Eagles Island

The small island across from downtown Wilmington is rich in history

BY David A. Norris

Eagles Island occupies a unique place in the lower Cape Fear. It is perhaps most famous as the home of the USS North Carolina, yet the island’s long history includes abundant ricefields, naval stores production, and shipbuilding.

The island, up to two miles across and seven miles north to south, is bordered by the Cape Fear River, the Northeast Cape Fear, and the Brunswick River to the west. It is also sliced by Alligator Creek and Redmond Creek.

Most of the island is within Brunswick County. A narrow portion across the Cape Fear River from downtown Wilmington, including the home of the USS North Carolina, belongs to New Hanover County.

The island’s configuration has changed over the centuries. A 1906 soil map of New Hanover County shows it as a cluster of several closely packed islands separated by creeks and streams. Many of these streams are no longer visible in satellite views.

On John Ogilby’s 1672 Map of Carolina, prepared for the Lords Proprietors, Eagles Island was called Cranes Island. Another early name was Buzzard Island. The current name dates to about 1737, when King George II granted most of the “big island” opposite the new town of Wilmington to Richard Eagles.

The site of Wilmington, on the east side of the Cape Fear River, was atop relatively high ground. Across the river, Eagles Island was much lower. Although less suitable for habitation, the swampy low ground was easily adaptable to growing rice.

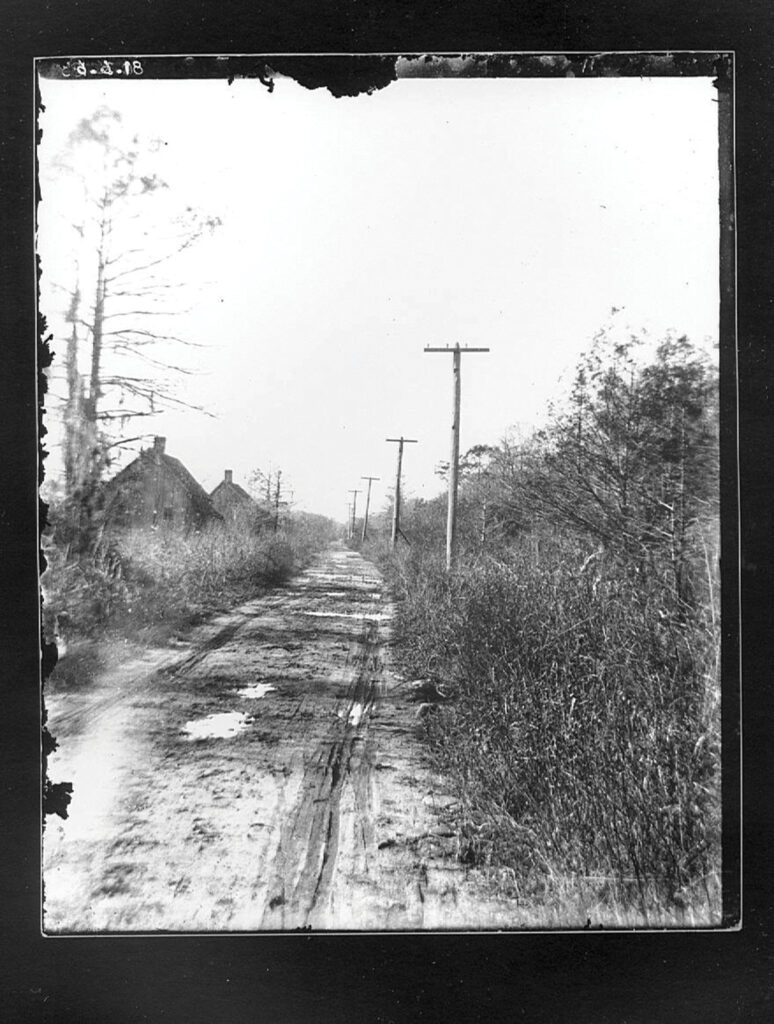

Soon after Wilmington was settled in the 1730s, ferry boats carried travelers from the town to Eagles Island. From there, another ferry crossed the Brunswick River to Brunswick County. The road forked near the landing, with one route running northward to Cross Creek (Fayetteville) and the other past Brunswick Town and into South Carolina.

Ferries were typically flatboats. A bar across the bow kept horses from jumping into the river, and a bar across the stern prevented vehicles from rolling backwards off the deck. The flatboats were often towed by a boatman in a rowboat.

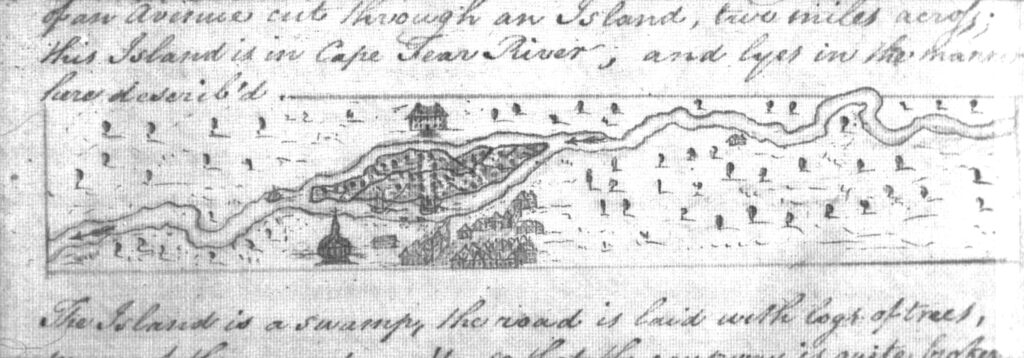

In the late Colonial era, the King’s Highway connected the Northern colonies with the South. The worst section from South Carolina to New England was said to be the swampy route along Eagles Island.

Richard Dry was given permission to construct a causeway across the island in 1764. The eastern end was opposite the ferry landing at the foot of Market Street. From there, the causeway ran across the island, ending at the landing of the Brunswick River ferry. Work continued for years, and was eventually picked up by Dry’s son-in-law, future North Carolina Governor Benjamin Smith.

The causeway was sometimes under water from high tides or storm surges. Hugh Finlay, a postal inspector, wrote in 1771 that the road “is laid with logs of trees, many of them are decay’d, so that the causeway is quite broken and full of large holes, in many places ’tis with difficulty that one can pass it on foot, with a horse ’tis just possible.”

In Colonial times, Eagles Island was primarily used for rice cultivation. The flat, low terrain was ideal for a system of canals, dams, and dikes to irrigate and flood the fields.

Industry began to replace rice growing in the early 1800s.

In 1841, a turpentine distillery on Eagles Island caught fire. A fire engine from Wilmington was taken across the river but could do little against the ferociously burning and highly flammable turpentine and rosin. Glowing sparks wafted across the river and set fire to the roof of a warehouse near the Wilmington waterfront.

Some 150 feet from the burning distillery was an old wooden building used as a powder magazine. The magazine had already had one close call in 1839. Lightning struck the schooner Eliza Jane, shattering the foremast. Giant splinters were hurled against the powder magazine, but no harm was done.

Wilmington merchants wary of fire kept a small amount of gunpowder in their stores and paid to store the rest of their explosive inventories on Eagles Island. Shopkeepers grumbled about paying the storage fee of 12 ½ cents per keg, not to mention a 50-cent tip every time a laborer took a gunpowder keg to or from the magazine. The building was notoriously insecure; it was easy for a thief to break in and make away with kegs of powder. The practice of keeping gunpowder on Eagles Island, away from downtown, continued for decades.

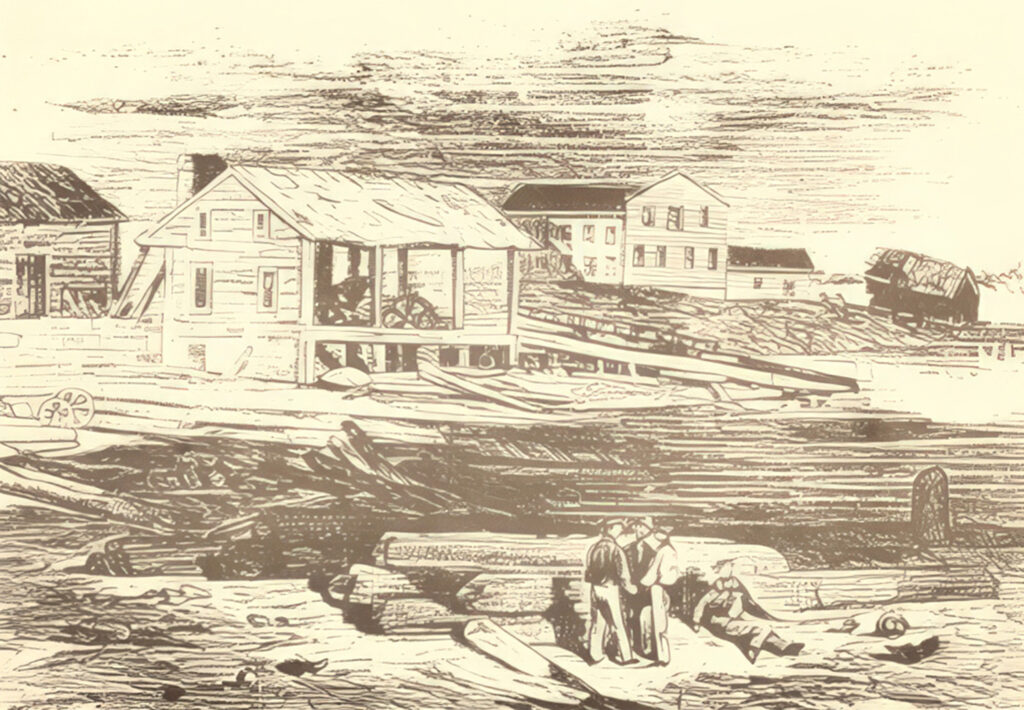

Samuel Beery and Sons purchased a steam sawmill just south of the causeway in 1848 and opened a shipyard there as well. The yard built a brig and a schooner in the next couple of years.

Samuel’s son, Benjamin, bought him out in 1852. By that time the property included a marine railway for ship repair, a rigging loft, and a blacksmith shop.

Completed in 1853, the Wilmington & Manchester Railroad linked the Cape Fear region with South Carolina. The eastern terminus was on Eagles Island. Tracks ran across the island and crossed a new railroad bridge across the Brunswick River. From there, the tracks ran to Manchester, South Carolina, where passengers could change trains for Charleston and other towns.

Plans to run the tracks over the old causeway were dropped, and the railroad chose a new route a short distance to the north. To transfer passengers and freight, the steam ferry General W. W. Harlee ran between Eagles Island and Wilmington.

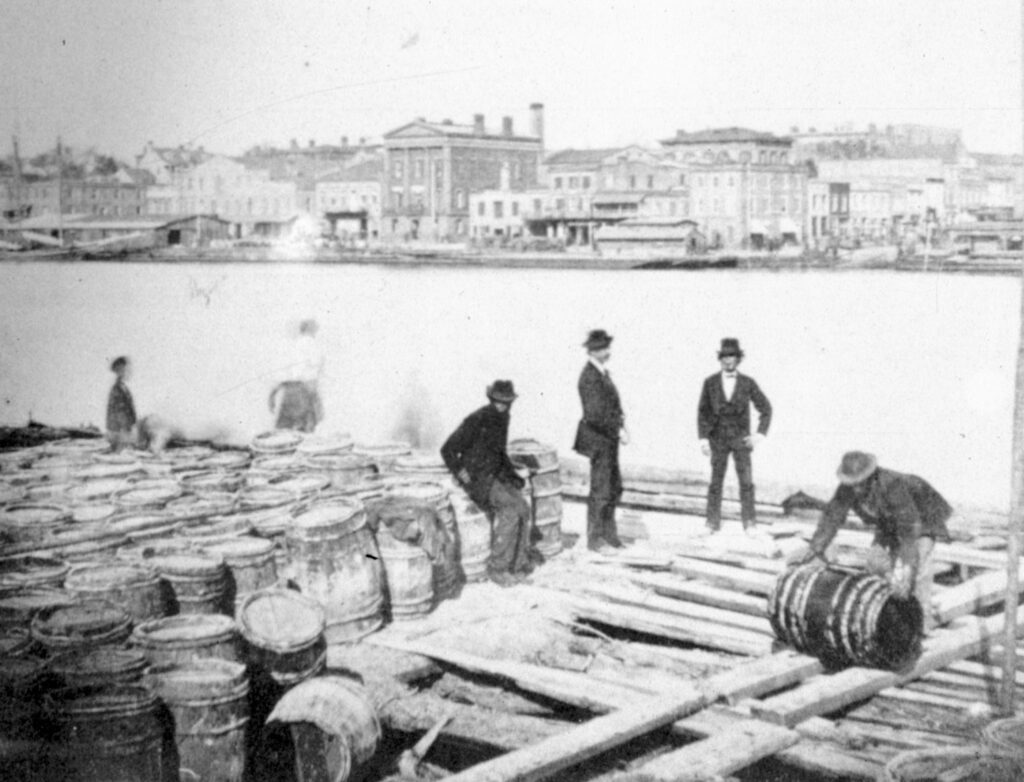

During the Civil War, blockade runners tied up at wharves on Eagles Island to load cotton bales. A steam cotton press tightly compressed cotton into bales so more could fit aboard the ships.

A spectacular blaze broke out in a warehouse on the industrialized portion of Eagles Island about 12:40 a.m. on April 30, 1864. The blaze spread quickly until “the whole western bank of the river for several squares was one line of flame.” Wharves along a ¼-mile strip were consumed, along with over 4,000 bales of cotton, 25 railroad cars, the office of the Wilmington and Manchester Railroad, part of the Beery Shipyard, including its sawmill, a rosin oil works, and numerous warehouses and sheds. The Daily Journal estimated the losses at around $6 million.

Another massive fire was set on Eagles Island on Feb. 21, 1865, when the Confederate Army evacuated Wilmington. Benjamin Beery’s shipyard and other waterfront industrial sites were destroyed, as was the railroad ferry and the partially built ironclad CSS Wilmington.

In 1869, new railroad bridges crossed the Northeast and main branches of the Cape Fear River north of Wilmington. Trains could now pass directly through Wilmington, bypassing Eagles Island. The old Wilmington & Manchester Depot and the tracks on Eagles Island were abandoned. Ferries continued to take passengers and freight from the foot of Market Street to the industrial district of Eagles Island.

Rice production continued after the Civil War. In the late 1800s the state of North Carolina leased two plantations, Bleak House (south of today’s Cape Fear Memorial Bridge) and Osawotomie (across the Cape Fear from Greenfield Lake), for use as prison farms. In 1895, a letter in the Southport Leader claimed that two-thirds of the island’s 3,300 acres were under cultivation.

Rice production shifted to Louisiana and Texas in the early 1900s. Eagles Island rice was still regarded as high quality, but only a small quantity was grown as seed rice. One of the later newspaper references to rice-growing came in 1917, when a car ran off the Eagles Island Causeway and came to a stop in a ricefield.

Traces of canals, dams, and dikes constructed to aid rice farming still survive on the island.

In the 1800s, people in downtown Wilmington would annually hear gunshots coming from Eagles Island toward the end of August. This marked the annual arrival of ravenous flocks of bobolinks, otherwise known as rice birds. During their migrations, thousands descended on the ricefields. Men, women, and boys guarded the fields, some firing blank charges to scare birds away with others firing live ammunition.

Hunters wandered the ricefields as well. Weighing only one ounce or so, the birds were regarded as a delicacy. They sold for 20 to 50 cents per dozen. Several Wilmington restaurants had rice birds on their menus, sometimes served on toast or with a sauce made with Madeira wine. The birds also were shipped as gourmet treats to restaurants as far away as Charlotte.

Fire remained a great peril on Eagles Island, including one that caught the attention of the Wilmington Sun on March 22, 1879.

“The wind carried ashes from the burning grass on Eagles Island and distributed them in showers over the city all day yesterday. That they call a ‘Brunswick snowstorm.’”

Except for a short-lived fire company established on the island in 1871, blazes were handled by loading a Wilmington fire engine and crew onto a flatboat and towing them across the river. Tugboats and steamers helped by pumping river water onto waterfront fires.

Industry continued to grow. The Acme Tea Chest Company of Glasgow, Scotland, opened a factory in 1899 that shipped planks and veneer to Scotland, where they were made into tin-lined tea chests.

With so much activity and without a bridge from Wilmington, ferry service was important. In 1902, the Brunswick Bridge and Ferry Company charged five cents for each person, draft animal, and wheel of a vehicle. Thus, a wagon driver paid 35 cents each way to get from Brunswick County to Wilmington.

In 1907, a 30-foot gasoline-powered boat that could carry 15-20 passengers began service. A tow rope pulled a flatboat loaded with wagons or cars. By 1920, the New Hanover-Brunswick Ferry Commission provided a public ferry service. The 80-foot John Knox made round trips from the foot of Market Street to the Eagles Island landing in 30 minutes. A larger boat, the Menantic, was added in 1924.

In 1929, two new bridges crossed both branches of the Cape Fear River. The John Knox remained in service until it struck a piling by the island and sank in 1937.

The old Beery Shipyard was acquired by the Wilmington Iron Works in 1911. The new firm built the Wilmington Marine Railway in 1912. The railway could haul vessels of up to 2,000 tons out of the water for repairs.

A pair of wooden schooners, each 238-feet long, were begun at the Wilmington Iron Works yard in 1916. In preparing the yard, which was across from Dock Street, workers demolished “an old vine-covered brick chimney,” a remnant of the Confederate cotton press used during the Civil War.

One of the schooners, the Hauppauge, was launched soon after the U.S. entered World War I in 1917. It was torpedoed the next year by a German U-boat. The second schooner, the Commack, was launched in 1918 and lasted until it was wrecked off Sandy Hook, New Jersey in 1925.

The property was bought by R. R. Stone in 1924, operated as the Stone Marine Railway until a fire in 1946.

After World War II, the U.S. Navy maintained a “mothball fleet” of hundreds of decommissioned Liberty ships and other cargo vessels in the Brunswick River. Officially called the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, Wilmington, the number of vessels peaked at 437 in 1949-1951.

To make room, the Corps of Engineers widened 3 ½ miles of the Brunswick River, creating a basin 1,200 feet wide. The ships were tied up on both sides of the river, on Eagles Island, and on the mainland.

Hurricane Hazel slammed the mothball fleet on Oct. 15, 1954. Several ships broke loose when their mooring cables snapped. Three drifted northwards with the heavy winds, pushed toward the Brunswick River bridge and, according to newspaper accounts, a 100,000-volt power line. Tugboats stopped them by nudging them aground shortly before they smashed into the bridge.

One Liberty ship, the Howell E. Jackson, was stuck on the western shore of Eagles Island more than three months later. Finally on Jan. 8, 1955, with the efforts of three tugboats, the ship’s engine, and a high tide, the ship was freed.

Some of the reserve ships were called up for service during the Korean and Vietnam conflicts. Most were never needed, and they were sold or scrapped. The last ship, the SS Dwight W. Morrow, was towed away in 1970. Even today, if you drive across the Brunswick River Bridge on U.S. 74 and look to the south, you’ll see the river widen a couple of hundred yards downstream. That’s the upper reach of the basin dug for the long-gone ships.

Like the mothball fleet, the marine railways, docks, warehouses, factories, and working vessels clustered on Eagles Island are mostly gone. Ruined pilings and bulkheads mark the locations of docks and industrial sites.

One of the most memorable events of Eagles Island’s long history came in October 1961.

Donations from people across the state had saved the World War II battleship USS North Carolina from being scrapped. The North Carolina Battleship Commission purchased 36 acres on Eagles Island as a permanent home for the ship. The land was near the old Wilmington & Manchester Railroad Depot. Workmen digging a slip turned up an enormous number of old railroad spikes.

It took 11 tugboats and two days of maneuvering to get the ship’s massive hull (at 729 feet, the ship was longer than the Cape Fear River is wide at that point) pushed into the spot where it’s still on display.

A great place to see a panorama of Eagles Island’s historical remnants and natural beauty is the Wilmington Riverwalk. Along the island’s shore is an array of iron boilers, steam engines, and other Victorian and early 20th-century machinery from tugboats and steamers. Weathered wooden pilings mark nearly vanished docks and wharves between the bridge and the battleship site.

A lavish growth of marsh grasses and trees rises from abandoned ricefields, shipyards, sawmills, and turpentine distilleries. Once noisy with the clattering of shipbuilders, buzzing sawmills, steamboat whistles, and busy dock workers, today one might see pelicans, egrets, or herons flying over the quiet marshes and woods between the USS North Carolina and the Cape Fear Memorial Bridge.