Chasing Redfish On Lea Island

In a deep slough just under the shoal edge, the school of reds lay in perfect casting range

BY Robert Rehder

Our friend Sammy Corbett, long-time Pender County waterman and commercial crabber, told us, “Go to Lea Island across from Dead Man’s Bay. There’s a creek there that flows out to the ocean on falling tide. I’ve seen a big school of redfish lying off the surf in front of the island. They’re probably feeding on fiddler crabs from the creek. They’ve been there for the past week just where the creek outfalls to the ocean.”

That conversation brought Hampstead outdoorsman and light tackle expert Allen Warwick and me to Lea Island the next day on a beautiful, cool September afternoon, threading our boats through the oyster rocks, bars, and backwater maze to our campsite, hoping to find that school of redfish. It was late afternoon when we moored our boats in a deep, calm lagoon and camped high among the massive backbone of dunes in the maritime forest above Dead Man’s Bay.

It was a glorious place to camp. The surf boomed and crashed before us, and the clear, salt creek swirled and eddied below us. There was a hint of autumn in the air with a fresh west wind whistling through the marshes.

Red bay, cherry laurel, and live oaks surrounded our campsite and boughs of cedar gave off a pungent, aromatic scent. Petite scarlet flowers known as Indian blanket grew along the lower slopes with pink horsemint and delicate white blooms of wild blackberries. Driftwood for our fire was plentiful, and the rough camp was warm and comfortable.

Wildlife on the island was always stunning with its lovely, natural harmonies. In the evenings, doves sailed in from mainland fields to roost in the protective oaks. A scarlet king snake hunted along the wildflower beds. Marsh rabbits scurried through the thick blackberry hedges, and the deep resonant call of a barred owl echoed from down the ridge.

Marsh hens called from their perches in the hammocks, and high overhead an osprey folded her wings and dove like lightning to impale a small flounder from a shallow pond. Striking orange and black monarch butterflies fluttered among the dunes and swamp milkweed plants. Sunset came early, and the marsh lay still and calm. Along the horizon, rose-fringed clouds billowed high in the western sky, catching the last rays of sunset. As night came, red, blue, and gold hues from the campfire’s embers danced among the deepening shadows, and the island slept to the ocean’s peaceful rhythm.

The first night started bright and clear with endless stars and spectacular meteors trailing and falling across the sky. But barrier island weather is always fickle and by morning the wind switched hard to the northeast and a sudden squall, so typical of the coast, rustled our tents, rumbled through the dunes, and smoked along the beaches. The surf was a churning, gusty blast that flung walls of spray cascading high into the air above the breaking waves.

Too rough to fish in the fierce, inshore wind, we stuck close to camp, exploring the stormy beaches, looking for new rips and sloughs. With our cast nets, we netted fat mullets in the backwater oxbows and baby shrimp from the creeks. We raked a bucket of cherrystone clams from the flats. Supper was smoked mullet over oak coals with wild rosemary from the forest, boiled shrimp, fried clam strips and strong coffee.

The wind calmed during the night and turned west. The next morning, the sky was steel-blue, cool and fresh after the northeaster. I woke to a glassy, emerald sea ripped with new eddies, shoals, and sloughs fashioned by the storm. A smoky red sun rose from the depths of the sea as I climbed to the dune tops with my binoculars, scanning the surf for the telltale, dark mass that spelled a school of reds in the surf.

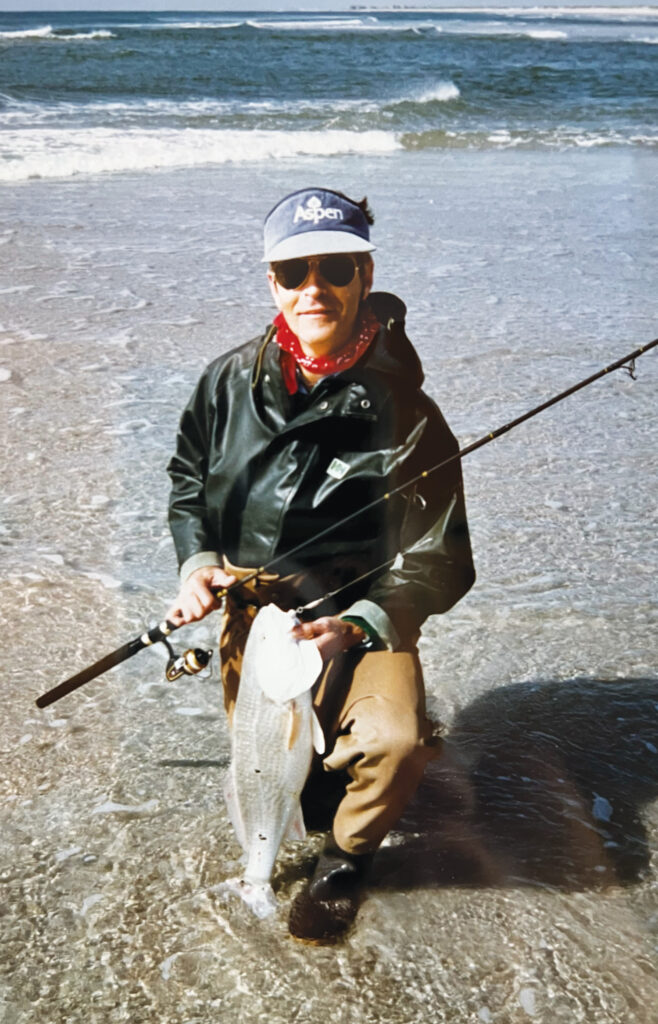

Allen had a remarkably consistent, almost mysterious ability to find fish and game. He kept in top physical shape and whether we were fishing on the islands or hunting wild turkeys or upland birds, it was routine for him to be a mile from camp before breakfast, patiently scouting, observing and listening.

That morning, I thought Allen was still in his tent sleeping, and while the coffee was brewing, I was glassing the beach fronts north and south hoping I could spot the school. What I saw was lots of beautiful water with nothing in it.

Then in the distance up the north beach I made out a human form in the early mist, jogging at a fast clip back toward the campsite. After 40 years of observing his uncanny ability, I should have known who it was. The school was moving, displaced by the storm, and Allen was already out and had found the fish feeding in a deep slough just off the beach almost a mile north of the creek that Sammy mentioned.

We grabbed our packs and gear and scrambled down to the surf for a long jog back up the north beach. When we got there, I saw what a surf fisherman dreams of. A swirling rip had driven a wall of water cascading against the barrier shoal just offshore. In a deep slough just under the shoal edge, the school of reds lay in perfect casting range, stacked like cordwood in the clear waves, flashing silver in the morning light.

They had hemmed a school of finger mullets against the shoal, and the mullets were trapped with no escape. Just as we waded into the slough, a moving explosion ripped through the surface as the reds cut into the baitfish just where the deep water hit the curl of the slough.

In a mass of slashing, churning confusion, the surface was alive with big spotted tails, curling wakes, screaming birds, and squirming minnows. Chased into the air, the baitfish showered through the surface in gleaming, watery arcs as the predators attacked. Above us, the gulls circled, screamed, banked, dove for scraps, and then fought each other for the remains.

We cast into the swirling rip, and immediately our rods plunged and pulsed with the light Shimano reels singing. We had one-piece, graphite rods with 10-pound braid, 15-pound fluorocarbon leaders and twitch baits.

A fish would strike the lure just as it hit the water with multiple fish trailing. We caught fish ranging from 20 to 30 inches — 6 to 15 pounds — with every cast and then carefully released each. These were heavy, hungry fish on a wild feeding spree famous for their intense fight, and for over an hour our drags whined with every strike.

Then nature’s silent clock suddenly tolled, the tide changed, and in minutes the fierce rip tide melted back into the sea, and the furious action stopped just like it never happened. The fish moved off, the gulls and terns flew back to their sandbars to watch and wait for the next battle, and the slough was again flat, still, and quiet.

Waist-high in the slough, we stood there in silence — happy, exhausted, treasuring the island, the fish, and the wildness that surrounded us. It was all quite perfect and much more than we had hoped for.

Calm and silent once again, the eddy swirled and rolled before us in a blue-green wash. Pinfish and little blue crabs scurried around our feet, scavenging the shreds of battle. We left camp that day, never again to share such an incredible adventure.

Authors note: Allen Warwick was my companion and guide on this trip. It would be our last outing together. Soon after, Allen was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and the affliction rapidly progressed. He took a fall at his home in April 2024 with resulting complications, and he never recovered.