A Little Creek with a Big Story

The meandering history of Howe Creek

BY David A. Norris

Part of the fun of visiting Mayfaire Town Center is adding a walk along the sidewalks that wind around the retention ponds behind the shopping center. Another sidewalk goes by a little creek on the north side, cutting its way through a quiet patch of woods just a stone’s throw from the busy shops and parking lots.

The creek flowing by Mayfaire is Howe Creek. Within just 2.5 miles or so (as the crow flies) the little creek makes its way into open wetlands, widens, and flows by the northern edge of Landfall into the Intracoastal Waterway at Middle Sound.

Not only water passes through Howe Creek. There’s a great deal of history flowing through the stream, past its neighboring lands, and into the salt waters of the sound.

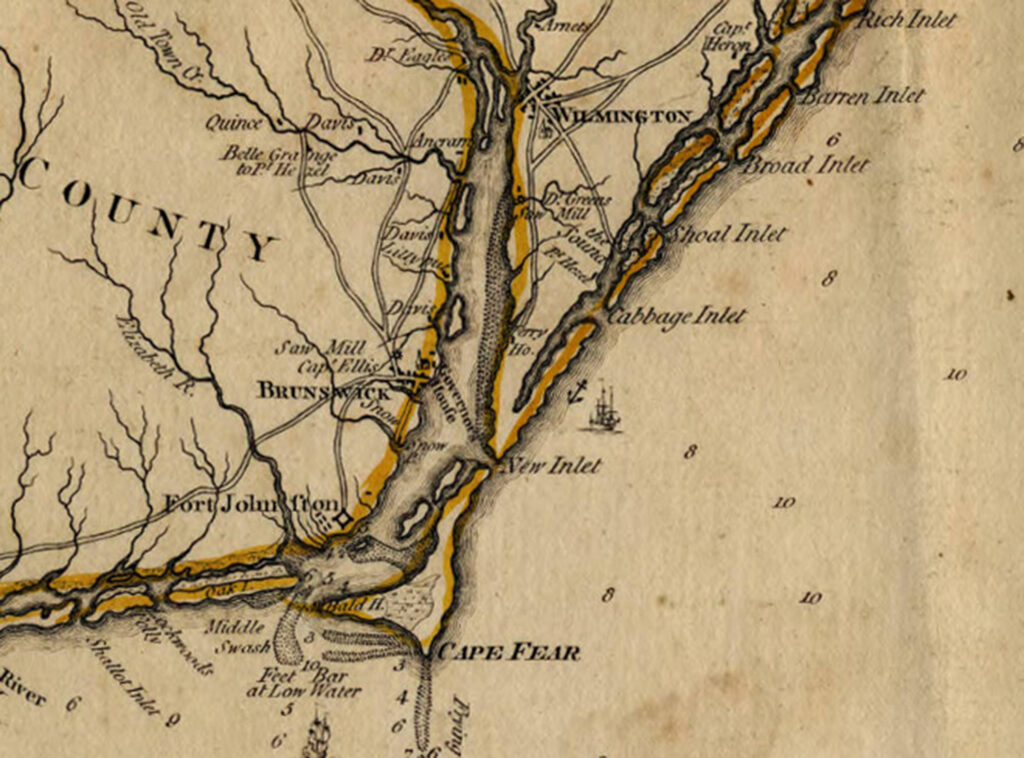

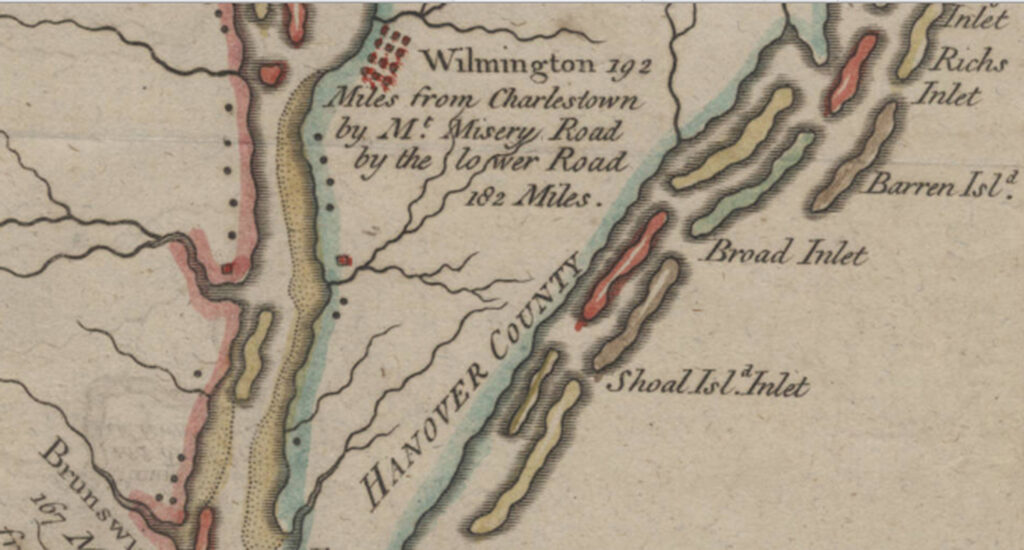

The mouth of Howe Creek lies opposite Mason Inlet, the waterway dividing northern Wrightsville Beach from Figure Eight Island. Inlets along barrier islands have a way of coming and going. The Mosely Map of 1733 shows an inlet called Barren Inlet occupying much the same space as present day Mason Inlet.

John Brickell’s Natural History of North Carolina, published in Dublin, Ireland, in 1737, also mentions Barren Inlet. The nearby creek got the name Barren Inlet Creek, or just Barren Creek. William S. Powell’s North Carolina Gazetteer mentions that the name Barren Inlet appeared on a map as late as 1909. The passage was next called Queen’s Inlet from 1909-1936.

Job Howe was one of the first known landowners to live by Barren Inlet Creek. He obtained two large land grants from the British crown near the creek “between the sound and the main road” in 1761. Howe died in 1775, leaving land north of the creek to his sons Job and Thomas, and land south of Barren Inlet Creek to his son Robert.

In 1805, the executor of Robert Howe’s estate advertised the sale of 640 acres at Barren Inlet Creek. It seems that Howe Creek and Howe Point got their names from this family.

Margaret Howe, daughter of the younger Job Howe, died in 1846. She left her land along the sound and the north side of Barren Inlet Creek to her nephew, Frederick A. Moore.

Farther upstream, Thomas F. Davis won permission from the New Hanover County Court in 1813 to build a grist mill at the head of Barren Inlet Creek. It would not have been a bad choice for a mill site. The upper part of the creek ran near the old New Bern Road. Now the route of Market Street and U.S. 17, it once was part of the colonial post road that passed through Wilmington on its route from Savannah, Georgia, to New England.

Historical creek and stream names can be confusing. The name of Barren Inlet Creek remained in use off and on until at least the late 1900s. But an 1863 map labels Howe Creek as Moore’s Creek, evidently after the Moore family who lived by its banks.

An 1869 map shows another Moore’s Creek, flowing into the sound between what is now Bradley Creek and modern Howe Creek.

A 1921 newspaper article about a proposed coastal road mentioned that this Moore’s Creek was two miles from Summer Rest near Wrightsville Beach, and so about another mile or so south of Howe Creek. (Neither of these Moore’s Creeks should be confused with the Moores Creek in Pender County, made famous by the 1776 Battle of Moores Creek Bridge.)

Barren Inlet

In the late 1870s, the Wilmington press reported some local legends about Barren Inlet and the nearby area of the mainland. By this time, former New Hanover County Sheriff A. R. Black lived on the property once owned by Margaret Howe and Frederick A. Moore.

While he lived there, Moore had taken a great interest in a plentiful supply of old bones that were uncovered by plowing the farm fields. Once, the skeletons of a horse and a man were found buried together.

Black showed several reporters and amateur historians around the property, generating newspaper articles that spun fanciful stories about the secrets held on the land.

Tradition had it that Barren Inlet once was deep enough to allow in ships the size of the one sailed by infamous pirate Edward Teach, known as Blackbeard. Some local folks had the grim thought “that these deposits of bones are the remains of [Blackbeard’s] victims, captured at sea.”

The reporter also saw “the remains of an old live oak (a dead live oak!) … under which it is said that Blackbeard used to rest when his vessel was in the Sound.”

Capt. Jack Hewlett, who in the 1880s was known as the patriarch of Masonboro Sound, related more pirate lore about Barren Inlet. Hewlett claimed that the Hammocks (the sandy island that now forms much of Harbor Island) was once called Barren’s Island. Tales had long been told that famed pirate Captain Kidd buried his treasure near Wrightsville Beach on Money Island. Hewlett recalled that Money Island was once called Mooney’s Island. And, he also had heard that Captain Kidd sailed through Barren Inlet (not nearby Masonboro Inlet) when he found a spot to bury his treasure in 1699.

No one was able to explain the mystery of the skeletons of the human being and the horse being buried together. But when antiquarians with knowledge of regional archaeology examined bones plowed up around Howe Creek, it was apparent that instead of being the remains of Blackbeard’s victims, they came from Native American burials.

Barren Inlet was never busy, but the passage saw occasional use from seagoing vessels. The schooner Two Sisters of New River in Onslow County was driven onto the beach near Barren Inlet by an 1806 hurricane.

A hurricane in 1848 stranded the schooner Caldwell, bound from Mattamuskeet to Wilmington, in Barren Inlet. Captain Hoover of the Caldwell had hailed a brig and asked for help, but the “captain of the brig said it was as much as he could to save himself, and told him to luff the schr., he doing so, the brig luffing at the same time came very near running into the schr.,” reported the South Carolina Charleston Courier, August 23, 1848. (Schr. was the abbreviation for a schooner.)

The Caldwell was a total loss, but the crew was saved, and some sails and rigging were salvaged.

One schooner managed to get through Barren Inlet in 1880. Loaded with lumber, the Lillian was bound from Wilmington to Wrightsville Beach, at the beginning of a decade when residential and vacation construction was growing by the ocean and the sound. The area was not linked to Wilmington until the Wilmington Sea Coast Railroad opened in 1888, so dropping off lumber by schooner was a tempting option. The Lillian tried to sail through Masonboro Inlet but ran aground. After dumping part of her deck cargo, the Lillian slipped through Barren Inlet, which was then 3 miles north of Masonboro Inlet.

The fall of 1881 brought a hurricane to the New Hanover County coast. Ships were damaged or lost.

“The coast for miles in the neighborhood of the Cape Fear is lined with lumber from wrecks which went down in the recent storm,” according to the Wilmington Morning Star on Sept. 17, 1881.

Heavy timber from the cargo of La Louisiana, a Norwegian vessel shipwrecked on Frying Pan Shoals, washed up all around Masonboro Inlet. “Narrow lumber” from unnamed wrecks floated into Middle Sound and washed up around A. R. Black’s place near Howe Creek. Fittingly, in 1885, Black was named a commissioner of wrecks by the governor.

In December 1882, the schooner Ray left Swansboro for Wilmington. The captain tried to put into Barren Inlet for the night, but the ship “struck on a bar, sprung a leak, filled with water, and the captain and crew had to leave her and reach the shore as best they could,” said the Morning Star. Much of the cargo of cotton and turpentine floated off. “Men were sent down to try and save as much of the cargo as possible and also to endeavor to float the schooner off.”

By March 1883, the Ray was repaired and back at sea running between Wilmington and Swansboro. “She looks as bright as a new pin now,” said the Morning Star.

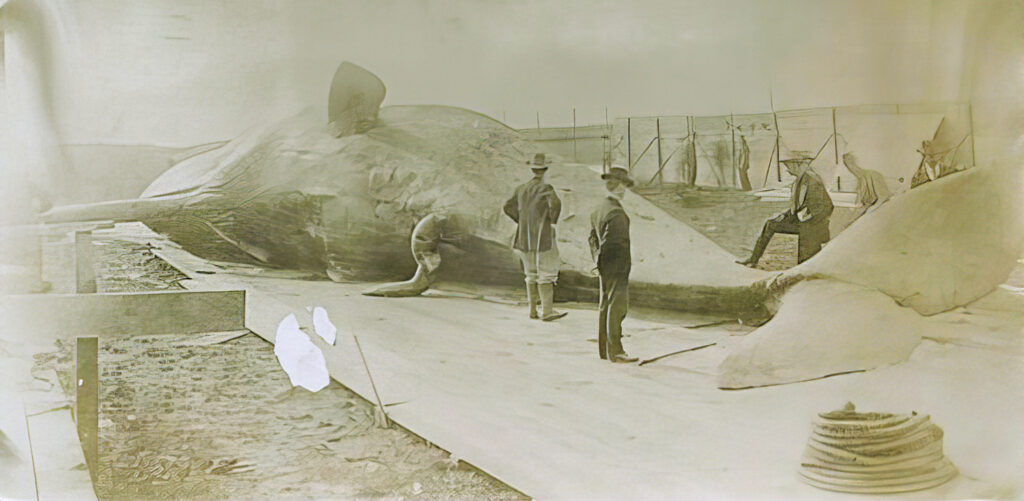

Lumber wasn’t all that washed up in the area. Not far south of Howe Creek, on land owned by the Moore family (now part of Landfall), a 51-foot-long sperm whale washed ashore in Middle Sound in 1889.

“It is being cut up now and the oil tried out by those who discovered it,” said the Daily Review.

To the South

Pembroke Jones, who lived at Airlie House with his wife, Sadie, began expanding his land holdings beyond today’s Airlie Gardens after the turn of the 20th century.

In 1902, Jones bought three tracts totaling almost 1,300 acres for $3,300. The land ran along Wrightsville Sound and Middle Sound and stretched from the (now) Airlie Gardens area north to some of the old Howe acreage on the southern banks of Barren Inlet Creek. It would have included the place where the whale washed up in 1889.

Jones’s new tract came to be called Pembroke Park.

Former Sheriff A. R. Black’s land, known as the Black Place, was described in 1919 real estate ads. “Faces Middle Sound and Barren Inlet Creek … beautifully located and adjoins Pembroke Park on the north … contains four hundred and twenty-one (421) acres besides beach and marshland.”

Jones used Pembroke Park land as a hunting preserve and built a lodge, which more resembled a mansion, where he entertained guests at parties and gatherings.

South of the banks of Barren Inlet Creek or Howe Creek, some land was converted to pasture or corn and oat fields for Jones’s saddle horses. It was the only portion of Pembroke Park that was cultivated for farming or used as pasture. The lodge stood empty for years and was damaged by vandalism and arson until it had to be demolished. Jones’s hunting preserve was later developed into the community of Landfall.

Howe Creek, steeped in many years of history and legend, still flows quietly past the northern edges of Landfall on its way to the sea.