Drum Fishing on Hutaff Island

Going to Hutaff Island was never just a fishing trip — it was always an adventure

BY Robert Rehder

HUTAFF ISLAND, Spring, 1970

The word “remote” didn’t come close to describing the island. There was no bridge, no ferry, no road, and no people. The only direct water passage was a shoal-studded, oyster-rock ribbon of water known as Elmore’s Inlet that withered to a ditch at low tide. A shallow draft, bateau-style boat running a high tide was the only way to get there.

It was never easy, but if you could pick your way through a thousand acres of salt marsh, find the secretive inlet, and somehow get to the north shoal of Hutaff Island, you were in one of the greatest red drum fishing spots on the North Carolina coast.

The welcoming parties were ospreys, snakes, sharks, giant stingrays, loggerhead turtles and roving clouds of mosquitoes. The only paths on the island were narrow game trails made by deer, rabbits and raccoons.

Massive dunes rose like pyramids from the undisturbed beach, protecting a maritime forest of oak, wild cherry and myrtle. Mourning doves came in droves to roost in the oaks, and marsh rabbits played in the wild blackberry patches. Iconic beauty tinged with an eerie loneliness was the island’s persona.

The fishing was superb, but whether you fished or not, just being on Hutaff’s north beach where the wind blew wild through the ancient spit of forest and giant waves rolled and thundered in the surf was a rare and unforgettable experience — the kind that burns in one’s memory.

To get to the beach you first had to find the inlet. Old charts dating back to the 1800s labeled it Old Topsail Inlet, but the locals who fished there knew it as Elmore’s Inlet, or simply Elmore’s. It formed the northern boundary of Hutaff Island, which was then a little-known barrier island off the coast of Pender County some seven miles north of Wrightsville Beach.

Islands such as Hutaff are separated from the mainland by extensive salt marsh and miles of tidal creeks interspersed with wooded hammocks, home to roosting birds, otters, minks, the occasional deer, alligator, and other itinerant visitors.

Riddled with shoals and sloughs, Elmore’s was a mystical, raveling passage that weaved through a maze of cordgrass and Spartina marsh. Laced with spectacular reefs and bars that stretched out into the nutrient-rich Atlantic, the area provided an essential destination for an adventurous band of red drum fishermen who often camped and fished there.

The conflagration of marsh, ocean and inlet formed a vibrant ecosystem that annually produced a swath of fish, crabs, shrimp, oysters, clams and mussels. At falling tide a smorgasbord of marine life flowed out to sea, drawing a mix of game fish to the food-rich outer lumps and shoals.

At certain times, tides and moon phases, huge red drum, North Carolina’s state saltwater fish, joined the hungry mix.

Red drum, also known as channel bass, are known for their coppery color, distinctive black tail spots, and drum-like sound the male makes. Adult drum are magnificent creatures that can live as long as 50 years and have an average weight of between 40 and 50 pounds, though some scale much larger.

While these big game fish primarily stay offshore, on full moons in spring and fall they sometimes visit shoals and sloughs around remote coastal inlets and barrier islands, foraging in the shallows for crabs, shrimp and finfish. The north shoal of Hutaff Island at Elmore’s Inlet was just such a place. It held massive fish, many visible for sight casting.

Getting there, however, and returning to the mainland safely was another matter. The island was difficult to access in anything but a jon boat. However, shifting winds and strong currents could render a small boat quite vulnerable, so the voyage was always a gamble for even the most seasoned fishermen and lent a mysterious aura to the island.

Hutaff had many moods. Calm and lovely by morning, sudden storms could turn it wild, fierce, and trackless by nightfall. Fishing could be fantastic one day and frustrating the next. The inlet was so profuse with marine life that drum had all the live bait they wanted floating right past their noses. Fishermen with artificial lures and day-old mullet often found it hard to compete.

Treacherous currents and rip tides challenged even veteran fishermen and kept most away. The result was a relatively peaceful, undisturbed red drum fishery — a top secret location frequented by only a few.

One of those few was Mike Merritt, Harbor Island native, co-founder of Atlantic Marine at Wrightsville Beach, and for many years an avid red drum fisherman. Merritt immersed himself in the sport, researched tactics, and talked to veteran drum experts while constantly learning about tackle and techniques.

Merritt and his fishing friends had a traditional meeting with the big drum each year.

“We camped and fished on the north end of Hutaff Island every spring on the full moon in May,” Merritt says. “The big drum were skittish, and if you made noise with a boat or anchor chain, they would leave the slough and you’d never see them again. So we were quiet, and slipped in there usually by moonlight and fished the falling tide. The average fish was 44 to 50 pounds.”

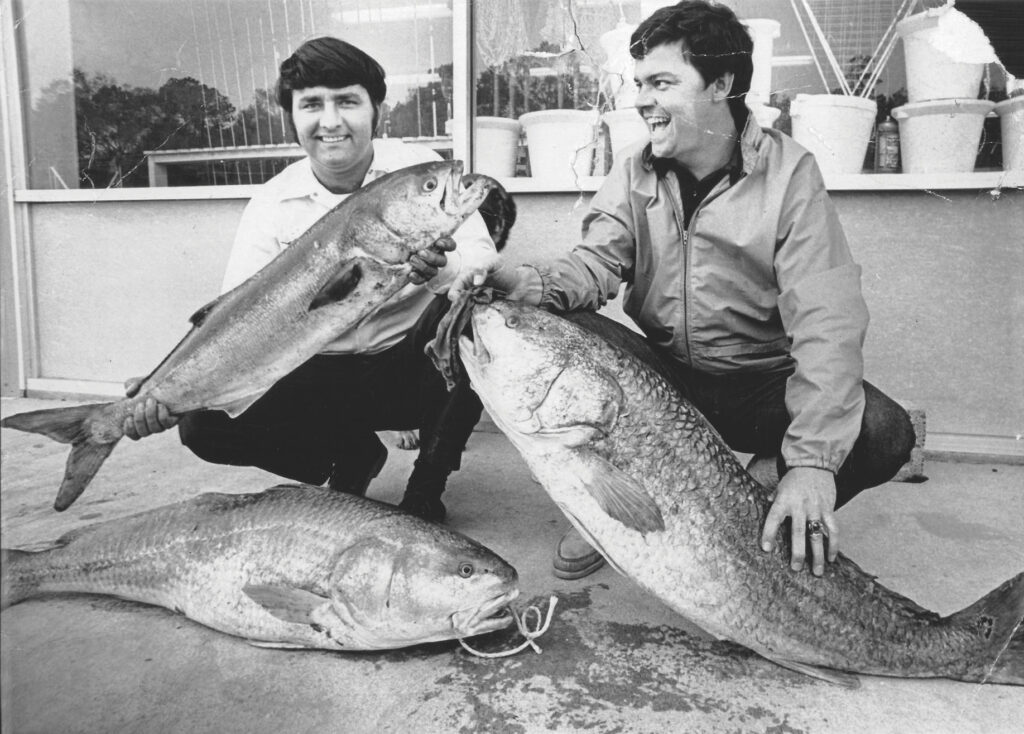

Kit Taylor, another veteran drum fisherman, recalls many trips to Hutaff. He scoured the islands for drum and often fished at night. While camping and fishing at night at Elmore’s Inlet on a fishing trip in 1972, Taylor landed a 54.5-pound drum, a New Hanover Fishing Club record and the largest caught on a rod and reel during the club’s history.

“From our base camp in a wooded grove on the island’s north end, we fished the surf usually at night or at dawn on falling tide. That’s when fishing was best,” Taylor says. “The gear was usually a large, 9-foot Harnell rod with a Penn Squidder reel loaded with 30-pound monofilament and cut mullet for bait. Sometimes we used a Mitchell 302 spinning reel and a lure, but the majority of the time we used mullet as bait. We always fished the sloughs, which could be right there at the inlet or hundreds of yards south. You just had to find them. We looked for water 12 to 16 feet. There was no set area — just wherever the sloughs were deep and there were rips and bottom structure.”

In an article on drum fishing, the late George Canady, a respected veteran fisherman who frequented the island, wrote in the 1951 New Hanover Fishing Club Annual, “You will find fishing best on the last of the low tide, slack, and the first few minutes of the rising tide, late afternoon and better yet at night around the inlets as they come in from the ocean feeding.”

Occasionally, one of the crew received a call from their friend Hall Watters after an aerial view from Watter’s spotter plane showed a school of red drum off the island. Watters was a pilot for the Southport menhaden fleet, but being an active drum fisherman, he kept a sharp eye along the coast for the big fish. Weather permitting, he would often land his plane on the strand and commence fishing. Watters is credited with first catching big drum on a surf plug known as the Porter Pirate “62”, a wooden, cigar-shaped lure that could easily be cast long distance.

“Hall Watters was interested in more than just catching fish,” Taylor says. “He was a collector of drum lures and tackle and an expert in surf fishing. He really knew all aspects of red drum fishing — the tackle, the tides, and the sloughs. He knew what red drum liked and he matched tackle to the target.”

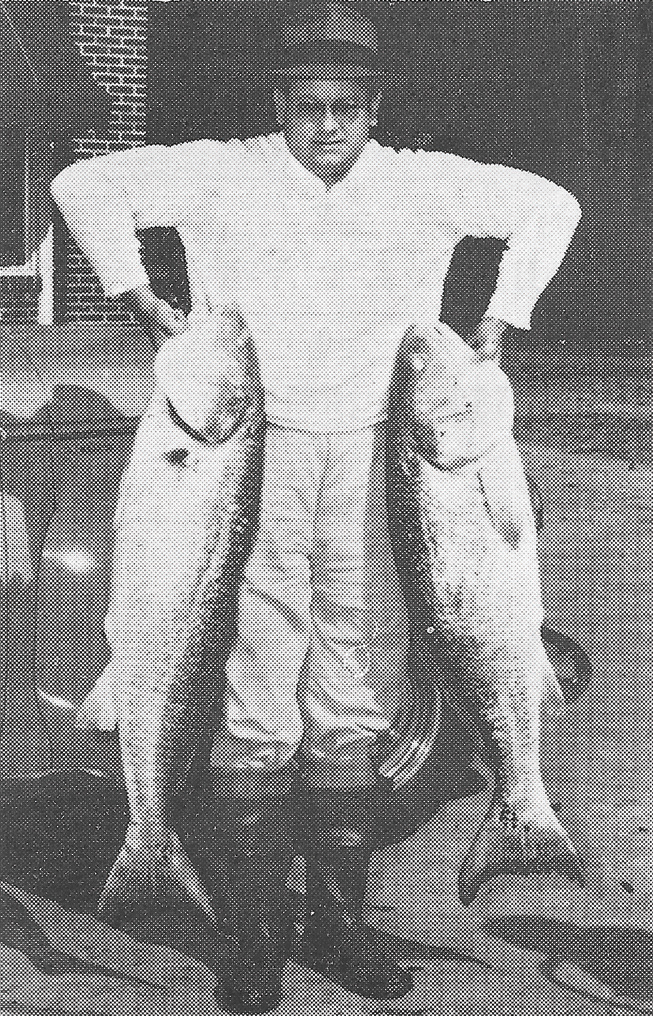

The men routinely landed 40- to 50-pound drum, the photos of which appeared in the New Hanover Fishing Club Magazine of that era. The fishermen were quite popular and many angler friends, in hopes of similar luck, would press the group for vital information. Typical of successful drum fishermen, the responses, if any, were few and seriously inaccurate.

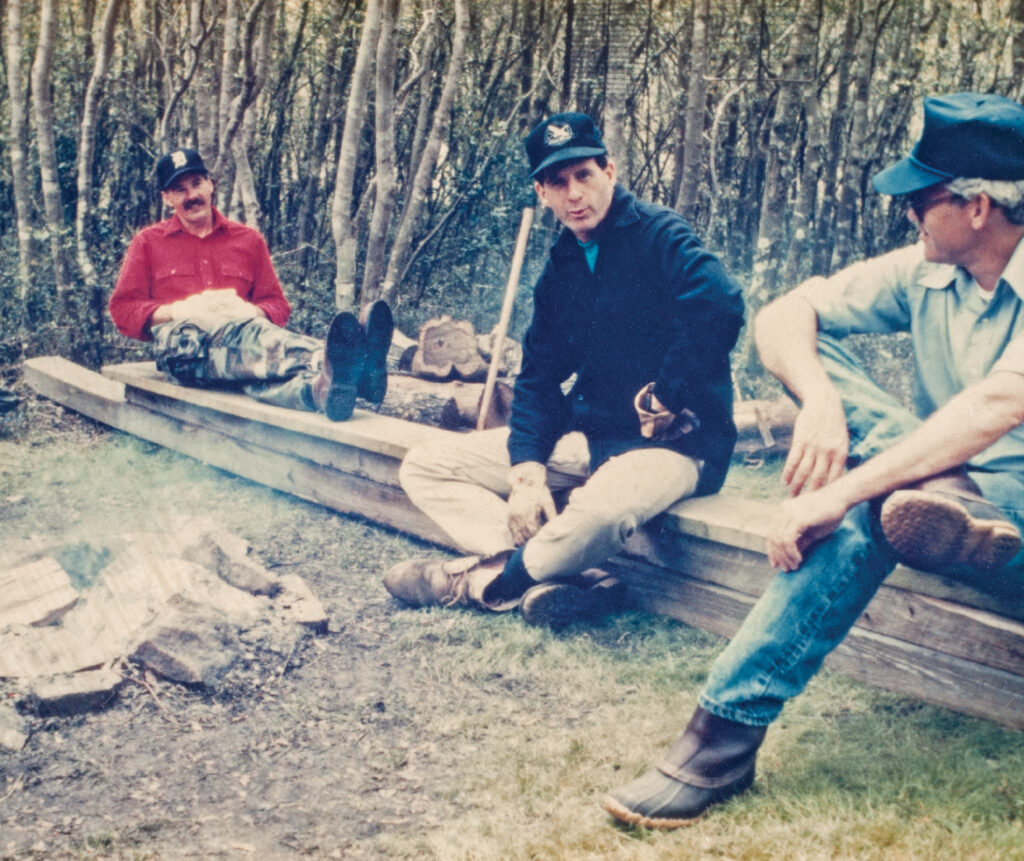

A typical spring camping and fishing trip might happen like this. After a few hours of sleep, tucked back into the dunes in warm sleeping bags, two fishermen, who had arrived during the night, stirred in the cool, gray light of dawn. Pale embers from their evening campfire glowed in the morning mist.

A smoky red sun rose slowly from the depths of the sea as doves, wrens and larks began to call from the forest nearby. Raucous terns, skimmers and oyster-

catchers worked the shoreline. Marsh hens clucked and squawked. A squadron of tundra swans flew over high, their eerie calls echoing down the strand.

Out in the sloughs, gulls wheeled and dove into a school of pogies, a favorite finfish of red drum. The fishermen awoke suddenly, scrambling to rig their big rods with long leaders, 4-ounce sinkers, and single 7/0 hooks threaded through a slab of cut mullet. They waded out into the surf slough, breathless as cold, salt spray peppered their faces. Breakfast could wait. They were after big fish, and they didn’t care about much else.

Once in the slough, the fishermen paused, positioned their surf rods behind them. In a smooth arc, the first fisherman cast his bait high in the air out into the depths where the gulls swooped and circled. It didn’t take long. A massive tug followed by the whine of a sizzling drag, and the rod bent into a deep curve.

The second fisherman cast, and a minute later his rod suddenly lurched down, twisting into a dangerous bend, the reel singing a high-pitched howl. A feverish battle ensued as it always did with rod-and-reel fishermen battling red drum.

When an angler hooked a drum, care was taken to carefully play the fish or a torrid run could spool a reel, stripping off the last bit of line. If the drag was too tight, the friction could seize the drag, rendering the reel useless. Worse, the shock and run of a 50-pound drum could occasionally shear off the rod tip or an eye, or even break the rod into splinters.

Even if all went well with their gear, the fishermen constantly struggled for footing in the deep, shifting sloughs and fought both wave and current while arms tightened and backs ached.

“There was really nothing like it,” says Tripp Brice, who was raised on Topsail Beach and fished on Hutaff Island most of this youth. “If you have ever had the privilege of drum fishing and hooked a big one, you know the sheer excitement of testing yourself and your gear against one of the strongest fish in the ocean.”

It’s usually all a weekend fisherman can do to land a 10-pound puppy drum on a stout spinning rod. Think about a 50-pounder and a fight that may last half an hour! All of the angler’s experience comes to bear, as well as each screw, pin and eye of his gear, any of which could buckle, break, crack, shatter or implode at any minute — and often did.

A hooked drum starts with a series of freight train runs out to sea that can easily strip off 100 yards of line. The big fish can then turn on a dime and commence a scorching reverse run leaving your heart pounding as you feverishly reel to gain slack line while the drum beelines straight for you. Then, while you untangle the resulting bird’s nest in your line, the fish rolls, reverses direction again, tail-swats your already frayed line, and then pulls another switchback!

Taylor has experienced multiple drum battles and knows the grueling sequence quite well.

“The worst is when they go to the bottom and try to grub out the hook while all the time your rod is whiplashing and your drag whining,” he says. “When they do that, the hook usually comes out and you lose the fish.”

More than half a century has passed since drum fisherman roamed Elmore’s Inlet and the secluded sloughs along Hutaff Island. In those days, anglers could bring their fish to shore and proudly pose for the traditional picture. Today’s regulations limit recreational anglers, and most fishermen now are strict catch-and-release advocates.

When Hurricane Floyd closed Elmore’s Inlet in 1999, Hutaff became contiguous with Lea Island and now is known as Lea-Hutaff Island. Fishing remains excellent at times, especially at Topsail Inlet to the north and Rich’s Inlet to the south.

Open expanses of bare sand from hurricanes and tidal overwash have compromised the maritime forest, and only remnants of the massive primary dunes exist in a few locations along the island. But camping, hiking and shelling are still popular.

Red drum fishing may never be the same as it was years ago. Nevertheless, the peaceful barrier island still offers a sanctuary for migratory waterfowl, loggerhead turtles, and nesting shorebirds. It continues to support a fascinating and complex marine ecosystem.

The National Audubon Society, the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust, the State of North Carolina, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are all working to protect the island so that it remains a haven for wildlife. A 25-acre area on the northern end was designated a North Carolina State Park named the Lea Island State Natural Area.

If you want to go: A private boat, kayak or canoe is still the only way to get to the island. Most boaters make the trip from the Intracoastal Waterway either through Topsail Inlet, which is the island’s north border, or Rich’s Inlet to the south. Both inlets offer calm mooring in bays behind the island. Exploring the system of tidal estuaries by canoe or kayak is always interesting. Surf fishing is popular especially in the fall, and the backwater creeks and tributaries offer excellent fly fishing for small drum year-round. Several professional fishing guides serve the area. Clams, oysters and small fish are plentiful, but licensing may be required and harvesting is regulated by the state. Rules and regulations can be found at most bait and tackle shops. From April through August, some marked bird nesting areas may be closed to entry.