A Covey of Memories

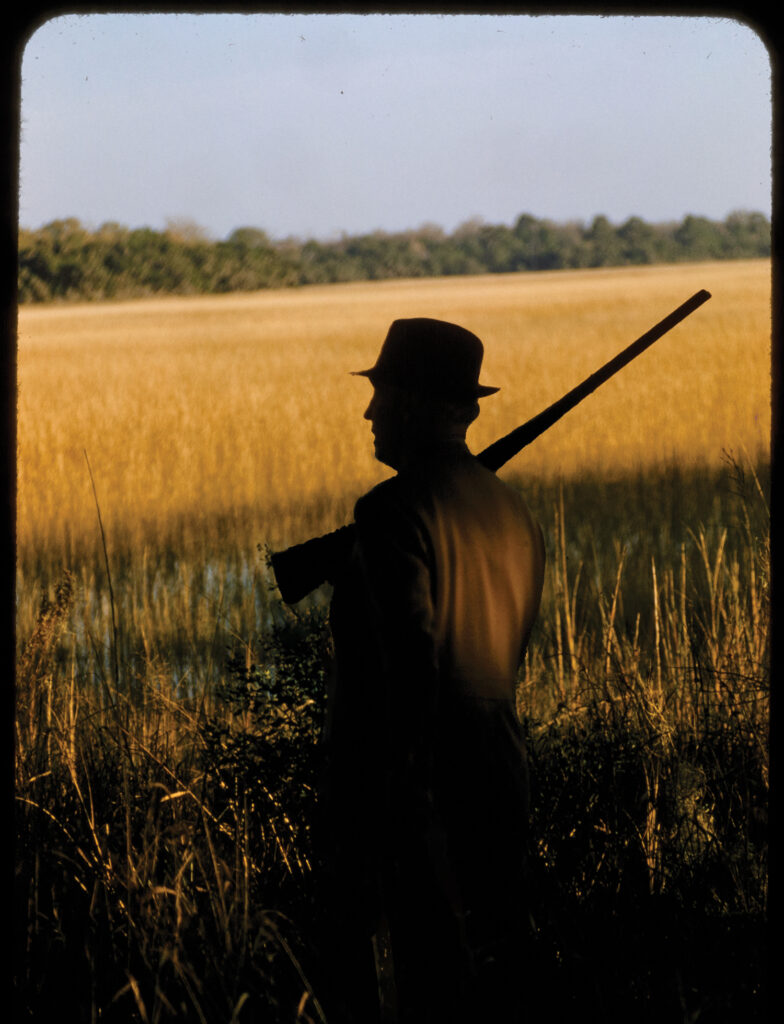

Ten coveys, two setters, and a magical farm combine for a quail hunt to remember

BY Robert Rehder

There were quail back then, big coveys, especially on the coastal plain. Forged by a thousand years of dodging predators, quail were wild, smart, and plentiful. They flushed like bullets and usually placed a stump, branch or tree squarely between you and their tailfeathers.

In the South, quail were known as birds so if you were going bird hunting, it wasn’t for dove or woodcock or duck — you were hunting quail. You learned to shoot fast and hard and be prepared to come up blank. Strong legs, sturdy boots, a bird dog worth half his salt, an open-choked 20-gauge shotgun and you were in business.

Coveys found food in garden patches where beans and peas were scattered after a summer crop. Dense forest floors were burned, offering open lanes and new growth. Farmers left grassy hedgerows and strips of brushy covers for crickets, June bugs and grasshoppers, which fed the spring broods. Wild seeds and berries grew along field rows for quail, doves, bees and songbirds. When coyote or fox came calling, birds flushed into the nearest catclaw briar patch safe from harm.

Times have changed, and now it’s rare to even see a covey of wild quail or to hear the lovely Bob-WHITE call ringing through the fields. It’s even harder to find hunters who can recall and describe those days. Yet the memories of yesterday still flow over those peaceful, rural places where the birds once lived, and I vividly recall a hunt from many years ago.

Most quail hunts start in a field, but this one started in a country store.

It was the Christmas holidays and a cold, bitter spell of freezing rain made bird hunting practically impossible. The winter storm finally blew over, and I knew the birds would be moving.

Eager to get outside, I had my setters in the truck on my way to hunt familiar places during the afternoon. I happened to pass an old country store. I would not have stopped, but then I saw the flowing patchwork of grain fields and hedgerows stretching out behind the store. It looked like quail heaven, so I pulled into the muddy lot.

Two old men dressed in overalls sat playing checkers on the sagging front porch. One spat tobacco over the rail and onto the dirt as I approached.

The huge front door looked like something from an old horror movie. It creaked and groaned as I opened it. Inside, dusty shafts of sunlight fell across a smooth, hand-worn counter that stretched the length of the room. Blue denim, jars of pink pigs’ feet, rubber boots, nails, peppermint candy and a hoop of yellow cheese were stacked on the counter. The pungent scent of rope, leather and tobacco hung heavy in the air.

Suddenly, the soft light illuminated a striking face behind the counter that made me catch my breath. Her oval face was tanned and lined and framed in thick blonde hair woven with ribbons of gray. Leaning out over the counter, she talked to a customer, but then her unblinking gaze caught my eyes and held me as if in a trance.

She turned suddenly, her hazel eyes flashing in the pale, dappled light, never releasing me from her stare. “I’ll be just a minute,” she said. I managed to mumble something of a reply. Her complexion was bronzed, her freckled face set with high cheekbones and lovely, chiseled features.

She finished talking to the customer and turned to me, her eyes bright and compelling, and asked, “How can I help?”

Stunned by her beauty in such a cheerless place, I stammered, “I wondered if you owned the land behind the store, and if I might hunt quail there?”

“Is it just you?” she asked.

“Yes, I’m alone,” I said, “and I have two setters.”

“I’ve never posted my land, and I’ll let you hunt back there just today, but I have chickens that roam around the back, so stay away from the store and keep your dogs away from my chickens,” she said rather fiercely.

“Yes, I will, thank you,” I replied.

I turned and started to leave but the last glimpse of those compelling eyes stopped me cold once again. Searching for words, I asked, “So you also farm this land?” “Yes, I farm the land, fourth generation, and I’m busy running a business, so don’t make it a habit stopping by asking to hunt,” she said, again rather directly.

“Yes, of course,” I replied, knowing that I would be back.

“Have you seen any quail?” I asked before heading out toward the two old men guarding the front porch. She sighed, looked irritated, and finally said, “Yes, the dirt path behind the store leads to some hedgerows that you can hunt down toward 40 acres of new-ground that border the river. Twenty acres are in cut soybeans and 20 in longleaf pines that I put in two years ago. We saw some coveys in the new ground while picking beans last month.”

“Thank you, you’re very kind,” I replied.

Her face softened. “Stop by on your way out and let me know what you found.”

It was afternoon when I parked my truck out of sight behind a thick, thorny hedgerow of tangled sedge and blackberry. I put extra shells in my hunting coat and released the setters, whining and yipping, exploding from their boxes.

I hunted into the wind down a series of adjoining paths and over a rise that dropped off to the new-ground in the distance. The day was bright and cold with a heavy frost that made the fields wink and sparkle in the sun.

We came around a bend that bordered a harvested soybean field and the dogs suddenly froze like statues, eyes wide, noses full of quail scent, pointed toward a thick tangle of gallberry. I walked into the covey and cleanly missed on the first quick shot. I was only yards from the truck and already in birds. It was a big covey and the dogs ranged ahead pointing singles farther down the hedgerow.

On a point in a clutch of lespedeza I fully expected a single bird, but it was a full covey that played their old trick of letting me walk right past them. I heard wings frantically whirring behind me, and I turned too late, almost falling over backwards, to see the whole covey sail untouched into the new-ground pines.

The farm was clean, neat, and well cared for, and as the afternoon wore on, I worked through one beautiful quail cover after another finding coveys and singles almost everywhere. There were forest edges, ridges, creek bottoms, swales, and soybean stubble. The last hedgerow led to a briar wall along the forest where birds came from the woods to feed. The dogs pinned two coveys there for quick shots before they flushed back into the trees.

There were many days that year when I couldn’t find birds, but not that day, and the magic had one more turn of good luck for me.

I still had had a good hour of sun, so the dogs and I circled back out to find singles in the new pines. We were a hundred yards in when I saw one of the setters on a hard point ahead. I fully expected a single quail, but at the last possible second, the largest covey I had seen all year, at least 20 birds, erupted from just under my feet. The thunder of wings utterly unnerved me, and I didn’t even shoot until a late bird finally rose.

We followed the covey, and the setters cornered more single birds. Soon I had my limit, and the hunt was over. The scent conditions were perfect that day, and the dogs and I had found an amazing 10 coveys.

It was growing dark as I made my way back to the truck, the brave setters at my side, the coveys softly whistling back together in the twilight. It was getting colder. I could see the lights of the old store up on the hill blinking in the distance.

A blue and lavender sunset hovered over the western sky. A mist rose over the fields that stretched out before me. The rising moon cast a pale hue across the great forest and the dark, moving river. The day, the place, still burns in my memory — the strange, wild, lonely charm of a time I knew was vanishing.

The store is closed and boarded these days. The farm is leased, and the fields are laid out by computer in perfect rectangles. Every square foot of land is efficiently planted. The hedgerows and covers of native grasses have all gone to crops. In one of wildlife’s great tragedies, the coveys of wild quail have vanished from the farm, and indeed from the South.

But amid the somber farm buildings, a neat, charming cottage remains, surrounded by a meadow of wildflowers, a quiet remembrance of things past. The cottage has a gabled roof, a stone chimney, and a covered porch with flowing, hanging baskets. There’s a brick pathway that winds through a mystical garden that blooms in glorious, colorful waves where bees and songbirds thrive.

If you’re passing that way, you might see her there on warm days when the wind is gentle from the south. She’s frail now, her hair is silver, and she walks with a cane, but when the morning sun strikes her face, her soft, hazel eyes still sparkle, and she is as lovely and beautiful even now as when I first met her in the ancient store so many years ago.