MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Beauty of Pastels

B y J e s s i c a N o va k

Pastels are pure color with just enough binder to keep

them together for use. They have significant staying power,

and are one of the most pure and permanent forms of art

in existence. Leonardo da Vinci’s works in chalk still survive

500 years after their creation, and Edgar Degas’ vivid pastels

of ballet dancers still delight us 150 years later.

The word pastel comes from the medieval Latin word

pastellum, or paste, referring to the binder that’s a main

ingredient in the art medium. Pastels are made with a color

or pigment, plant sap or other binder, and water. They

are soft enough to adhere to a textured surface, but hard

enough so they don’t fall apart in the artist’s hand.

Pastels come in degrees of hardness and vary by the

amounts of binder and pigment. The more binder, the

harder the pastel.

Hard pastels are valuable for fine details, while soft and

oil pastels have less binder and are better for blending. Soft

pastels are the most commonly used form. If you make

a mistake, use a hard paint brush outside and dust off as

much as you can, then color over it.

In Deborah Quinn’s Art Methods and Materials class at

Cape Fear Community College, she guides students in mak-ing

their own pastels.

“This is economical, and a way to learn firsthand about

the medium and understanding your tools in making art,”

she says.

For soft or true pastels, Quinn provides the formula, one

part gum tragacanth (binder), 30 parts distilled water, refrig-erate

24 hours. The binder is the paste into which colors are

added. Add chalk and talc (baby powder) to soften the flow

of the pastel and add filler.

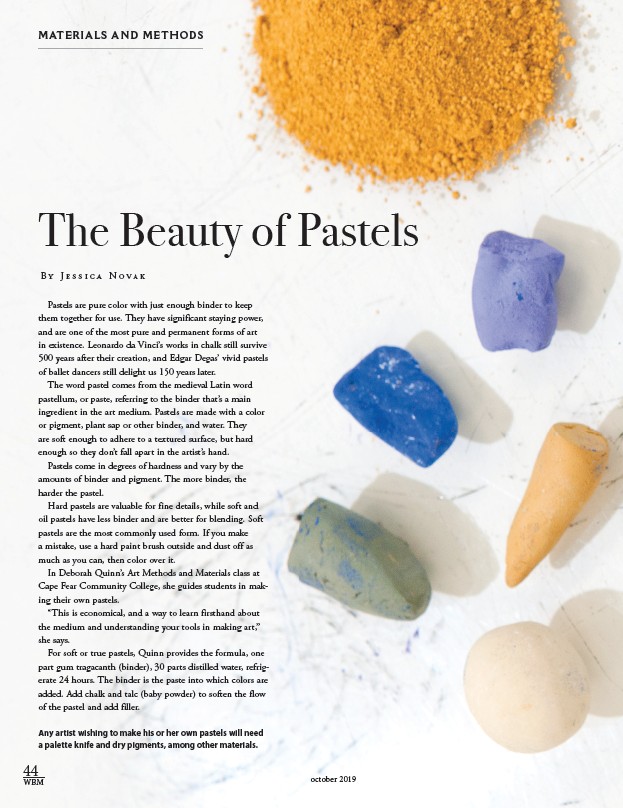

Any artist wishing to make his or her own pastels will need

a palette knife and dry pigments, among other materials.

44

WBM october 2019