A Layman’s (Unofficial) History of Carolina Beach

A look at some of the important people, dates and events that comprise its history

BY Pat Bradford

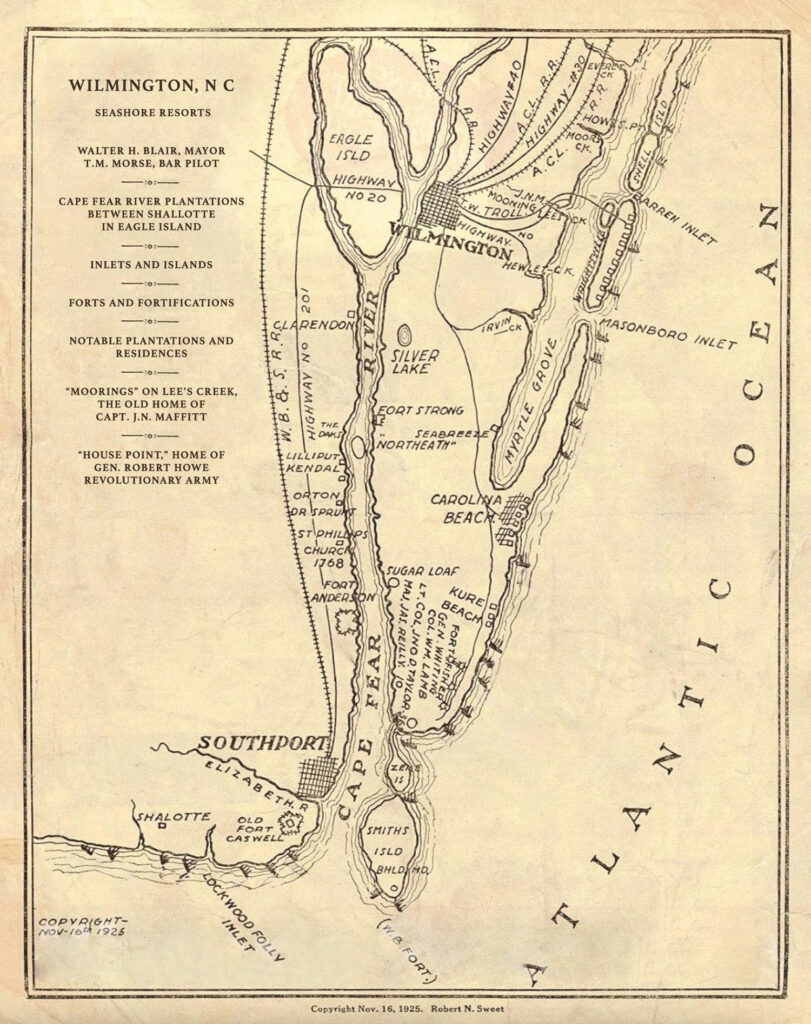

In the greater Wilmington metro area, Carolina Beach, with a population of 6,500 in the 2020 census, has its own special history dating back to before English settlers arrived in the 1700s.

The first inhabitants were Native Americans.

The Cape Fear Indians, associated with North Carolina’s eastern Siouan tribes, made a settlement on the east bank of the Sapona River at Sugar Loaf Hill, a 50-foot-high sand dune now inside Carolina Beach State Park. The river would have a succession of names, including the Rio Jordan, to ultimately the Cape Fear River.

French navigator and explorer Giovanni de Verrazano made contact with the Cape Fear Indians in 1524. Credited with being the first European to sail to North America, Verrazano’s maps and accounts were used to plan the English colonization, including that of Roanoke Island.

Part of the Iroquois Nation, the Tuscarora Indians lived communally in bands, building villages on riverbanks and waterways. Tribal descendants make up a portion of the Tuscarora nation today.

Following the colonization of the New World by the English beginning in 1607, the southern half of this land was named the province of Carolina. In 1663, eight members of the English nobility received a charter from King Charles II to establish the colony of Carolina. These nobles were referred to as the Lord Proprietors.

Indian Wars in North Carolina 1663-1763 by E. Lawrence Lee describes the conflict brought by colonization. North Carolina saw a series of wars between the colonists and the Native Americans — the Tuscarora War (1711 to 1715), the Yamassee and Cheraw War (1715 to 1718), the French and Indian War (1756 to 1763) and the Cherokee War (1759 to 1761).

Elaine Henson was president of the nonprofit Federal Point Historic Preservation Society for eight years. In her 2006 Arcadia book, Carolina Beach: A Post Card History, Henson described the first recorded land purchase.

“On July 14, 1725, the Lord Proprietors granted to Maurice Moore a vast amount of land of which Federal Point was a part. After a succession of owners, a portion of the land was purchased by James Telfair, for which Telfair’s Creek was named,” Henson wrote.

The peninsula (it would later become an island) lying at the southernmost tip of New Hanover County that divided the Cape Fear River from the Atlantic Ocean was called Federal Point during the 1790s to honor the United States Constitution and its ratification by North Carolina in 1789.

Immediately below Federal Point, in 1761 New Inlet was created by a fierce hurricane.

By 1819, the U.S. government had built a lighthouse on the southern end of Federal Point for ships to better navigate the treacherous passage into the Cape Fear River from the Atlantic Ocean.

The peninsula had few inhabitants, mostly farmers and riverboat captains. Family names included Burriss, Craig, and Newton. The population was just 72 before the start of the Civil War, but this changed with the 1861 construction of Fort Fisher at the southern tip of the peninsula.

Guarding the river, Fort Fisher and Fort Caswell prevented Union warships from coming upriver to Wilmington. The forts protected Confederate blockade runners, which supplied Confederate troops and Wilmington residents with goods until 1865, when the fort fell to an assault by the Union Navy and Marine Corps in the Second Battle of Fort Fisher.

The fall of the fort opened Wilmington to federal occupation and a few months later the end of the war between the states. Forces occupied Wilmington on Feb. 22, 1865, following troop withdrawal toward Goldsboro and the mayor’s subsequent surrender.

The 1860 census shows eight households listed as “colored” or “mulatto.” One of these households was that of free people of color, Alexander and Charity Freeman. Alexander (1788-1855) was a Myrtle Grove fisherman in the 1840s. Alexander’s father was Abraham Freeman from Brunswick County. Many Freemans still live in that community.

“What is known is that in 1855 [the Freemans] bought 99 acres of land next to the sound and, by Alexander’s death had acquired 180 acres at the head of Myrtle Grove Sound. The land was inherited by their son, Robert Bruce Freeman, who parlayed his investment to become one of the largest landowners in the county. In 1876, Freeman and his wife, Catherine, purchased large tracts of land totaling 2,500 acres from the Cape Fear River to the Atlantic Ocean including Gander Hall Plantation and Sedgeley Abbey Plantation, which they renamed the Homestead,” Henson wrote.

The purchase was a cash sale, as no mortgage or deed of trust was recorded.

“My grandfather owned Carolina Beach in the 1800s, he was Robert Bruce Freeman,” says Freeman descendant Brenda Freeman Johnson. “Freemans came from the Waccamaw-Siouan and Lumbee Indian [tribes] from Columbus County, they were free persons of color.”

Alexander and Charity’s son, Robert Bruce Freeman Sr., inherited their acreage, in 1872, now 180 acres of land, and went about acquiring more.

The family farmed the land and fished the sounds and sea. They harvested trees for lumber and distilled whiskey. They sold granite and clay.

Freeman’s prosperity grew, amassing contiguous acreage from the Atlantic Ocean to the Cape Fear River to become one of the largest landowners in New Hanover County. His holdings were said to have reached between 3,500 to 5,000 acres, including in 1876 Gander Hall Plantation, 300 acres on the Cape Fear River, and nearby to its east Sedgeley Abbey Plantation at 900 acres.

“We lived on the Homestead, it was connected directly to the Sedgeley Abbey Plantation,” Johnson says.

A “perfectly straight avenue” lined with trees connected the mansion with the sound.

Sedgeley Abbey, constructed from coquina, had in its day been described “as one of the grandest Colonial residences of the Cape Fear,” historian James Sprunt said in Tales and Traditions of the Lower Cape Fear 1661-1896.

A coquina quarry known as Keystone Quarry was located at Gander Hall. Stone from the quarry would later be used to close the New Inlet.

Sprunt compared Sedgeley Abbey in dimensions and appearance to the two-story, cellared Governor Dudley Mansion in Wilmington. But by the 1870s it lay in ruins.

Robert Bruce Freeman donated land for a Federal Point school in the 1870s and 10 acres of Gander Hall to St. Stephens AME church for annual religious camp meetings during the 1880s and 1890s. Thousands of men, women, and children would gather at the campground at Gander Hall in 1894 for one of the largest meetings ever held, reported the Wilmington Star of June 12, 1894.

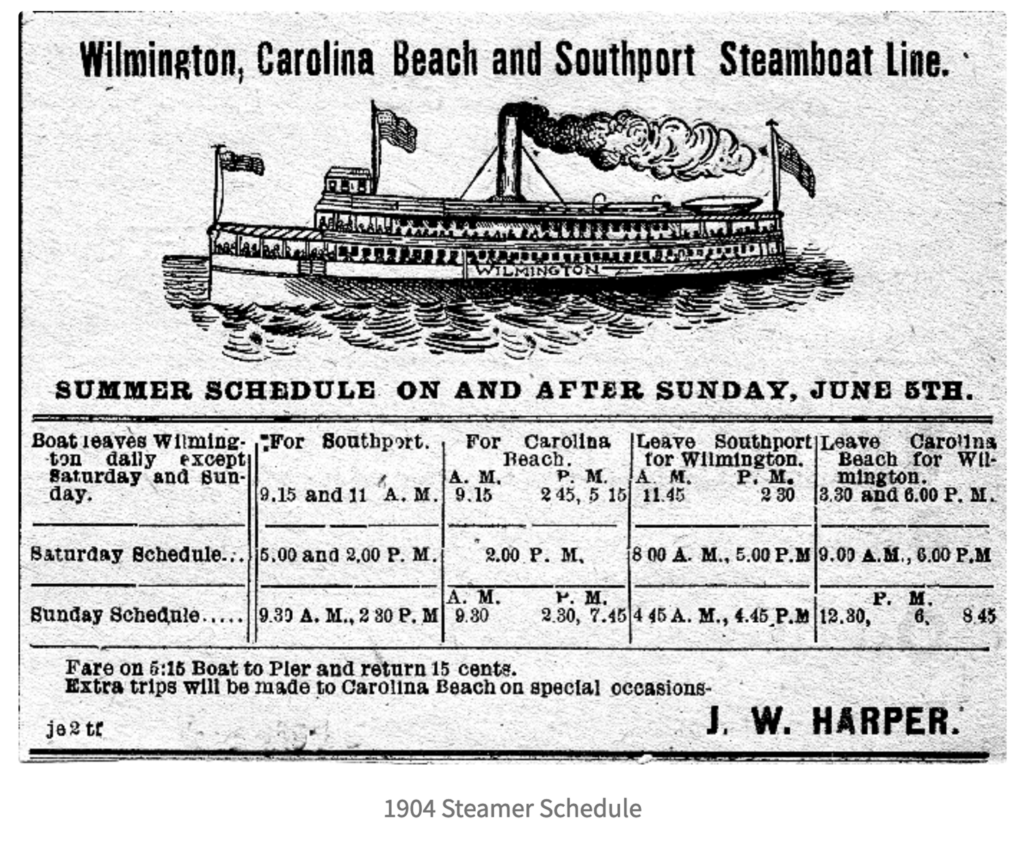

Capt. John W. Harper provided riverboat service all along the river including to and from Federal Point in the 1880s. Small cottages began to be built. Harper also began operating sightseeing and fishing trips to Smithfield (present day Southport) on his steamer Passport. Several fishermen organized the Fort Fisher Fishing Club, and they built a clubhouse near The Rocks in 1882.

“The next year, [Capt.] Harper was taking moonlight excursions there with sheepshead suppers at Mayo’s Place included in the 50 cents roundtrip price. By 1884, the Wilmington Star advertised two cottages for rent at The Rocks ‘where steamers go daily,’” wrote Henson.

One riverboat passenger was Joseph Lloyd Winner. There are several legends about how Winner first visited Federal Point. The Wilmington jeweler, originally from Pennsylvania, left a multigenerational dynasty.

Winner and his wife, Anna, bought a large tract of land at the head of Myrtle Grove Sound from the Freemans in December 1880. He laid out a resort town in streets and lots, naming it Saint Joseph.

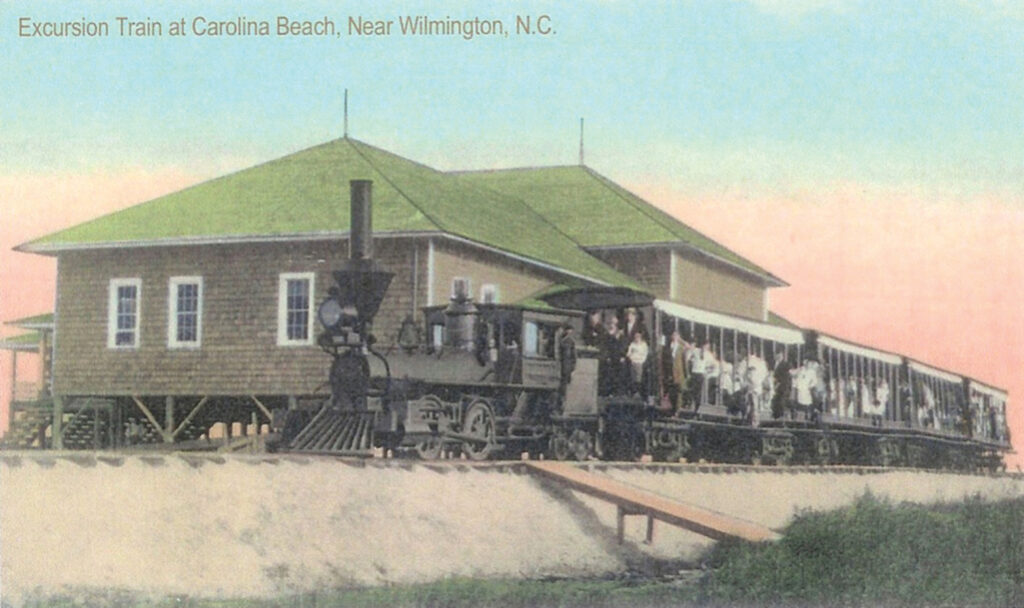

The inaccessibility of the location except by water and limited transportation once on land kept the town from taking off. This prompted Capt. Harper, William L. Smith, and others to form the New Hanover Transit Company in 1886. They purchased a right-of-way from the Winners that ran southeast from Sugarloaf across the island. The transit company began laying a 2-mile track for a railroad. Harper Boulevard today follows the path of the rail line to the oceanfront. The engine would be nicknamed the Shoo Fly.

“There are remnants of the tracks in the Carolina Beach Park today,” says Rebecca Sue Taylor, former manager of the Federal Point Historic Society.

A later track would be laid following Harper’s purchase of a bigger steamer, the Sylvan Grove, and additional land from Winner and a 24-foot strip from the Freemans. The second dock was located above present-day Snows Cut at Doctor Point or Caintuck Landing near Dr. John Fergus’s Bell Mead Plantation, west of Sedgeley Abbey Plantation.

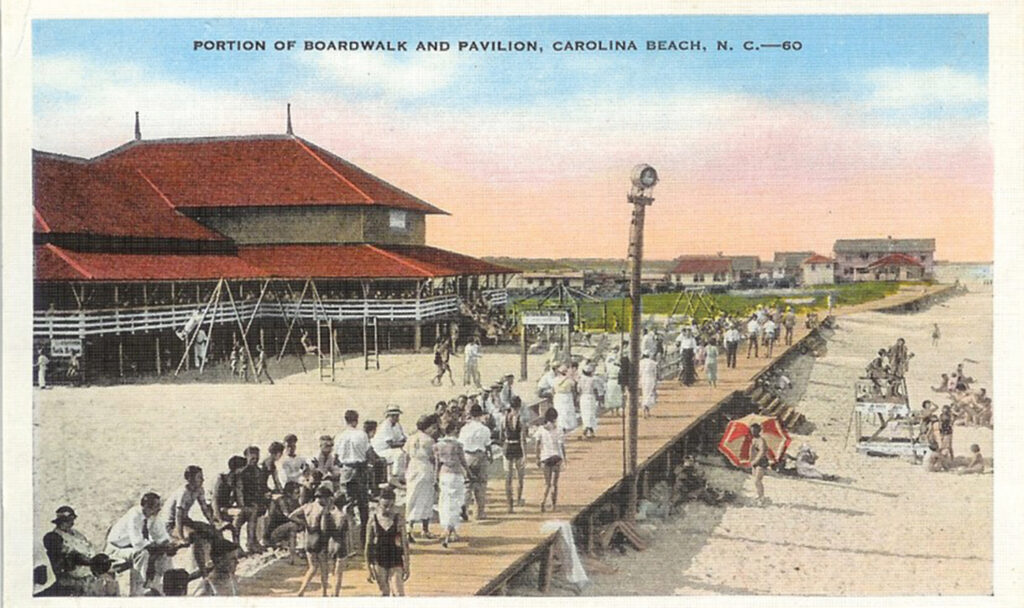

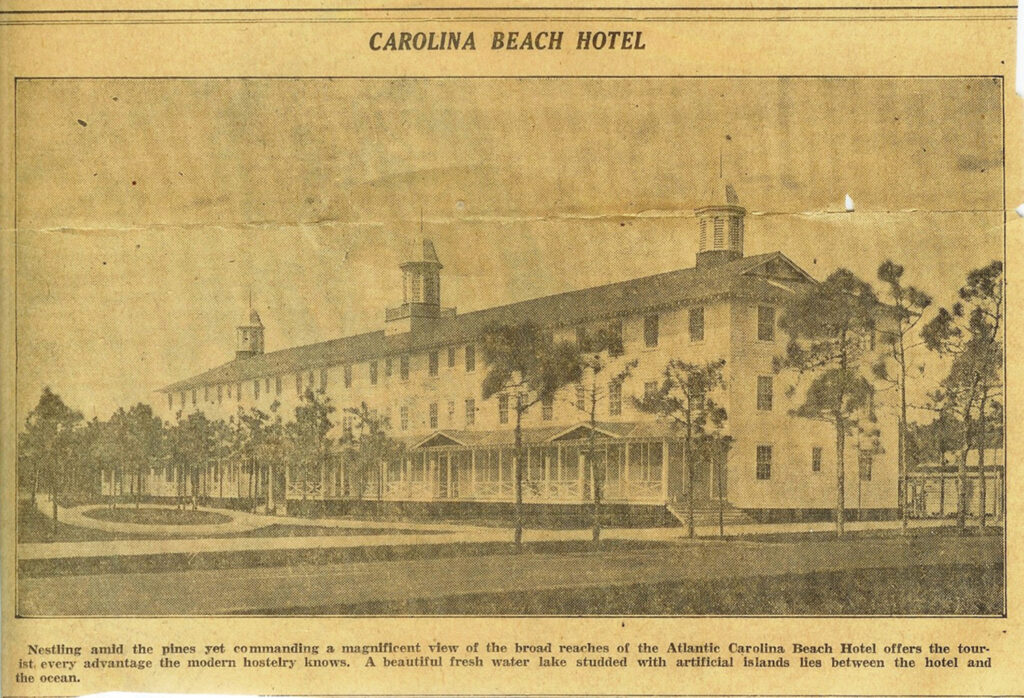

Visitors rode Harper’s steamship from a pier on Market Street in downtown Wilmington to a pier at Sugarloaf then rode the train from his riverboat to the Carolina Beach Pavilion, which was built in 1887, as was the first hotel, the Oceanic, which opened July 4, 1887. The Oceanic Hotel had a wooden walkway along the beach.

“That first summer, most excursionists came for the day using the facilities of the new Pavilion,” Henson wrote. “Those who wanted to stay over lodged at Bryan’s Oceanic Hotel and ate meals at the Railroad Station Restaurant, both barely completed. The new resort proved so popular that summer of 1887 that the 350-passenger Passport pulled a 150-passenger barge to accommodate the throngs. For the season of 1888, Captain Harper purchased a steamer, Sylvan Grove, which was licensed to carry 600 passengers. It had three decks enclosed with white railings and had salons on the main and promenade decks.”

The 1889 summer season saw construction of a windmill, a water reservoir, and new cottages, bringing the total number of cottages to 15. Nineteen more built during the 1890 season increased the total to 34. Building lots sold for $1 per foot.

Following the loss of the Sylvan Grove to a fire, Capt. Harper purchased a new steamer named the Wilmington in Delaware in 1891.

Hans A. Kure, a Danish-born man from Charleston, South Carolina, bought 900 acres between Carolina Beach and Fort Fisher. He built a billiard hall, a 10-pin bowling alley, and a grocery store in 1891.

Dance pavilions were all the rage. In his Carolina Beach, NC Images and Icons of a Bygone Era, author Daniel Ray Norris notes Sedgeley Hall Club opened March 1898.

On Nov. 1, 1899, a late-season hurricane, identified most likely as Hurricane Nine, came ashore as a Category 2 storm, destroying most of the cottages and many businesses. Flooding also occurred in Wilmington, New Bern, Morehead City and Beaufort. Wrightsville Beach saw 8 feet above normal tides. Along the coast, one steamer was wrecked and 10 smaller vessels were driven ashore.

A tornado in 1902 “destroyed the Oceanic Hotel which was no longer being used as a hotel but as a pavilion for entertainment,” Norris wrote.

In 1910, Capt. Harper’s hotel and pavilion were destroyed by fire.

“A fire destroyed the Pavilion, Kure’s Bathhouse and Smith Cottage in 1910,” Henson wrote. “That tragedy paved the way for a grand new pavilion, designed by Henry E. Bonitz, which opened the following year. In 1912, A. W. Pate and some associates bought the New Hanover Transit Company. In 1913 they added 772 acres purchased from Bruce Freeman to their holdings. The year after that they installed an electric power plant.”

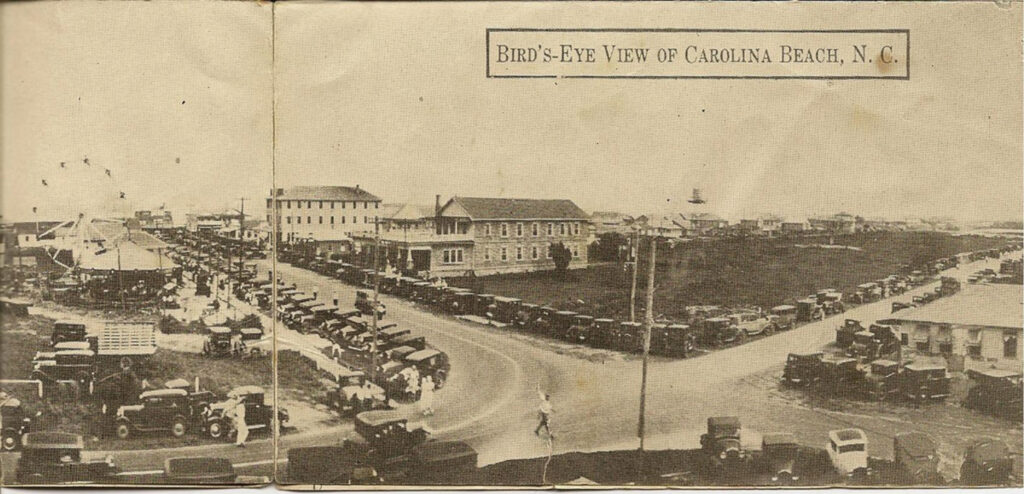

In 1925 the town was incorporated. Three years later Carolina Beach Road became a state highway.

Growth increased with automobile access in the 1930s. In 1939 Britt’s Donuts opened along the boardwalk.

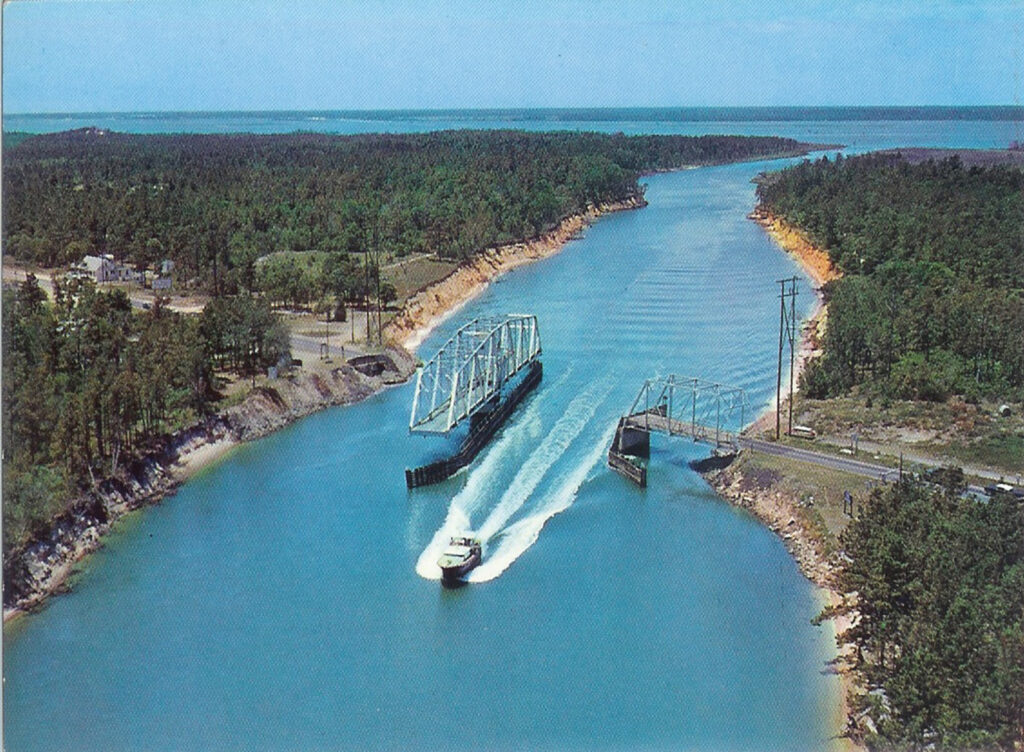

The late Susan Taylor Block described in Wilmington Through the Lens of Louis T. Moore how the Federal Point peninsula became an island with a manmade canal dug through Telfair Mill Creek and scrub oaks and woods from the Cape Fear River northeast to Myrtle Grove Sound. Originally the canal was 200 feet wide. It was later dredged to 600 feet wide.

“In 1935, Snows Cut transformed Federal Point from a peninsula into an island,” Block wrote. “The mile-long channel connects the Intracoastal Waterway and the Cape Fear River, just 15 miles north of the river’s mouth. The waterway was named for Major William Arthur Snow, an American hero who led his brigade in the Battle of Belleau Woods, France, in 1918. Even after suffering a neck wound, Mr. Snow labored 16 hours to bring all his men through the combat zone safely. Major Snow supervised the creation of the Intracoastal Waterway from Beaufort to the Cape Fear River link, completed in 1930. Locals coined ‘Snows Cut,’ but the Department of the Interior made the name official in 1944.”

A modern high-rise bridge in 1960 took the place of the steel swing bridge that opened Sept 9, 1931. A temporary wooden bridge first spanned the new waterway, the Wilmington Star-News reported on Nov. 11, 2013. Built in just 10 days, it opened in February 1930.

The boardwalk, with carnival rides, carousel, Ferris wheel, bumper cars, bingo parlors, and bowling alleys was popular. Refreshments included snowballs, cotton candy, hot dogs, candy apples, hamburgers, pizza, ice cream, milkshakes, and plenty of fried foods.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), a President Franklin Delano Roosevelt Depression-era jobs program, rebuilt the boardwalk.

“In 1934, Federal funds also financed boardwalk construction at Carolina Beach,” Block wrote.

In 1937, the late Chief District Court Judge Gilbert Burnett worked as a carnival boy on the boardwalk at age 12, selling popcorn at a snowball stand for 5 cents a bag.

“Mr. Mansfield was my boss, he owned the carnival, the Ferris wheel, the hobby horses, snowball and popcorn stands,” Burnett said in a 2015 Wrightsville Beach Magazine article by his grandson, Henry Burnett. “My job was selling popcorn. Unemployment was very high during the Depression. All kids like me — in fact all people — wanted jobs. I sold popcorn in bags about 3 inches in diameter and about 8 inches high, for a nickel.”

Burnett described Mansfield as a smart man, smart in politics and in business. Every afternoon Mansfield, a slender man who stood 5’10” tall, would have a bath and eat supper, then come down to the walkway.

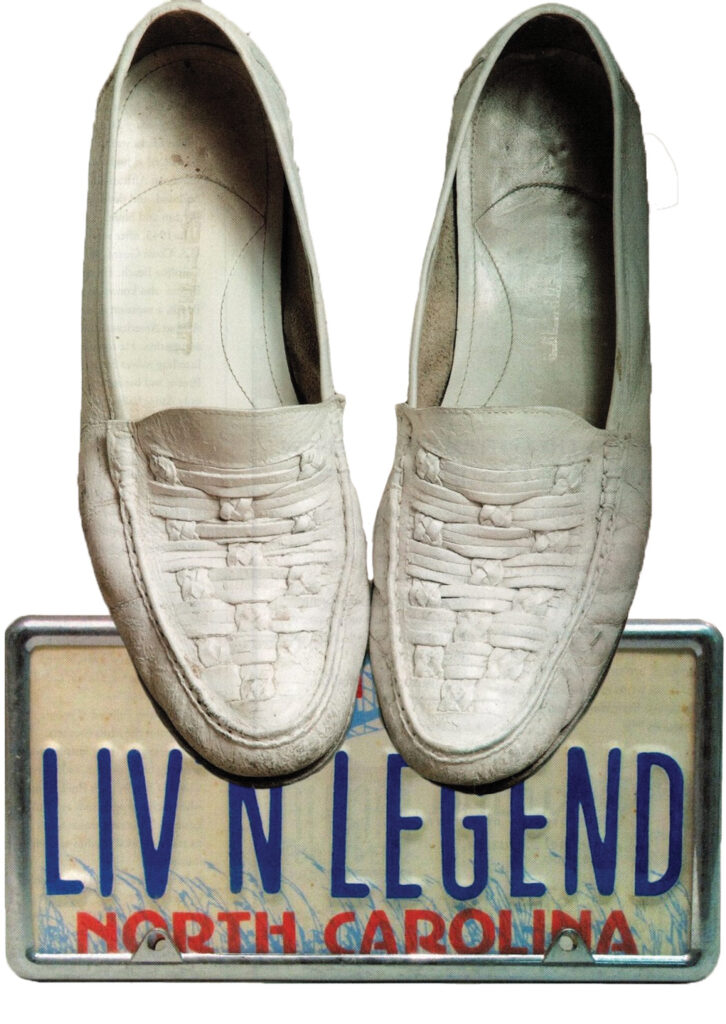

“Picture the ocean strand, the boardwalk — it was boards, not cement back then — and then the carnival. He would be dressed with white shoes. I can see him now: white socks, a white suit, black belt, white shirt, black tie, white hat with a black ribbon around the hat — a wide brim hat. He was on the town council at the time,” Burnett said.

Burnett became dissatisfied with his compensation. With no redress by Mansfield, Burnett borrowed money from his father and bought half interest in a snowball stand to go head-to-head with his former boss. Burnett’s entrepreneurial spirit prevailed and he maintained a monopoly on the snowball business at Carolina Beach until he went into the Army Air Corps in 1943 during World War II.

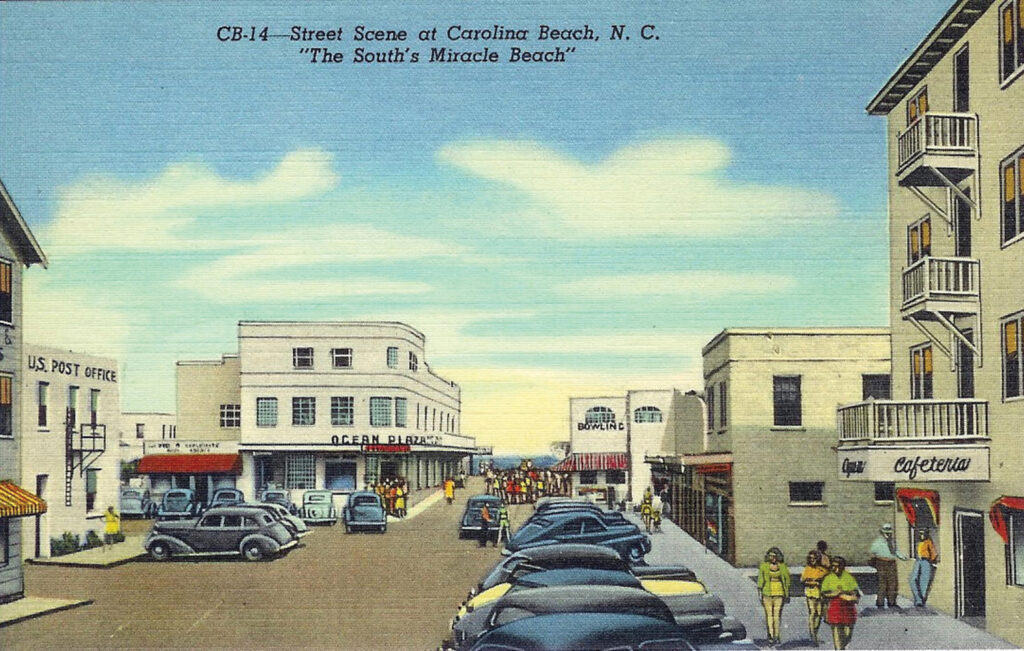

“Places with names like the Green Lantern, Cork and Sinker, Ocean Plaza, The Wave, The Landmark, Britt’s Donut Shop, Royal Palm Hotel, and the A&P all once dotted the boardwalk and the current central business district. This area was an integral part of life on the island. You could buy groceries, see a movie, shop for clothes, or eat at one of the many family-oriented establishments,” Norris wrote.

The Royal Palm Hotel, which became known as the Hotel Astor, was built adjacent to the 75-room Fountain Apartments on Harper Avenue during the winter of 1935 and 1936 by W.G. Fountain. The hotel was four stories high with 50 rooms, some with bathrooms. An additional 50 rooms were added 10 years later.

Fountain was said to only have a sixth-grade education. He came to Wilmington in 1922 from Chinquapin in Duplin County and founded Fountain Oil. He would become an alderman and mayor in the 1940s. He donated the land for a sewer system in the 1930s, started the town’s first bank, and financed the Federal Point Historical Society, the Wilmington Star-News reported in July 21, 2005. A fire destroyed the Hotel Astor on June 27, 2005.

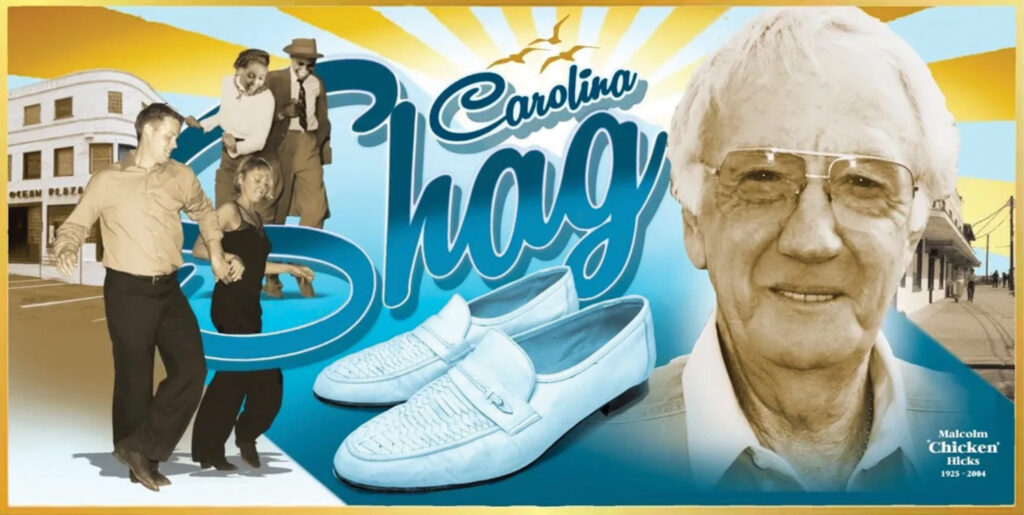

Carolina Beach’s history is probably best-known beginning in the 1940s when crowds came to dance to big bands at the hotels and in the dance pavilion. Dancing the jitterbug, bop, twist, and especially the Carolina shag would become big.

The renowned art deco Ocean Plaza was built in 1946 by Eugene and Marie Reynolds (known in the community as Mom and Pop) at the corner of Harper Avenue and Carolina Beach Avenue North. Opening May 31, 1946, where a bowling alley had been, it included a bathhouse, a café, a ballroom with bandstand on the second floor, and an apartment on the third floor. It was considered the crown jewel of Carolina Beach. Many notable big-name entertainers would perform there. For many this was the heyday of Carolina Beach. Malcolm Ray “Chicken” Hicks would popularize the Carolina shag in the 1940s and 50s.

Hurricane Hazel destroyed many of the town’s approximately 362 buildings in 1954. The Category 4 storm was particularly tough on the amusement park. Following the storm, Adolph Kaus sold the amusement park and a few rides to Carl Ferris and his family. The Ferris wheel and the carousel were centerpieces for the rides at the south end of the boardwalk.

“Carl and his wife Ruth made their home in a small cottage that was right in the middle of the park,” Norris wrote in his second volume on Carolina Beach, Carolina Beach, NC Friends & Neighbors. “The family also ran a motel, Blue Waters Court, where each room looked out over the park and its rides. … Carl Ferris’ family came from a long line of carnival and amusement park ride operators. Starting out in North Tonawanda, New York, in 1899, his family’s first carousel was mule powered. They would put a carrot at the end of a stick and let the animal go after it all day. At the end of the day when his duty was over — he got to eat it. The driving force eventually evolved to steam, gas and later to electricity, but the original spirit never diminished for Ferris. The authentic 1910 Herschell-Spillman carousel that he assembled and disassembled for carnivals throughout the first half of the 20th century made many a child happy and many a revolution since it became a mainstay of the Ferris enterprise in 1912.”

A succession of piers was built starting in 1946.

The town annexed neighboring unincorporated Wilmington Beach to its south in 2000.

The revitalization of the boardwalk began anew in the 1990s and continued into the early 2000s.

Between Sound and Sea

Freeman Beach and Freeman Park

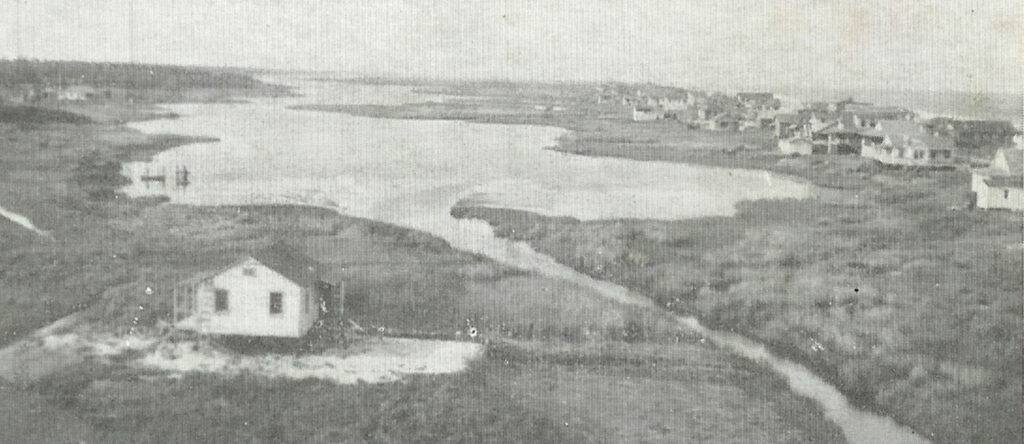

“In 1886, that spit that is essentially the north end of Carolina Beach was not considered to be that valuable to landowners who made their livelihood off the land with timber and farming,” says local historian Elaine Henson.

“The edge of the mainland was on Myrtle Grove Sound. It provided a mainland ‘still water’ beach similar to Banks Channel off Waynick Boulevard.”

“There was a strip of sand along both sides of water’s edge on the sound that could be used as a beach. But access from the black resort Seabreeze to the ocean was across the shallow sound to Freeman Beach where it was still water on one side and ocean on the other. Back in the late 1880s, it seems that the ocean was less desirable than still water for recreation, except for fishermen who braved the breakers to get out to the best fishing grounds, often over wrecks of blockade runners.”

“The purchase of the 24 acres was not that much land when considering it stretched between where the Hampton Inn is now all the way up the north end of Carolina Beach past the Carolina Beach Pier up to the tip of Freeman Park, some mile and a half to under two miles. It was a very narrow spit with the sound on one side and ocean on the other, more-narrow than it is now.”

“Keep in mind that Myrtle Grove Sound had not yet been dredged (1939) with the spoil dumped back on the land to form what is now Canal Drive.”

Twenty-four acres of the land above the high-water mark purchased in 1855 by Alexander and Charity Freeman became a park in 2004. Long used (below the high-water mark) to access the north end and ocean, it was purchased by the town in 2022.

Freeman Park, 319 acres on the north end of Carolina Beach, is open to permitted rustic camping and four-wheel vehicles, fishing, swimming, and surfing.

Acts of Community

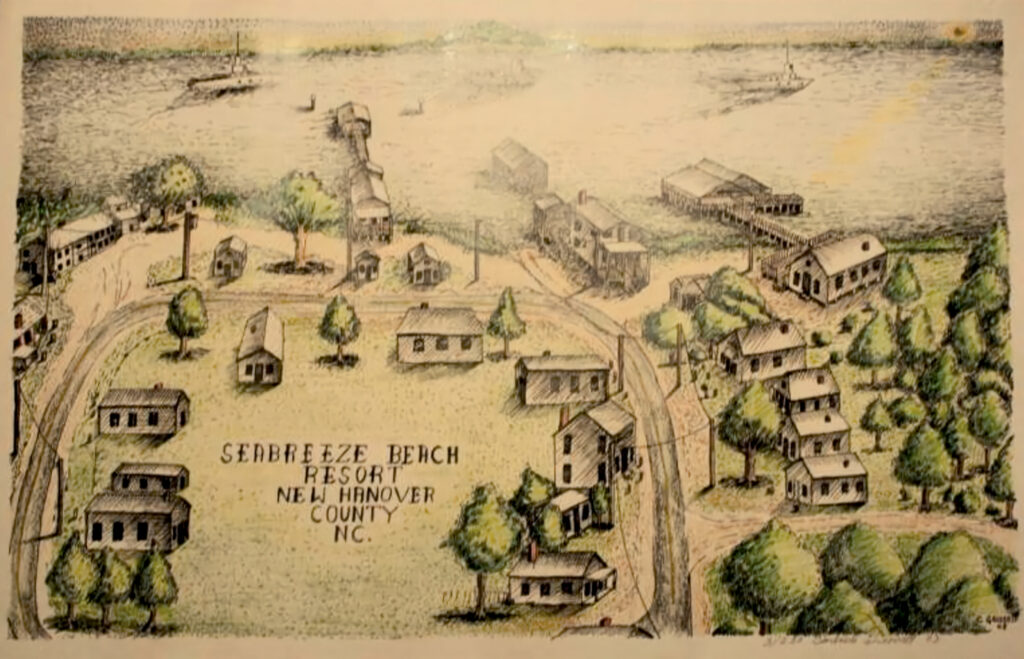

Seabreeze Beach Resort

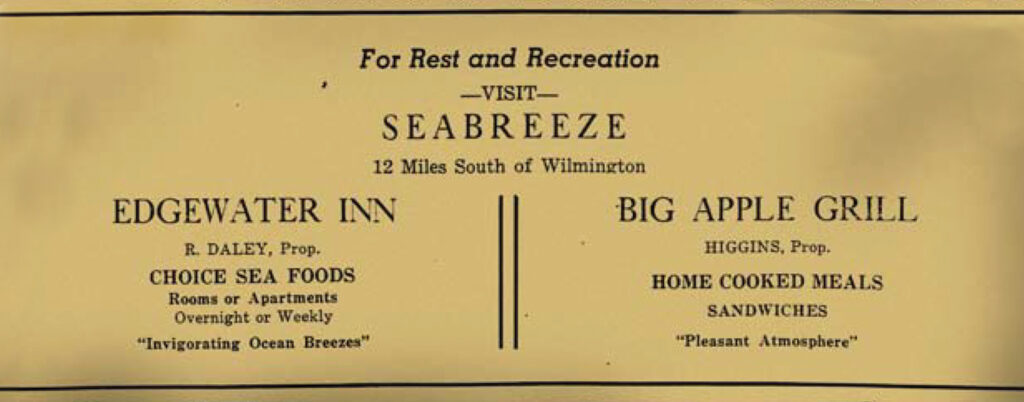

Established in the early 1900s, Seabreeze was once known as a haven for black residents and vacationers to enjoy the beach, restaurants, juke joints, and resorts without the burdens of racism. The dedication of a highway marker on May 31, 2024 celebrated families that lived, worked, and thrived in the area to include the Freemans, Davises, Wades, McQuillans, Bozmans, Rossers, and McNeills among others.

Following the 1901 death of Robert Bruce Freeman Sr. the land was divided into waterfront tracts for his heirs.

The heirs turned a portion of the waterfront acreage into a business enterprise; a black resort community they named Seabreeze.

It was a welcoming place, open for everyone.

“My father was Bruce Roland Freeman. I only know what my dad told me. He was in the Army. When he came back from the Army, he was the one who developed Seabreeze. My uncle and my cousins and my father established Seabreeze. There was nothing at Seabreeze until my dad came back from the Army between WWI and WWII. They put the money together and developed Seabreeze. My dad ran that business. It was all family, all of us worked that business,” Brenda Freeman Johnson says.

Billy Freeman, great grandson of Robert Bruce Freeman, was a child during the Seabreeze and Bop City heyday.

Pointing to a photograph of the Monte Carlo by the Sea on what is now Freeman Beach, built by Frank Hall and his wife, he says, “I worked there as a boy. I would help them pick up trash, park cars. People would drive down there through Carolina Beach.”

When segregation stopped the descendants of the first landowners of Carolina Beach from accessing their property through land their family members had sold, a ferry would take visitors from the mainland over to the legendary Bop City where the music played and the dancing commenced.

He points to another Seabreeze photograph.

“The ferry came and went from there,” he points to the structure on the left. “Not on the right, that’s Mr. Dailey’s Breezy Pavilion, the one on the left.”

“I believe the boat ride was a quarter,” Freeman says.

He was present when the inlet was opened by dynamite.

“I was there when the inlet blew up,” he says. “I tell you the water went up – the fish went up, the crabs went up. It was a lot of water.”

Oweita Freeman is the widow of Roscoe Freeman’s son James.

“He told me stories. There are so many stories out here, everybody had different experiences. Seabreeze was a jumping place, so much was going on down here,” she says.

Besides the ferry, boat ownership was key.

“Everyone down here had a boat; you had to have a boat to ride over to Bop City,” she says.

What a blast from the past — no kidding.

My family moved to Carolina Beach in ’67 as my step-father was going to Vietnam to serve his last year or so in the Army before he retired.

As a teen, I worked at the New Wave Theater running the projectors, the Putt-Putt golf course and operating several of the rides owned by Mr Ferris (all of which appear in the photos).

Lots of fond memories — seems like a lifetime ago.

Well, I guess it was.