Coastal Coaches

Stagecoaches in Southeastern North Carolina

BY David A. Norris

To anyone who’s watched TV or movie Westerns, the stagecoach is an enduring symbol of the Old West.

Besides playing a top role in the history of the American West, the stagecoach also played a part in the history of Wilmington, Fayetteville, and indeed all of North Carolina.

Stagecoaches first flourished in England in the years after the restoration of King Charles II in 1661. Companies established depots, perhaps 10 or 15 miles apart, where each “stage” of a journey was briefly halted for a change of horses. With fresh horses, stagecoaches could run all day and into the night, revolutionizing land travel in Great Britain and Europe.

In America, a land of towns scattered through sparsely populated farmlands and forests, stage travel developed in the late 1700s. In North Carolina, a stage line started running between Edenton and Suffolk, Virginia, in 1789.

The United States Post Office began regular mail service connecting Portland, Maine, with Savannah, Georgia, in 1789. Part of the route followed the Colonial-era King’s Road, which foreshadowed the path of modern U.S. 17, from New Bern to Wilmington.

Until February 1803, mail was carried by a horseback rider for the 408 miles between Petersburg, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina.

By the time the first mail coaches reached Wilmington, a separate Wilmington-Fayetteville stage line had already started in January 1800. The company made one round trip a week. The stage departed from Dorsey’s Hotel (on the eastern side of Front Street between Market and Princess, where the Art Deco façade of the old Bailey Theatre stands now) at 7 a.m. on Sunday. A stagecoach company ad in the Wilmington Gazette on Jan. 16, 1800, advertised going “by way of Point Peter and Black River.” The stage arrived in Fayetteville on Monday afternoon.

Passengers in Fayetteville boarded the stage at the “public house” of Michael Molton at 7 a.m. Wednesday and arrived in Wilmington the next day. Passengers paid $6 each way.

The Wilmington and Fayetteville stage company lacked a federal mail contract and was forbidden to carry letters.

Peter Mallett, a Fayetteville merchant, was apparently the main owner of the Wilmington and Fayetteville Stage Company. After Mallett’s death in 1804, his executors advertised that the stage company was for sale, including “two Stages, one quite new, nine Horses, with the Corn at the stands on the road, etc.”

Nowadays, the trip between Wilmington and Fayetteville is about 90 miles by road and takes a bit over one and a half hours. In the early 1800s, it might have taken a traveler on horseback three days or more.

Before steamboats, river travel between Wilmington and Fayetteville was slow and difficult. Low water could leave boats stranded for days. A day and a half by stagecoach was an option.

Stage travel was neither luxurious nor comfortable. Coaches of the early 1800s were rather egg-shaped, and usually had three benches for passengers. The middle and front benches had no backs, so passengers perched awkwardly on them for hours. People were often thrown out of their seats, or into each other, when the coach lurched into holes and ruts in the roads. Later coaches had flat roofs, so additional passengers could ride on top.

If a stage got stuck in a mud hole, passengers had to at least get out, and might have to help push the stage back into service.

Capt. Basil Hall, a British naval officer, toured the United States in 1827-28. In eastern North Carolina, Hall rode in a stagecoach he described as a “lumbering, creaking vehicle” in the Sept. 17, 1829, edition of the Fayetteville Observer. On the rough roads, he said “we came every now and then to pools a quarter of a mile in length, through which the horses splashed and floundered … drawing the carriage after them in spite of the holes, into which the fore-wheels were dipped almost to the axle-trees, making every part of the vehicle creak again.”

Hall’s book Travels in North America, in the Years 1827 and 1828 was published in 1829.

Rather than install expensive and fragile glass, stage companies left the windows unglazed and utilized leather curtains to protect passengers from rain and cold winds. Sometimes, straw was dumped on the floor to provide a little insulation.

The weather turned frosty during Hall’s trip through North Carolina in February. The cold air “stole into the carriage through the openings between the curtains, or by sundry cracks we had either not seen nor cared about before …”

Trying to keep warm, he reported passengers “in vain wrapped ourselves in cloaks, and stamped our feet …”

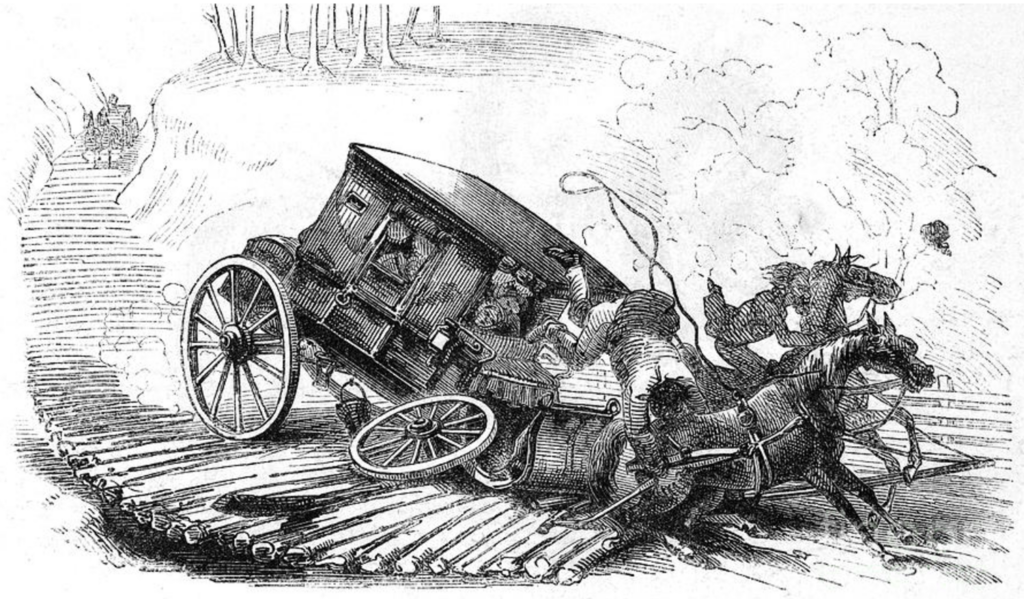

Frightened horses, flooded roads and other perils added danger to the discomforts of stage travel. A driver was killed two miles from Wilmington in 1837. His lead horses were reported by The Weekly Standard (Raleigh) on Aug. 23, 1837, as having “took fright” and “the driver sprang from his box in order to seize them, when his foot slipping, he fell and the stage passed over him; he was taken to Wilmington and expired in a few hours. The driver’s name was Benjamin Griffith, of Sweet Springs, Virginia; he is represented to have been a fine young man.”

In 1826, the stage running from Louisburg to Warrenton usually crossed a ford on the route at Shocco Creek. Finding the ford was deep under swirling flood waters, the driver detoured to cross the creek by a bridge some distance away.

The North Carolina Star (Raleigh) told the story on Oct. 27, 1826: “As soon as the stage got on the bridge, it floated off with the stage, passengers, horses, and all, but by the great exertions of the driver, they were all saved. He swam to shore, and having obtained help, returned and carried the passengers one at a time to land on his back.”

War brought new perils to stage travelers. In early July 1863, a force of Union cavalry left New Bern for a raid on the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad. On July 5, 1863, the cavalry reached the tracks at Warsaw.

The raiders burned the railroad station and some army supplies, and captured the Warsaw-Fayetteville stagecoach. The horses and the mail were seized and taken to New Bern, but the passengers escaped.

In 1800, passengers on the Wilmington-Fayetteville Stage were entitled to bring 14 pounds of baggage, but it cost $1 for each 20 pounds over that.

Early stagecoaches had little if any space for storing luggage. Passengers had to hold their baggage or shove it under the seats. When stage companies began taking more luggage, bags and trunks were secured to the outside of the coach with leather straps. Stagecoach robbers in North Carolina and elsewhere were usually petty thieves who cut the luggage straps and ran off with bags or parcels.

In 1830s Wilmington, the Clarendon Hotel served as the post office and a stagecoach stop. The Clarendon stood on Front Street, in the same spot as the old Dorsey’s Hotel. Front Street was not graded and leveled as it is now.

In 1878, “The stage road near Red Cross street, just where the railroad tracks now are, crossed quite a stream of water some two to five feet deep,” (the Wilmington Sun, April 15, 1879).

From there the stage would head to the ferry at Point Peter. Stages traveling south took the ferry at the foot of Market Street to cross the river. Stages heading east left along Market Street to the old New Bern Road.

Stage drivers traditionally blew a trumpet to mark their arrival. Children idolized the stage drivers, who seemed to have lives far more exciting and adventurous than their own. Many workers found an excuse to leave their desks or counters for a few minutes to watch the stage.

A stage line opened between Smithville (modern-day Southport) and Georgetown, South Carolina, in 1831. Mail and passengers leaving Wilmington traveled by boat down the Cape Fear to Smithville to board the stage.

Wilmington-Fayetteville stages ran until at least 1837. By then, steamboats plied the Cape Fear River. Sandbars and snags were being removed, making river travel smoother and more reliable. Railroads were also beginning to be built in North Carolina.

Steamboats and railroads did not immediately replace horse-drawn intercity travel. For some time, stage lines did profitable business taking passengers from small towns and the countryside to port cities such as Wilmington and New Bern, as well as railroad towns such as Warsaw and Goldsboro.

In 1836, work began on the famous Wilmington & Weldon Railroad. Crews worked from both ends at the same time. Stagecoaches carried passengers across the gap between the two sections of track until construction was finished in 1840. In 1841, the railroad sold its 14 stagecoaches at auction in Wilmington.

The Wilmington & Manchester Railroad once took passengers from Eagle Island across from Wilmington into South Carolina, where they could get connections to Charleston and Savannah. When that railroad was under construction in the early 1850s, it also used a fleet of stagecoaches to carry passengers across the unfinished section.

In eastern North Carolina from the late 1830s into the 1870s, new stagecoach lines linked railroads to towns beyond their tracks. In 1859, Fayetteville was not linked by rail with Wilmington or Raleigh. But Fayetteville had a daily stage service running to Raleigh and to the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad at Warsaw.

A tri-weekly stagecoach ran between Fayetteville and High Point. Holmes & Robinson’s Three Horse Stage Line connected Fayetteville to Warsaw and Kenansville in 1859. A year later, the service was replaced by Beaman & Robinson’s Four Horse Stage Line. “Our Coaches are large and comfortable, drivers sober and gentlemanly, our teams good and sure of five miles an hour,” promised their ad in the Fayetteville Observer. Leaving Fayetteville at 2 p.m., the coach took 10 hours to finish the journey at Kenansville.

Cape Fear River steamboats concentrated on freight rather than comfortable passenger cabins. So some Wilmingtonians traveling to Fayetteville preferred taking the train to Warsaw, and riding the stage the rest of the way.

Passengers could buy combined stagecoach-railroad tickets. In 1870, the trip from Wilmington to Warsaw by the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad and from Warsaw to Fayetteville via Clemmons’ Stage Lines cost $6.

Stage service between Fayetteville and Warsaw ran as late as 1877. Soon, lines operating in eastern and central North Carolina went out of business.

In the North Carolina mountains, stagecoaches lasted into the early 1900s, their business fueled by passengers heading from railroad stations to hotels and resorts.

Today, some roads once plied by stagecoaches are modern highways, covered in pavement instead of mud or dust. Parts of N.C. 87 are also known as the Old Stage Road, commemorating the days when it was part of the route between Fayetteville and the Cape Fear River ferry landing across from Wilmington.