C E L E B R AT I N G R E S I L I E N C E

Cinco de Mayo BY GIOVAN J. MICHAEL

Today, Cinco de Mayo is a grand celebration of Mexican food, dance, and culture. Ironically, it

is a much larger holiday in the United States than it is in Mexico. That makes sense considering

the fates and cultures of these two great nations have always been intertwined.

In 1861, the United States and Mexico

were both in crisis. The U.S. was in the

first year of the Civil War, which would

become the bloodiest conflict in Amer-ican

history. After a war for its own

independence from Spain, a territorial

war against the U.S., and a civil war

against its own people, Mexico was in

economic ruin. Both nations were not

only exhausted but vulnerable to foreign

attacks.

Wounds were still healing between the

two countries, but they would soon learn

they had a common enemy in Europe: an

ambitious French emperor named Napo-leon

III. He was the nephew of Napoleon

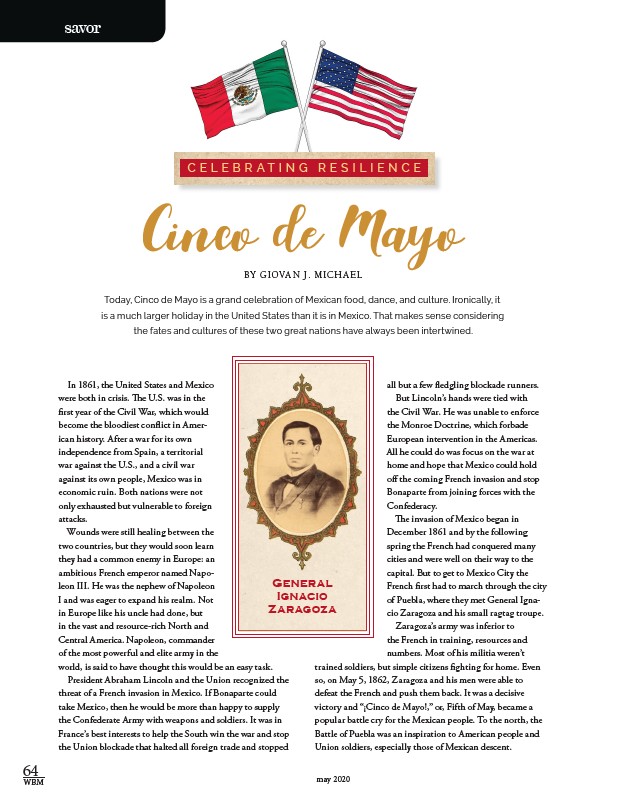

General

Ignacio

Zaragoza

I and was eager to expand his realm. Not

in Europe like his uncle had done, but

in the vast and resource-rich North and

Central America. Napoleon, commander

of the most powerful and elite army in the

world, is said to have thought this would be an easy task.

President Abraham Lincoln and the Union recognized the

threat of a French invasion in Mexico. If Bonaparte could

take Mexico, then he would be more than happy to supply

the Confederate Army with weapons and soldiers. It was in

France’s best interests to help the South win the war and stop

the Union blockade that halted all foreign trade and stopped

64

WBM may 2020

all but a few fledgling blockade runners.

But Lincoln’s hands were tied with

the Civil War. He was unable to enforce

the Monroe Doctrine, which forbade

European intervention in the Americas.

All he could do was focus on the war at

home and hope that Mexico could hold

off the coming French invasion and stop

Bonaparte from joining forces with the

Confederacy.

The invasion of Mexico began in

December 1861 and by the following

spring the French had conquered many

cities and were well on their way to the

capital. But to get to Mexico City the

French first had to march through the city

of Puebla, where they met General Igna-cio

Zaragoza and his small ragtag troupe.

Zaragoza’s army was inferior to

the French in training, resources and

numbers. Most of his militia weren’t

trained soldiers, but simple citizens fighting for home. Even

so, on May 5, 1862, Zaragoza and his men were able to

defeat the French and push them back. It was a decisive

victory and “¡Cinco de Mayo!,” or, Fifth of May, became a

popular battle cry for the Mexican people. To the north, the

Battle of Puebla was an inspiration to American people and

Union soldiers, especially those of Mexican descent.

savor