Home Surf and Turf

JENO

prepares

a struc-tured

plan for local

teams, easing

them in with

workouts that

last around one

hour. Gradu-ally,

she builds

them up to

12-mile runs

and 3-mile

swims that take

up to four hours

to complete.

For athletes

like the Double

E’s, routines

may change based on the race they take on. But SwimRun or not,

they’d still be coming together six days a week to train.

Local athletes take advantage of Banks Channel and the Intra-coastal

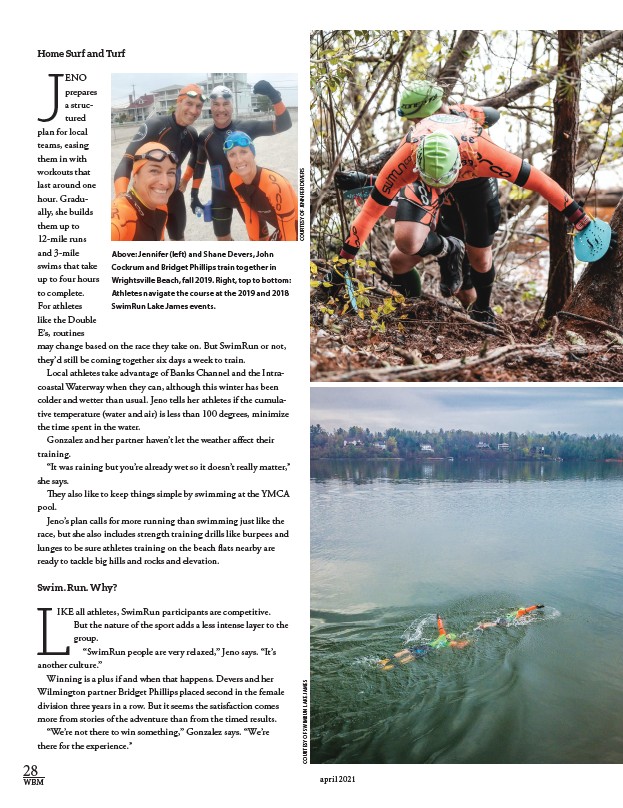

Above: Jennifer (left) and Shane Devers, John

Cockrum and Bridget Phillips train together in

Wrightsville Beach, fall 2019. Right, top to bottom:

Athletes navigate the course at the 2019 and 2018

SwimRun Lake James events.

Waterway when they can, although this winter has been

colder and wetter than usual. Jeno tells her athletes if the cumula-tive

temperature (water and air) is less than 100 degrees, minimize

the time spent in the water.

Gonzalez and her partner haven’t let the weather affect their

training.

“It was raining but you’re already wet so it doesn’t really matter,”

she says.

They also like to keep things simple by swimming at the YMCA

pool.

Jeno’s plan calls for more running than swimming just like the

race, but she also includes strength training drills like burpees and

lunges to be sure athletes training on the beach flats nearby are

ready to tackle big hills and rocks and elevation.

Swim. Run. Why?

LIKE all athletes, SwimRun participants are competitive.

But the nature of the sport adds a less intense layer to the

group.

“SwimRun people are very relaxed,” Jeno says. “It’s

another culture.”

Winning is a plus if and when that happens. Devers and her

Wilmington partner Bridget Phillips placed second in the female

division three years in a row. But it seems the satisfaction comes

more from stories of the adventure than from the timed results.

“We’re not there to win something,” Gonzalez says. “We’re

there for the experience.”

COURTESY OF SWIMRUN LAKE JAMES COURTESY OF JENNIFER DEVERS

april 2021 28

WBM