Colonial Ghosts: The Forgotten Tale of Brunswick Town Part I

BY Jason Frye

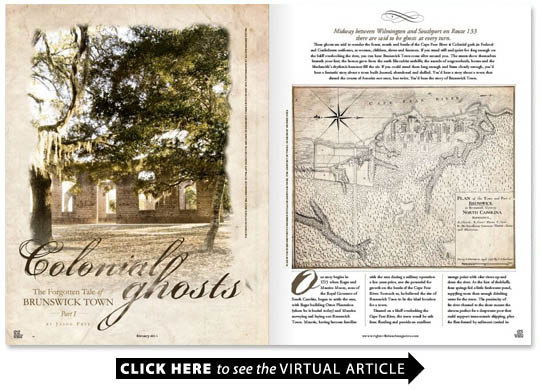

Midway between Wilmington and Southport on Route 133 there are said to be ghosts at every turn. These ghosts are said to wander the forest marsh and banks of the Cape Fear River in Colonial garb in Federal and Confederate uniforms as women children slaves and freemen. If you stand still and quiet for long enough on the bluff overlooking the river you can hear Brunswick Town come alive around you. The streets show themselves beneath your feet; the homes grow from the earth like cubist anthills; the sounds of wagon wheels horses and the blacksmiths rhythmic hammer fill the air. If you could stand there long enough and listen closely enough youd hear a fantastic story about a town built burned abandoned and shelled. Youd hear a story about a town that altered the course of America not once but twice. Youd hear the story of Brunswick Town.

Our story begins in 1725 when Roger and Maurice Moore sons of the Royal Governor of South Carolina began to settle the area with Roger building Orton Plantation (where he is buried today) and Maurice surveying and laying out Brunswick Town. Maurice having become familiar with the area during a military operation a few years prior saw the potential for growth on the banks of the Cape Fear River. So much so he believed the site of Brunswick Town to be the ideal location for a town.

Situated on a bluff overlooking the Cape Fear River the town would be safe from flooding and provide an excellent vantage point with clear views up and down the river. At the foot of the bluffs three springs fed a little freshwater pond supplying more than enough drinking water for the town. The proximity of the river channel to the shore meant the site was perfect for a deepwater port that could support trans-oceanic shipping plus the flats formed by sediment carried in Town Creek prevented further passage up the river. Moore and the first settlers believed the site to be far enough inland to protect it from hurricanes (they were wrong). They also believed it to be far enough upriver to protect it from pirates (wrong again). So in 1726 a handful of settlers established Brunswick Town and began to carve out a life.

By the1730s Brunswick Town was the county seat of New Hanover County and an official port of entry into the colony of North Carolina two positions that made Brunswick Town more important than many towns in the colony. In 1734 Royal Governor Gabriel Johnston who lived in Brunswick Town had a falling out with several prominent families likely over shipping or land and moved the New Hanover County Seat from Brunswick Town to a settlement upriver called Newton (which in five years time would be renamed Wilmington). Newton was also a port town but the shoaling at the confluence of Town Creek and the Cape Fear River prevented large ships from going that far upriver. As a result Brunswick Town despite the loss of power and influence brought on by Royal Governor Johnstons move remained one of the more important ports in the colony and the official port of entry. Both ports were active for decades sending naval stores including tar pitch rope spars masts and turpentine to England from Brunswick Town and to the other colonies from Newton.

Times were treacherous and the war between England and Spain drew Spanish privateers (pirates) to the area to disrupt commercial traffic. In 1748 three Spanish ships entered the Cape Fear River and made their way to Brunswick Town. There they bombarded the town landed and looted. Colonists mounted a successful counter-attack sinking one ship and driving the remaining pair to retreat.

The coming years brought prosperity to Brunswick Town which reached its peak in the late 1750s and early 1760s as shipping traffic in and out of the town increased. Construction began on St. Philips Church in 1754. The church was to be one of the Kings Chapels and act as his voice in this part of the colony. The presence of a Kings Chapel meant Brunswick Town had cemented its role as one of the most important towns in North Carolina.

At its height Brunswick Town had an estimated 250 citizens and more than 60 buildings including a common house with six fireplaces and rooms for merchants and the Royal Governors home Russellborough. In 1758 Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs moved the colonial capital to Brunswick Town from New Bern after he began to feel unsafe there. Governor Dobbs saw the formation of Brunswick County in 1764 and Brunswick Town was named the county seat. In the spring of 1765 shortly after Dobbs death William Tryon became Governor and moved into Russellborough keeping the seat of power for the colony in Brunswick Town. Governor Dobbs was buried in the cemetery of the nearly completed St. Philips Church.

That same year Parliament passed the Stamp Act a tax on paper goods in the colonies including letters newspapers pamphlets wallpaper and wills. The tax was intended to pay for the defense of the colonies and fund the French and Indian War but few here saw it that way. Colonists viewed the Stamp Act as taxation without representation as they had no voice in Parliament.

By January of 1766 Brunswick Town was the center of North Carolinas Stamp Act resistance. Prominent citizens frustrated with British intrusion into business affairs began to boycott British goods and refused to sell or provide any goods to British soldiers or to pay the hated tax. Their boycott was so effective that trade in Brunswick Town ground to a halt sending a strong message to the Crown and its representatives and to the growing ranks of Patriots who were thinking of independence.

On February 16 representatives from the Sons of Liberty a group of prominent New Englanders intent on independence arrived in Wilmington and a local Sons of Liberty chapter was formed. The fight for independence in North Carolina had started.

The new Sons of Liberty chapter was quick to act and on February 19 they marched on Brunswick Town. A group of armed men estimates vary from 150 to 500 surrounded Governor Tryons residence and held him under house arrest for two days.

On February 21 Governor Tryon caved in to the demands of the Sons of Liberty releasing ships and stores held by the British. Tryon William Dry Collector of the Port and William Pennington the Customs Comptroller signed statements agreeing to stop enforcement of the Stamp Act. According to Jim McKee program coordinator at the Brunswick Town State Historic Site it is possible that this was the first armed resistance against British authority in the colonies.

In 1770 Royal Governor Tryon felt so threatened he removed all articles of the King from now completed St. Philips Church including the Bible Kings seal the silver and all items bearing the Kings Crest and moved to New Bern for the final year of his governorship. His move signaled the beginning of the end for Brunswick Town.

By 1775 Royal Governor Josiah Martin felt unsafe in New Bern and fled to Boston. There he met with British High Command and said North Carolina was a divided colony but all he needed to gather a huge army of Scottish Highlanders and other Loyalists and squash the Patriots was supplies troops and the Banner of King George. He convinced the High Command that as word of his army spread Loyalists support him and that once the campaign started more loyalists would join his forces.

The High Command swayed by his argument ordered General Cornwallis to set sail for the colonies with an invasion force. In February Cornwallis and his army sailed from Cork Ireland ready to rout the Patriot militias in the Cape Fear region. Peter Parker did the same leaving from Plymouth with more troops. Their plan was to rendezvous at the mouth of the Cape Fear River and meet Royal Governor Martin and his forces for an assault on the Patriots in the region.

Martin returned to North Carolina to meet his Loyalist army. On the trip South his ship stopped another at the North Carolina-Virginia state line and he invited everyone aboard. At dinner his plans for the massacre of Patriots and the razing of Brunswick Town were revealed to guests. Word spread to the Patriots and by the time Martin reached Brunswick Town only Loyalists remained.

In the meantime storms delayed the British fleets trans-Atlantic crossing putting them a month behind schedule. Word got out of Scottish Highlanders plan to meet Martin and join his army at Fort Johnston (now Southport) and at Moores Creek Patriots ambushed the Scottish Loyalists killing a few and sending the remainder into hiding in the forests and swamps. Many returned home but the dozen or so Scots that did meet Martin arrived a month late.

By mid-March 1776 Martin and his force of 300 led by Captain John Abraham Collett found the Cape Fear thick with Patriots and militia members. They began conducting raids up and down the river burning the homes of known and suspected Patriots. At Brunswick Town in addition to the Patriots homes they burned William Drys home Bellfont formerly Russellborough the Royal Governors residence.

In April the fleet arrived late and with a smaller force than expected. They joined Martin and Captain Collett in their raids and in May Generals Clinton and Cornwallis burned much of Brunswick Town including it is believed St. Philips Church.

Despite the raids Patriots put up stiff resistance and the decision was made to change strategies and instead attack Charleston South Carolina before Fort Moultrie could be completed. Clinton and Cornwallis would then send armies north from Charleston and south from Virginia to rid the Carolinas of the Patriot insurrection. Before they left they burned every home and building within rifle shot of the river from just south of Wilmington to the ocean. Ultimately their plan to rout the Patriots was unsuccessful.

Later that year the North Carolina Congress revoked Brunswick Towns charter due to the dwindling population and the rising prominence of Wilmington. In the late 1780s or early 1790s technology made it possible to dredge the shoals at the mouth of Town Creek which made Wilmingtons port the maritime center and signaled the end of 18th century Brunswick Town where only a handful of people remained.

But the story of Brunswick Town doesnt end there. In the coming century Brunswick Town would once more find itself in the midst of war and rebellion as it started a new life as part of the Confederacys defensive network guarding the Cape Fear River and key port of Wilmington. And after that it would become a player in one of the darkest hours of 19th century America.

Dont miss The Forgotten Tale of Brunswick Town Part II in the March issue!