PPART OF THE FUN of collecting is learning the provenance

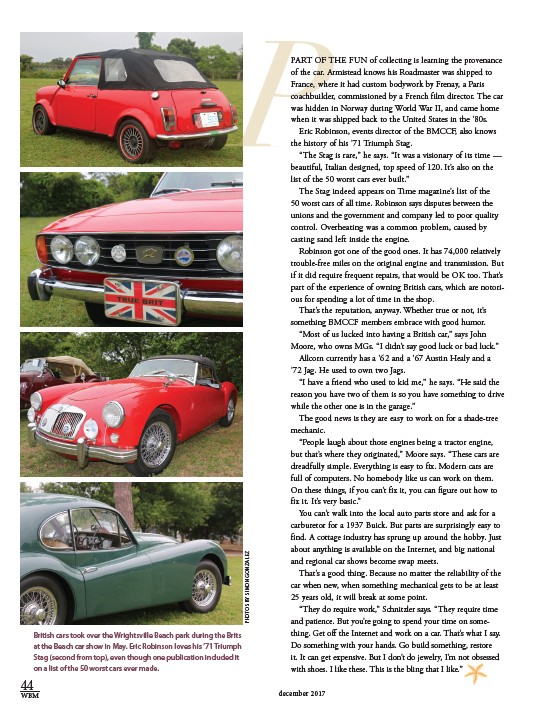

British cars took over the Wrightsville Beach park during the Brits

at the Beach car show in May. Eric Robinson loves his ’71 Triumph

Stag (second from top), even though one publication included it

on a list of the 50 worst cars ever made.

PHOTOS BY SIMON GONZALEZ

of the car. Armistead knows his Roadmaster was shipped to

France, where it had custom bodywork by Frenay, a Paris

coachbuilder, commissioned by a French film director. The car

was hidden in Norway during World War II, and came home

when it was shipped back to the United States in the ’80s.

Eric Robinson, events director of the BMCCF, also knows

the history of his ’71 Triumph Stag.

“The Stag is rare,” he says. “It was a visionary of its time —

beautiful, Italian designed, top speed of 120. It’s also on the

list of the 50 worst cars ever built.”

The Stag indeed appears on Time magazine’s list of the

50 worst cars of all time. Robinson says disputes between the

unions and the government and company led to poor quality

control. Overheating was a common problem, caused by

casting sand left inside the engine.

Robinson got one of the good ones. It has 74,000 relatively

trouble-free miles on the original engine and transmission. But

if it did require frequent repairs, that would be OK too. That’s

part of the experience of owning British cars, which are notori-ous

for spending a lot of time in the shop.

That’s the reputation, anyway. Whether true or not, it’s

something BMCCF members embrace with good humor.

“Most of us lucked into having a British car,” says John

Moore, who owns MGs. “I didn’t say good luck or bad luck.”

Allcorn currently has a ’62 and a ’67 Austin Healy and a

’72 Jag. He used to own two Jags.

“I have a friend who used to kid me,” he says. “He said the

reason you have two of them is so you have something to drive

while the other one is in the garage.”

The good news is they are easy to work on for a shade-tree

mechanic.

“People laugh about those engines being a tractor engine,

but that’s where they originated,” Moore says. “These cars are

dreadfully simple. Everything is easy to fix. Modern cars are

full of computers. No homebody like us can work on them.

On these things, if you can’t fix it, you can figure out how to

fix it. It’s very basic.”

You can’t walk into the local auto parts store and ask for a

carburetor for a 1937 Buick. But parts are surprisingly easy to

find. A cottage industry has sprung up around the hobby. Just

about anything is available on the Internet, and big national

and regional car shows become swap meets.

That’s a good thing. Because no matter the reliability of the

car when new, when something mechanical gets to be at least

25 years old, it will break at some point.

“They do require work,” Schnitzler says. “They require time

and patience. But you’re going to spend your time on some-thing.

Get off the Internet and work on a car. That’s what I say.

Do something with your hands. Go build something, restore

it. It can get expensive. But I don’t do jewelry, I’m not obsessed

with shoes. I like these. This is the bling that I like.”

44

WBM december 2017