An Endangered Culture

BY Simon Gonzalez

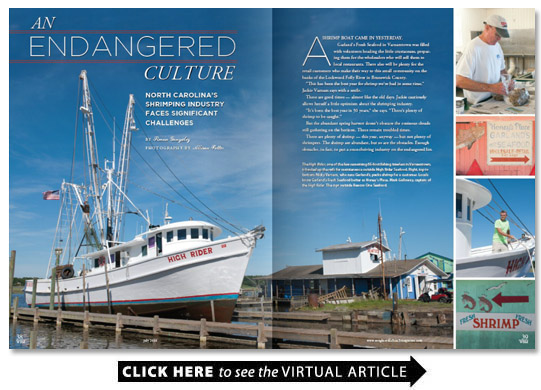

Garland’s Fresh Seafood in Varnamtown was filled with volunteers heading the little crustaceans preparing them for the wholesalers who will sell them to local restaurants. There also will be plenty for the retail customers who make their way to this small community on the banks of the Lockwood Folly River in Brunswick County.

“This has been the best year for shrimp we’ve had in some time ” Jackie Varnam says with a smile.

These are good times — almost like the old days. Jackie cautiously allows herself a little optimism about the shrimping industry.

“It’s been the best year in 50 years ” she says. “There’s plenty of shrimp to be caught.”

But the abundant spring harvest doesn’t obscure the ominous clouds still gathering on the horizon. These remain troubled times.

There are plenty of shrimp — this year anyway — but not plenty of shrimpers. The shrimp are abundant but so are the obstacles. Enough obstacles in fact to put a once-thriving industry on the endangered list.

Even while talking about how good it is this year Jackie concedes that these are difficult days.

“Well you would say that if you see the number of boats ” she says. “There’s only a few that are local where there used to be 30-something.”

In the past virtually everyone around here made their living off the water’s bounty. Now people like Jackie and her husband Nicky face an uncertain future.

“There’ll always be shrimp ” Nicky Varnam says. “But there ain’t going to be no shrimpers left.”

It’s happening all over the state.

“Studies showed our licensed fishermen were getting older ” says Patricia Smith public information officer with the Division of Marine Fisheries in Morehead City. “In a nutshell if you are looking at the long-term over the past 20 years you’ve seen commercial fishing drop statewide in the number of towns where commercial fishing is harvested and the number of people in the business.”

Bimbo Melton one member of a large fishing family that lived in a home where Boca Bay restaurant now stands once worked alongside more than a dozen shrimpers out of Wrightsville Beach. Today his 28-foot boat is one of the few remaining docked on Motts Creek. He explains that young boys now don’t pursue shrimping as a career.

“People are getting out of it because there’s no money in it ” he says.

Wrightsville resident Sheila McCuston agrees that not many shrimpers remain on the island today although some faithfuls like her husband Denny are still shrimping.

“Denny just renewed his license yesterday ” she said in early June.

It once was so simple: trawl net and haul the shrimp; sell the shrimp; make a decent living. These days shrimpers and other commercial fishermen say they are besieged by regulations prohibitive costs developers buying up all the waterfront property and unfair competition from cheap imported seafood.

”It’s a great profession but there are a lot of barriers to entry ” says Mark Blevins the county extension director for Brunswick County and a board member of NC Catch a group dedicated to promoting the state’s seafood economy. “Not a lot of young people are getting into it because of the barriers — regulations cost. It’s tougher and tougher to make a living.”

Few places are feeling the pinch as keenly as small coastal towns like Varnamtown where just about everyone once depended on fishing.

The town sits on the west bank of the Lockwood Folly River home to a few hundred folks. It wasn’t officially named until 1988 when it was incorporated. But it has been called Varnamtown for as long as anyone can remember.

The Varnams first settled the area before the Civil War when Roland Varnam moved here from Bowdoinham Maine. “The Carolina Watermen: Bug Hunters and Boat Builders” says Roland married an American Indian girl named Sarah Jane Pridgen and had six sons.

One son John was born on April 2 1869 in Smithville Township. He apprenticed with a boat builder Mr. Manuel in Southport when he was 10. John came back home after his mentor died and began to build shrimp boats.

The Varnams have been involved with the water and shrimping ever since either building boats trawling or selling the catch.

Nicky Varnam is carrying on the family tradition.

“I was born and raised on the river ” he says. “I shrimped with my daddy since I was 12 years old. Outboard motor shrimping in the creeks. I went from there to larger-sized boats. I shrimped 18 years.”

A couple of years before he started shrimping his father built a fish house down by the boat ramp. Mere weeks after Garland Varnam opened it Hurricane Hazel hit. The fierce storm that devastated the North Carolina coast in 1954 knocked it down. Undeterred Garland rebuilt in a new location.

“Hazel came along and moved it up the river ” Nicky says. “We took some of the old lumber and built it back up. Brunswick Electric told him he could have all them old light poles all along the beach. Me him and my brother would take the skiff — an old rowboat we didn’t have no outboard motor back then — put about 10 light poles on a piece of rope and row them across. He caught the tide coming up and floated them in here.”

It happened nearly 62 years ago but Nicky vividly remembers cutting the lumber the old-fashioned way with a big crosscut saw.

“We didn’t have any skill saws ” he says. “It was one on one end and one on the other. One would push and the other pull. And a drill was an old bit you would crank by hand.”

Garland’s Fresh Seafood has stood ever since ready to accept shrimp blue crabs grouper flounder — the catch of the day whatever’s in season.

“We’ve been in business for 61 years ” Jackie says. “We’re the oldest business in the county.”

Even though it has been around for six decades locals might give you a blank look if you ask for Garland’s Fresh Seafood. They know it better as Honey’s Place.

“Nicky’s daddy called everybody ‘honey ‘ male or female ” Jackie says. “If you were a close friend he called you ‘bee.’ That’s how Honey’s Place came to get its name.”

While Garland was running the fish house Nicky was out shrimping. After starting on the skiff with an outboard motor he soon moved to bigger boats. He had three trawlers over the years. Like other shrimpers he’d stay out for up to a week at a time in the spring when shrimp are found in the shallow estuaries. When the weather warmed and the growing shrimp moved into the cooler deeper water of Pamlico Sound he’d joined the Brunswick County shrimpers following their migration north.

It wasn’t an easy life. The work was hard; the weather catch and income uncertain.

“Shrimp run in cycles ” Melton explains. “You can’t predict it. Storms might affect it. Everything weather-related will affect it. Water temperatures might kill them.”

Despite the uncertainties Nicky loved it.

“Shrimping is addictive ” he says. “Very addictive. It’s enjoyable dumping the nets and watching those shrimp pour out.”

He came in off the water when Garland couldn’t run the fish house anymore.

“I came in here in 1984 to help my wife run it ” he says. “My daddy got sick. I stepped in his shoes and I thought I stepped on an ants’ nest. I didn’t know there was so much work to be done. When you’re shrimpin’ it’s a whole lot different than running a business.”

He took over the family business but there was no family to take over his boat. Nicky might be the last Varnam to shrimp.

“Our problem was we had three girls ” Jackie Varnam says with a laugh.

Even if they had boys it’s far from certain that they would become shrimpers. Used to be sons followed fathers into the business. Now they don’t.

Melton who will turn 60 this year says his son is not interested in taking up the family business of shrimping and every day the desire to persuade him lessens.

“I’ve been doing it all my life ” he explains. “I was born and raised in it. My granddaddy had a fish and produce stand right there behind Babies Hospital. I have a son but he’s not interested. I’ve tried to get him interested but now I don’t really want him in it. It’s getting harder and harder to make a living at it.”

Durham-based artist Tony Alderman has made several trips to Brunswick County to paint in Varnamtown and to raise awareness for the plight of the shrimpers and commercial fishermen. He calls his series of paintings “An Aging Life.”

No one disagrees with the title.

”Everybody’s getting out of it ” Nicky Varnam says. “The young generation is not getting into it.”

The words come out matter-of-fact almost with a shrug. What will be will be. A lifetime of shrimping and fishing teaches you that there are many things you can’t control.

A few years ago a filmmaker came to Varnamtown and put together a mini documentary. Jackie Varnam has watched it many times before. She pulls it up on her smartphone and listens to the introduction.

“The locals here are nervous ” the narrator says. “Actually they’re downright scared. They fear that they are literally watching the death of their fishing culture.”

Jackie laughs in a “you can’t trust the media” way. The intro is maybe a little overly dramatic. Nervous? Maybe. Downright scared? Definitely not.

“I guess I’m mellow ” she says. “I’m ready to retire.”

Concerned? Of course.

“We used to have eight boats here ” Nicky says. “It’s down to two small ones now. We’re all aging out. They’re not building no more boats. There used to be seven boatyards here. Now they don’t have any. That’s where Roland Varnam and all them got started building boats.”

Jackie doesn’t watch the video for the doom-and-gloom opening. There’s a quote from an old shrimper named Danny Galloway that she likes because it sums up this way of life.

“If you live to shrimp you might make it ” Galloway says. “If you shrimp to live you’ll go busted. That’s about what it amounts to.”

Live to shrimp. That’s what keeps men like Arthur Thompson going.

“I’m an old-timer ” he says. “I was a shrimper for 55 years. Started in 1945. Family business.”

Thompson retired for a spell but sitting around idle wasn’t for him.

“It’s boring ” he says. “You’ve got to have something to do.”

He’s 83 and just bought a small shrimp boat. He named it Old Man. Getting back into shrimping earns him some good-natured ribbing.

“What day did he have a brain freeze?” Jackie laughs.

Before putting a winch on the boat Thompson tries to explain why he’s getting back into this difficult business in these uncertain times.

“I don’t know what it is ” he says. “It’s hard work. But hard work ain’t gonna kill you. If it did I’d have been dead a long time ago. I don’t worry about it. Either I make it or I don’t.”

Stoicism seems to be typical of shrimpers. Either they make it or they don’t. Either there will be shrimp or there won’t.

But that doesn’t mean they are ready to see it all end. It might be an aging life but they are not ready for it to be a dying life.

Jackie is president of Brunswick Catch one of four groups within NC Catch.

“A group of locals shrimpers restaurant owners seafood dealers — we all got together to see how we could promote the industry and enlighten our customers about wild-caught seafood ” she says. “About 86 percent of all seafood is imported from Asia and South America farm raised. People here on the coast have an advantage to getting the local seafood. When you go into a business ask for wild-caught the local stuff. Just ask for local.”

Mark Blevins agrees that buying local is a great way to support the industry.

“The seafood is delicious ” he says. “We have an incredible diversity of seafood species here on the North Carolina coast. Go to a local fish house. Go and listen. Talk to some folks. The stories are incredible. And they will have recipes for you.”

Blevins has developed a deep affection of and appreciation for the shrimpers and other fisherman since he arrived in Brunswick County about five years ago.

“These are hard-working folks that love being on the water and love our coastal resources and want to protect them ” he says. “It’s not an easy industry. It never has been. It’s not growing that’s for certain. But it’s not dead and it’d better not get dead. There’s a lot of people working really hard to make sure our North Carolina seafood industry remains a viable part of our coastal industry.”

Still there’s a lot of uncertainty that can make it hard to be optimistic about the future. Nicky is 70. Jackie doesn’t give her age but says the couple has been married for 48 years and she was over 18 when they got hitched. They’d rather not work into their 80s. But who will take over the business?

“I’ve got three grandsons ” Jackie says. “I’m not going to pick and choose.”

In the meantime all she can do is hope that there will always be boats headed out the Lockwood Folly and back in again with a bountiful catch ready to be dumped at Honey’s Place.

“I hope it stays competitive and there’s plenty of shrimp to be caught ” she says.