we did to poor old Fritz was a plenty. My Soul! It was wonderful but at the same time it was the most horrible sight I’ve ever seen. The attack started at daybreak and lasted well into the afternoon and if ever anyone wishes for a taste of Hell I can heartily recommend an attack as a good sample. But it was an entire success and we have been the recipients of many congratulation — the whole Division did marvelously well. But it’s the aftermath that makes one wonder if it is “worth the candle.” When the casualty lists are published I’m quite sure that the war will come closer home than ever to the people of Wilmington and North Carolina.We are out of the lines for a well-earned rest now and are billeted in a ruined city. There is not one building left standing in the town which I judge was originally about the size of Raleigh or Durham. We are all living in the cellars which all French houses have and while it is not exactly palatial imagine the relief it must be to get away from being continually shot at and shelled at.

Edward’s letters often included tidbits of leave time experiences and interaction with locals. Others contained the responses to questions posed in previous letters by family members or responses to news of friends births sicknesses college marriages and deaths. In addition to his parents he wrote to his siblings nieces and nephews always encouraging them in whatever endeavor they were occupied in including younger half-brother John Haywood Hardin Jr. who had begun attending the University of North Carolina the same school that Edward was “asked to leave” after his first year.

Nov. 25 1918

From a 10-page letter written to John Haywood Hardin Jr.

I am delighted to know that you have gotten over the natural homesickness and have settled down to enjoy college life. It is “kinda” rough on a fellow those first few weeks away from home isn’t it? I can remember as well as anything how I used to wish I was home again and think that there never was a more lonesome sight than that old campus but one soon learns to love it and actually long to get back again when away from it.

Good intentions with me are very similar to Boche counterattacks — you can never tell when they will materialize. I have intended writing you ever since you left for Chapel Hill but it seems that by the time I’ve written home once or twice a week all my spare time has been used up… our Division was in the midst of a huge attack which lasted from September 29th to Oct 20th and believe me Buddy that was some fight. We first ran the Boche out of the strongest positions they had on the Western front in the Hindenburg line and take it from me that battle was a “humdinger.” It lasted from dawn till dark and there was something doing every minute of the time…

On our Divisional front we had ninety-six machine guns laid for barrage and a piece of artillery (ranging from 18 pounders to 8 in. Howitzers) for every ten yards of front. About midnight a runner came around that zero hour would be at 5:50 A.M. so we went to the Artillery nearest us and synchronized our watches. At 5:45 every gun was loaded laid and checked and every gunner standing with his finger on the trigger waiting for the corporal who had his eye glued to the watch to give the signal to “commence firing.” Precisely at 5:50 those thousands of pieces of artillery and all the machine guns opened up and honestly it sounded as if “all Hell had busted loose.”

At one second before 5:50 there wasn’t a sound except an occasional shell screaming overhead or a burst of machine gun bullets whizzing past but at one second after 5:50 you couldn’t hear yourself think. Our gun positions were in a little trench on top of a ridge and from there I could see the whole battle. First it looked as if the whole world were going up in clouds of mud dirt etc. where the shells were hitting. After a three minute standing barrage the Infantry started the advance under a creeping barrage and it was certainly interesting and at the same time horrible to see the dough boys get up from the ground where they had been lying on their faces and start forward with the tanks which in the meantime had gone forward under the cover of the barrage. One could see a squad or a platoon start forward walking as if out for a stroll and suddenly some fellow would crumple up and lay still or another throw up his hands and fall backwards or still another stumble and fall with a bullet or piece of shrapnel in his leg and crawl off to a shell hole and squat down to wait for the stretcher bearers. In the mean time I was having trouble enough of my own … we were in a trench with our guns mounted on the parapet and Jerry evidently had this trench taped for no sooner had our barrage opened up than he laid down a counter barrage with artillery and M.G.’s. right on our trench. Well I have been caught in some pretty heavy shell fire since I have been over here but never in my life have I ever seen anything to equal that. Of course we were right in the open trench and it is miraculous to me how any of us got out alive. I was commanding a battery of six guns and had to keep going from one gun to the other and was expecting every step to be my last but really at the time I didn’t think of that. One time I was caught in a bay between two streams of M.G. fire the parapet had been blown down on either side of the bay and “Jerry” had one gun shooting thru’ one side and one thru’ the other so there was nothing to do but squat down and wait until he shot one of his belts out which I did and then made a run for it and had gone about twenty yards when a whiz bang bursted on the parapet and a piece of shrapnel hummed by my face and clipped a little nick in my nose. Well when I finally had a chance to reckon up I found that I had had three guns knocked out and had lost only twelve men.

Capt. Gause was away at the time at school so I was commanding the Co. and believe me I had my hands full but finally succeeded in getting all my wounded to an Aid Post and the dead put in a sheltered place until we could get a chance to get them buried then we sat and waited for orders…

After two days rest his company moved forward again. This portion of the letter to the younger Hardin describes the liberation of towns held by the Germans and first mentions his hospitalization.

So we were not ordered forward until two days later and then we caught H— again. We drove the Boche back steadily for ten days and liberated the towns of Premont Bohain Busigny Bellicourt Brancourt St.Souplet Mazinghein and many other smaller villages all of which had been held by the Germans since 1914.

There were thousands of civilians in these towns who have been held captives and you should have seen them greet us when we came through chasing Fritz. It was on the night of Oct. 17th that my cellar was blown in and I got knocked out. I was sent in to the Aid Post and after getting treated felt so much better that I went on forward and rejoined the company and stayed with them until they were relieved on the 21st. I was so sick by that time with the combination of German gas and influenza that I couldn’t make the hike back with the Company so had to go to hospital…

The “Ole Hickory” Division has certainly made a name for herself over here and we’re all mighty glad to belong to it. We have been cited in official orders on several occasions. On the whole our Company has been fairly fortunate. Out of a fighting strength of 98 men and six officers we have gone through four months of active service on the front and have lost only two officers and about forty men. Many of the companies which went in with fighting strength of from 150 to 250 men came out with one or two officers and between 15 and 50 men.

Hospitalization and War’s End

Oct. 17 1918 Edward was hospitalized he had previously mentioned cuts and bruises to hands and feet earlier in the conflict almost as an afterthought.

Oct. 24 1918

From a letter to Edward’s parents explaining his care in a British base hospital “Somewhere in France.”

You can’t imagine how wonderful it is to be lying up in a big comfortable bed entirely out of the sound of the gun after a week of living in little niches cut out in the banks and constantly always dodging shells. I am one of the very few Americans in this hospital so I am known all over our ward as “the big Yank in No. 7”.

Whenever I think of all that has happened in the past ten days the whole seems invested with an atmosphere of absolute unreality and I again thank the good Lord that I am still alive and able to write. Goodness! what a period it has been in my life – the first six days a horrible nightmare and the last four (since I have been in the hospital) a wonderful dream. It all started just exactly ten days ago. We were ordered to get ready at once to go up the line and our orders were to first put up a barrage and then go over the top with the Infantry. Well we got to work picked our positions dug the guns in figured the data and laid our guns and then sat back to wait until zero hour (Fritz was shelling us pretty heavily all the time and we lost four or five men). Capt. Gause and I had taken up our headquarters in a cellar in a little village very close to our guns and were sitting around with several of our headquarters men waiting for the zero hour. As usual Fritz was shelling the village heavily with gas and H. E.s. Suddenly bedlam broke loose and when I came to a few seconds later our cellar was literally blown to pieces — my orderly was completely buried and several others hurt but miraculously none of them seriously. I was hit in several places by flying bricks and other debris and got a slight overdose of gas but after a trip to the Aid Post I felt much better and went on back to the Company and then we started — for five days and nights steady going with never a rest — attack after attack. Our bunch fought like demons and although it cost us quite a number of men we kept Fritz on the run and gained our every objective but gosh! it was grilling work. When we were finally relieved we were practically exhausted and then orders came that our transport which was ten miles back would have to be brought up before morning and it fell to my lot to go after it so I spent the entire night in the saddle. Rode 20 miles in a driving rain over trails and mud tracks and roads with no slicker and as a result here I am in a base hospital with a beautiful case of “flu.”

Nov. 1 1918

From a letter to his father from a convalescent hospital at Trouville France.

“I suppose Turkey’s surrender and Austria’s capitulation and request for an armistice were received with wild joy in the States. It certainly looked good to us over here and it’s bound to be the beginning of the end for I can’t see how Germany can last much longer at the rate we have been driving them recently and the enormous numbers of prisoners guns ammunition etc. we have captured. They can’t last much longer. Why on this front alone the past three months we have captured 172 659 prisoners 2 378 pieces of artillery 17 000 machine guns and over 2 750 trench mortars also enormous quantities of ammunition stores supplies etc. Gosh! won’t it be great when old Kaiser Bill does finally discover that he is licked good and plenty and “throws up the sponge.”

Edward returned to duty three days prior to the signing of the Armistice the Nov. 11 1918 cessation of hostilities on the Western Front. The Treaty of Versailles was signed the following June taking force on January 10 1920.

Dec. 2 1918

This excerpt is from a three-page letter on plain white paper written in pencil to Edward’s father.

We didn’t hear the news of the armistice until about 10:30 A.M. the morning of the 11th and we just refused to believe it then. It seemed too good to be true and not until it had been verified officially by Division Hdqrs. would the men believe and then about the only expression of sentiment one could hear was a deep sigh of relief and “Gosh! I wonder how soon we’ll get home?”

While there’s no denying the fact that all of us are mighty glad it is all over still I believe that many of us ‘way down in our hearts regret the fact that we will never get a chance to strike at Germany in her own land. I notice that several of the papers state that the American soldiers are fraternizing with and befriending German prisoners but that certainly is not the case with our Division for I have never seen a bunch hold so whole souled a hatred for any person or anything as our men do the Boche and after having seen some of the things that I have seen I can’t blame them a bit; in fact I find myself experiencing the same loathing and hatred…I sometimes wish that the Armistice had never been signed until Germany was completely wiped from the face of the earth.”

Nov. 11 1918

This is a portion of a five-page letter written in black ink on plain white stationery to his mother on Armistice Day. The 30th division’s name was blanked by censors.

I don’t wonder at all Mama that you all are proud of the ___th Division. They have really done marvelous work and anywhere we go in France and people learn that we belong to “the 30th American” we get a real royal reception. First we broke the Hindenburg line and went ten or twelve miles further and then we got in another big stunt and took every objective under very adverse circumstances. Of course it has been costly — our casualties among the fighting personnel having been well over 50% but then that is to be expected. I was awfully distressed to hear of Frank William’s death. Didn’t know a thing about it until I got back from the hospital. Frank was a wonderful officer and I understand that he was universally loved and respected throughout his entire regiment by both officers and men and would undoubtedly have won a promotion in the near future.

Once the fighting had ended Edward began to write about what he experienced but was still restricted in what he could share.Returning to American soil took far far longer than the men of the 30th imagined. As his company waited Edward expressed a longing for home.

Nov. 15 1918

From a two-page handwritten letter on plain stationery written in green ink to his sister Lauris.

“I am actually awfully unreasonably homesick. But after all I wouldn’t take anything for what I have seen or the experiences that I have had and it’s quite a wonderful feeling to know that one has done his duty to the fullest of his ability and after it all has come out alive from a veritable Hell. How I do hope that this armistice is the end of “things awful” for I’d hate the thought of taking my company into the lines again for it nearly breaks my heart to see man after man many of whom are very close to me “get theirs.” You just can’t imagine what it means dearest mine to see those poor fellows carried off on stretchers silently suffering and begrudging each little groan or moan which escapes them. They are wonderful and I can’t help but feel that I am a much better man for having been associated with such fellows. Those of us who are fortunate enough to return will be fortunate men indeed in more ways than one.

Post War

This proud American hero finally returned to the United States disembarking at Newport News Virginia. He received an honorable discharge April 3 1919.

Sixteen months after his discharge from the Army Edward married Wilmington’s Virginia Farmer. Edward’s story however ends tragically.

He went back to work in his father’s pharmacy but always ambitious he expanded into two pharmacies of his own. He and Virginia had three daughters; his youngest Helen was born the same week the American stock market crashed in 1929.

The struggle to remain viable during the Great Depression overwhelmed Edward. He could not manage the debt on his two stores and lost his house. In 1930 two weeks shy of his 37th birthday this extraordinary survivor of some of the fiercest fighting in the Great War took his own life.

Virginia lived to 104 and is buried beside him in Oakdale Cemetery. Their daughter Virginia Hardin Hawfield just celebrated her 98th birthday.

Footnote

Following his retirement in 2007 grandson Ed Hawfield spent over two years collating and transcribing his grandfather’s letters and the obligatory government postcards. He researched and added footnotes and bound everything into a book in November 2011. He moved to Wilmington with his wife Nancy three years later. Ed speaks to interested groups sharing 45-minute presentations of his grandfather’s letters.