A Developing Story

Wrightsville Beach man overcomes humble beginnings to build a successful career

BY Randall J. Williams

Some careers start with a dream. Dallas Harris’s began with a nightmare.

From his telling he was a lousy student who only graduated high school because the principal padded his transcript with unearned credits to get rid of him. One teacher said he would end up in prison, and in a way he did. It was a prison of his own making, built with bricks he laid himself.

Harris grew up in Kannapolis, North Carolina, the home of Cannon Mills. His parents spent 40 years working in those cotton mills. He had no intention of following in their footsteps. He took a different path, one that eventually led him to Wrightsville Beach and an extraordinary life of accomplishment and adventure.

Married at 18 to his 16-year-old high school sweetheart, he went right to work. After a few odd jobs he entered a tough trade, bricklaying.

By his early 20s he was traveling around the country, working for a company that specialized in building industrial smokestacks. He was good at it, and the job paid well. He got $3 an hour, double the minimum wage at the time.

Precariously perched on scaffolding hundreds of feet up in the air laying brick is a balancing act. Falling is a distinct possibility. Closing oneself into a vertical tunnel, brick by brick, all while staring into the abyss can affect a man’s mind. Harris started to have a recurring nightmare. He dreamed he was falling.

One Christmas, after completing a project in Delaware, he made a life-changing decision. He told his wife he wanted to head south. They had a small camper and a 1954 Buick Skylark. The young couple put everything they owned in the camper and hauled it to Sarasota, Florida.

They set up their little home in a trailer park on a Monday. Dallas left the next morning and didn’t return until much later. She demanded to know where he had been.

“I’ve been working,” he told her.

He found a job that day and went to work immediately. The nightmares ended, and a very different dream began to unfold.

By 1969 the couple had a son and moved home to Kannapolis. Harris was building a few houses and starting to develop land, but the savings and loan he was doing business with withdrew his credit line. He shut down his operation.

They packed their belongings into a 1955 Chevy truck and drove back to Florida, this time to Miami. Once there they shipped the truck to St. Croix, Virgin Islands.

Within days of arriving, Harris was hired as a construction superintendent on a job to build a new school. Other projects followed and he gained additional building expertise he would eventually use on a different island — one he had not yet discovered.

After five years the family — which now included a daughter — returned to America. He wanted to settle near the ocean, so he started driving up the coast and got as far as Jacksonville, North Carolina. That night, he asked his wife if she liked anywhere they had been.

“Wrightsville Beach” she replied.

“Me too,” he said.

The next morning, he drove back to the town where he did not know a single person.

Over the next 50 years, Harris would put an indelible stamp on the Cape Fear region. His life would intersect with literally thousands of people, including some of the biggest names in Wilmington.

Harris purchased a home on South Harbor Island after talking the seller into financing the deal. He built a spec house on Cypress Avenue and sold it in less than four months. He then bought two lots on Harbor Island. He met with a buyer interested in one of them. The man noticed a legal pad on Harris’s desk with a sketch of a yacht basin surrounded by lots.

“What’s that?” the man asked.

“Something I’m working on,” Harris told him.

“I want one of those waterfront lots,” the man said.

The only problem was Harris did not own the development. It was a figment of his imagination.

Seapath Towers was an ambitious project. Too ambitious, it turned out. The lender took back the land where the second tower was to be built. Harris had a better idea.

He offered the lender $350,000 for the parcel and said he could close in 90 days. The only money he had to put down was the deposit the man had given him on the Harbor Island lot. The bank took his offer. Harris put together 12 buyers for the 13 lots he designed. He called it Seapath Estates. He built his own home on the remaining lot.

Shortly thereafter, a Wilmington developer approached Harris about coming in as a partner on Shoreline at Channel Walk. The man, along with a former mayor of Wrightsville Beach, had purchased the waterfront property along Lees Cut. They needed a builder and brought Harris in to finish the project. The deal was profitable.

Harris asked about purchasing the remaining real estate along Lees Cut and the Intracoastal Waterway, including portions of what today is the wildlife boat ramp. The developer said the land was not buildable because the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had a right of way that would impede development.

“I’ll take my chances,” Harris said.

Along with two other men, he bought a small island in the ICW just north of what is known as Palm Tree Island. Their purchase was strategic. He and his partners now each owned properties affected by the Corps of Engineers easements and setbacks. They offered to donate the island to the Corps as a spoil site for dredging operations in exchange for a release from the right of way inhibiting development. The Corps agreed.

Released from the easements, Harris was able to develop Lees Cut Townhomes and marina. He donated the remaining land to the Town of Wrightsville Beach, including marshland and the parking area for the current boat ramp, an amenity enjoyed by thousands of boaters every year.

Harris was on his way to becoming a major developer. His advantage was that he understood construction as well as land development.

This expertise attracted the attention of a couple of investors who owned property west of the Wrightsville drawbridge. They enticed Harris to come in as a partner and be the general contractor for a condo/townhouse project they called Wrightsville West. It was a big success.

With that as a springboard, Harris and his new partner purchased a large portion of the old Pembroke Jones estate across from where Landfall is today. They developed the townhome community of Lions Gate, a name Harris chose as a nod to the history of Pembroke Jones, who had built gates on that property with marble lions on top. The gates had been vandalized over the years. Harris claims a lady at Wrightsville Beach offered to sell him the head of one of the lions for $3,000. He declined.

Lions Gate was a bust. They built more units than the market could absorb. His partner bowed out of the deal and Harris finished the project.

He didn’t make much money, but he had momentum. He had cash, he had credit, he had good subcontractors, and he had a growing following of loyal customers who were buying into everything he touched. More opportunities were coming his way than he could handle.

He negotiated a deal to buy Landfall but backed away. It was too large a project, with the potential to bankrupt him. He and a partner designed a 10-story building and marina along Airlie Road that the city of Wilmington ultimately ruled against permitting. He declined an opportunity to purchase a small section of Barefoot Landing, a large golf course community in Myrtle Beach, because he didn’t “want to be a little fish in a big pond.”

After Lions Gate, Harris purchased an adjacent parcel of land and built the patio home community of McCumber Terrace. He bought and demolished an old motel on the south end of Wrightsville Beach and developed the Surf Motel, where he coined the term “Motelominium.” It was a novel concept, a condominium that functioned as a motel. He finished it in a few months using a patented concrete form system he had learned while building apartments in St. Croix. He closed all 45 units one morning at an old restaurant in Wrightsville Beach over coffee and donuts, where buyers lined up with certified checks as their attorneys prepared the paperwork.

He developed a similar project overlooking Banks Channel called Summer Sands. The concept was so successful that other developers emulated his plan. More projects followed, including Hanover Arms, Eastwood Village, Sea Spray, Pebble Cove, and Rock Port. He started a 700-unit community called West Bay but eventually sold to another developer for $15,000 per unit.

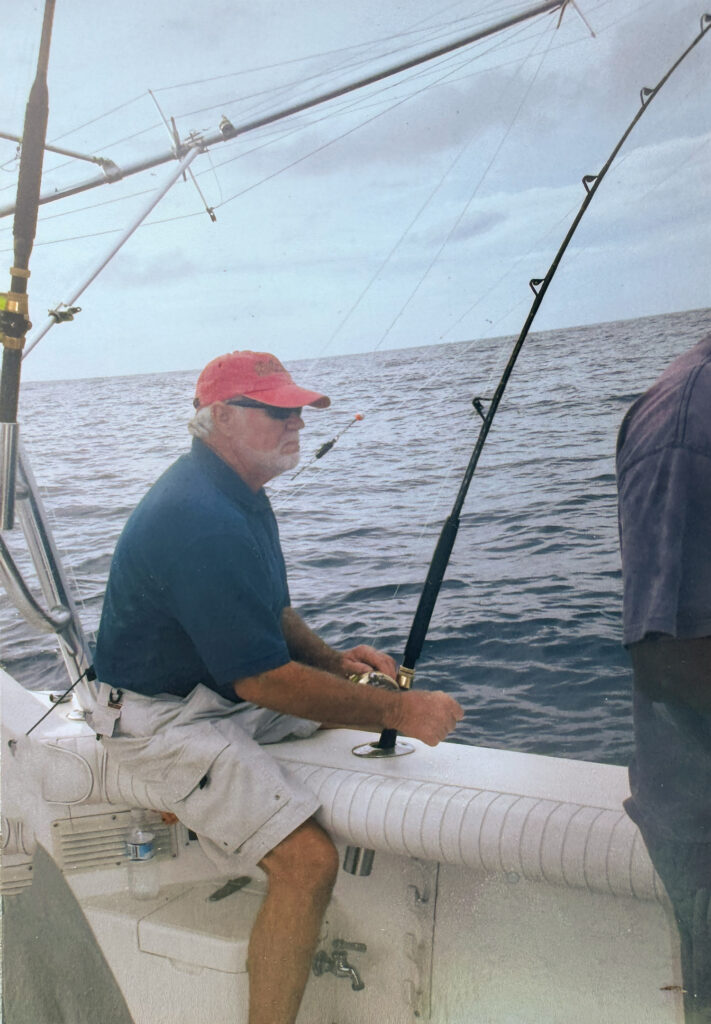

With money comes toys. He bought airplanes and yachts. He traded a house for a 48-foot sailboat. He didn’t have a clue how to sail, but soon learned. He motored out Masonboro Inlet one day and “put up the sails to see what she would do.”

With trial and error, he learned how to navigate, anchor, moor, dock, read the weather, work on equipment, and pilot a boat in almost any type of sea. Eventually he became a first-class yachtsman.

Once while docked in Charleston, the most famous anchorman in American broadcast history stopped by to see his boat. The man was interested in having a similar one built. He and Harris became friends and made several sailing trips to Florida together.

He next bought an 83-foot Broward motor yacht named Monkey Business. Political aficionados may recall a certain U.S. senator torpedoed his presidential aspirations in 1988 when photographed during an unpropitious moment aboard that aptly named vessel. Harris says he sold the boat to a Bahamian drug dealer.

“He owned a whole island in the Bahamas,” Harris says. “Everybody on the island worked for him, and once you went to work for him, you never left.”

Harris bought a larger yacht and sailed it to Newport, Rhode Island, to rendezvous with fellow Broward owners he and his wife met at a marina at the base of the World Trade Center. He captained the 90-foot boat himself, with his wife as his only mate, much to the surprise of his fellow skippers.

After that he took on an audacious project. He purchased a 100-foot aluminum “crew boat” and spent $2 million refitting it in Morgan City, Louisiana, utilizing a talent pool of shipwrights he says were among the best tradesmen he ever worked with. The ship had six state rooms, six heads, a large salon and galley, and a bar and hot tub on the top deck. She carried 10,000 gallons of fuel, including 1,000 gallons of gas he used to power a Ford Excursion and two Harley Davidsons stashed in the hold, along with two large dinghies mounted on the 35-foot clear span stern deck. He named her the Sea Holly after his first daughter.

He left Louisiana with the boat complete except for the woodwork. The shipwrights went with him as far as Key West, finishing the carpentry before driving back in a van he rented for them.

“So long, boys,” he said. “I’m heading to Cuba.”

And off he sailed, manning the helm himself.

By then Harris was twice divorced. While in Cuba he did what rich American men have always done in that ruined paradise — fish, drink and seek beautiful women.

He surrounded himself with a cast of characters right off the pages of a Carl Hiaasen novel. Wealthy friends came and went, but he also spent countless days with poor fishermen.

Some of what he did in Cuba he keeps to himself, but there are stories he will tell. He was detained one evening by a dozen armed men after attempting a shortcut back to the harbor. Apparently, he ventured too close to one of Fidel Castro’s compounds. After checking him out, they released him, and suggested he not come back that way again.

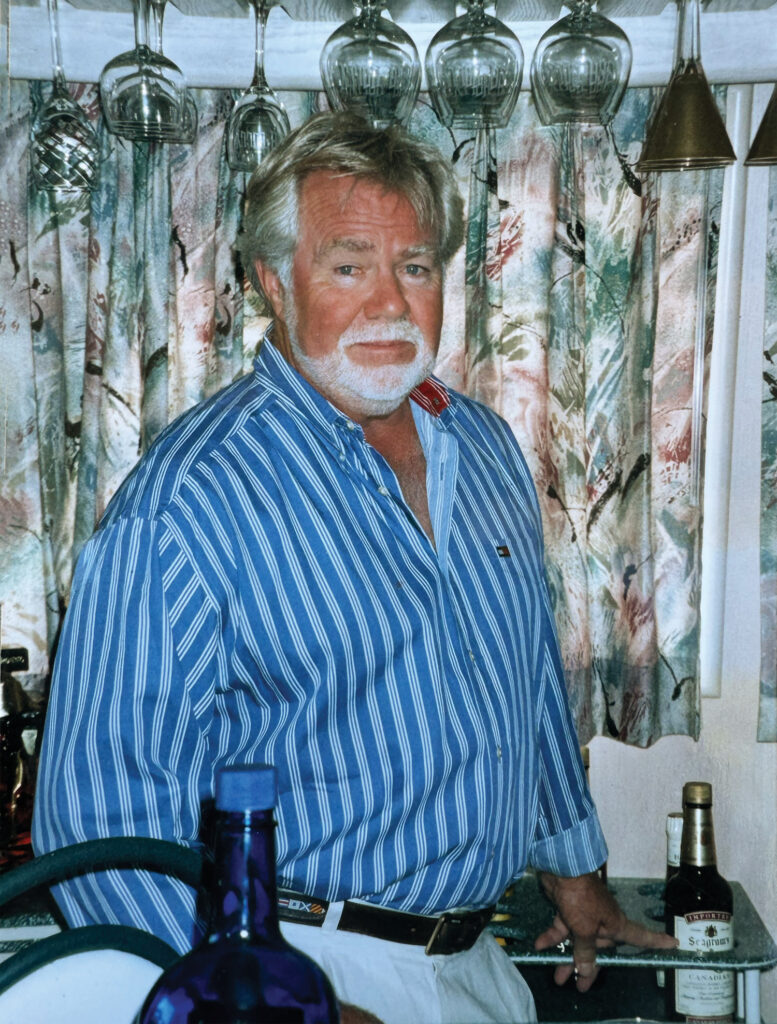

Harris is a handsome man. Many people have suggested he looks like a cross between Kenny Rogers and Ernest Hemingway. With his distinguished white hair, he looks more like Hemingway these days, a man whose home he visited while in Cuba. The Communist curators of that confiscated shrine allowed Dallas to view Hemingway’s boat, the Pilar, which he found spartan and modest compared to the machismo of her erstwhile captain.

Harris has outlived Hemingway by a quarter of a century. Like Hemingway, he loved the Cuban people, one in particular — a young woman he ended up marrying. When he left Cuba he took her with him, and they sailed away towing a 40-foot sport fisherman all the way to Panama. They’ve been together over 20 years now and have a beautiful 15-year-old daughter.

Eventually Harris shut down the construction side of his business. Many of the men who were such an integral part of his operation had moved on, retired, or died. But he continued to develop land.

He purchased around 600 acres in Pender County near the Northeast Cape Fear River. He put in a boat launch and horseback riding trails and sectioned it into parcels no smaller than 10 acres. This he named Equine Acres and sold every lot he had, saving one for himself where he built a personal residence.

In 2018 Hurricane Florence made landfall a little south of Wrightsville Beach. Over the next several days 30 inches of rain fell. Land that had not flooded in living memory went underwater, including Equine Acres and much of N.C. Highway 210, the main road in and out. Harris drove his backhoe through the floodwaters, commandeered a boat and herded a neighbor’s livestock to high ground. He was 81.

Developers burn a different type of fuel. They are risk takers and adventurers. They dream big and sometimes they crash, but unless it destroys them, they do it again.

They live in a world of debt. Quizzed if he made money on a particular project, he says, “I don’t really know. The bank was charging me almost 20 percent interest. It was like being on a railroad track with a locomotive behind me. I didn’t look back, just kept moving.”

Most have gone through cycles of boom and bust more than they care to recall. That lifestyle can be tumultuous. Sometimes collateral damage follows in their wake.

Harris is no exception. Partnerships emerged and fizzled. Professional relationships sometimes frayed. Friends came and went. He has outlived many of his contemporaries.

His marriage to his high school sweetheart, the mother of two of his children, now 50 and 62, came apart. Eventually he remarried, divorced, and married yet again. But he kept moving.

Over the years Harris met and befriended many wealthy and famous people, but he has always loved the working man. They are his people. Plumbers, electricians, carpenters, mechanics, roofers, real estate brokers; there are people all over the greater Wilmington metro who in part owe their professional success to Dallas Harris.

In return, he states emphatically that he could not have done it without them, giving particular credit to a lender, an architect, a surveyor, and a road grader who worked on almost every project he did. There are plenty of folks outside the industry he has quietly helped as well.

“Sometimes a small favor from you can make a big difference to someone else,” he says modestly, without any expectation of reciprocity.

But he is most appreciative of the thousands of folks who bought into his developments. Without their support, he would not have enjoyed the professional success he has.

Harris has a talent for sizing up a piece of land. He can tell you what direction the water runs off, how to grade it, where to build the ponds and roads, what trees to save, which ones to timber, and if what’s underneath has any mining value. Over the years he has owned excavators, bulldozers, backhoes and tractors. He knows how to operate all of them.

Today he and his wife live in a home he built on a tract of land that backs up to Holly Shelter. The Holly Shelter Game Lands consist of over 60,000 acres. Harris would develop it all if they would let him.

On any given day you might find him sitting on his tractor, riding alone, enjoying the sunshine and smelling the pine trees and the freshly plowed soil. At 88, he is about as far away from falling down a brick smokestack as a man can be.

A great article about a wonderful person and friend. I enjoyed very much reading about Dallas’ life in and out of construction. Tenacity, fortitude and vision describe Dallas so well!