Illuminating the Past

BY Simon Gonzalez

Lighthouse enthusiasts have a couple of options here in the Cape Fear region. They can visit Old Baldy on Bald Head Island and the Oak Island Lighthouse at the mouth of the Cape Fear River in Brunswick County. The Cape Lookout Lighthouse at the southern tip of the Outer Banks isn’t too far away either.

But there isn’t an operable lighthouse in New Hanover County.

“People love lighthouses. We get a lot of visitors who ask ‘Hey is there a lighthouse here?'” says Becky Sawyer collections manager and exhibits coordinator at the Fort Fisher State Historic Site. “No you’ve got to go to Bald Head or Oak Island.”

That hasn’t always been the case. From 1817 to 1880 three beacons stood on or near the current Fort Fisher site. They were called by different names: Federal Point Beacon Federal Point Beacon Light New Inlet Lighthouse Federal Point Lighthouse Fort Fisher Light. They served the same mission: to guide mariners through storms or dark nights to the mouth of the Cape Fear River.

In September 1761 a hurricane cut an inlet across the Cape Fear Peninsula. New Inlet (apparently the people who bestowed geographic names in the 18th century lacked imagination) became a shortcut from the Atlantic to the Cape Fear River allowing mariners to avoid the treacherous Frying Pan Shoals. But the new passageway wasn’t without its own risks. In 1798 citizens on Federal Point asked for a beacon to safely guide ships to the new passageway. Congress approved $1 800 for the project but it would be a few years before any action was taken.

The first navigational aid to New Inlet came about because of the second conflict between the United States and England.

“Everybody knows Fort Fisher was built to protect New Inlet [during the Civil War]. But they realized as early as the War of 1812 that there needed to be some type of defense on the point ” Sawyer says.

Troops were sent from Raleigh to strengthen the coastal defenses and build a fort and battery. The war with England lasted from June 1812 until February 1815. The only skirmish off the Carolina coast occurred in July 1813 when the British raided Ocracoke Inlet. The Federal Point cannons weren’t needed to fire on the enemy but they became a landmark in peacetime.

“The battery and the barracks were used as a navigation aid to get into New Inlet in 1815 and 1816 ” Sawyer says.

Still there was a need for something more and on Sept. 15 1816 Benjamin Jacobs was awarded a $1 300 contract to build a light that was “40 feet high and conical in shape.” A beacon light with eight working lamps was completed the following year. It remained operational for nearly 20 years before it was destroyed by fire on April 13 1836. [Because of constant erosion before the oceanside rocks were installed the topography of the peninsula has changed but the light stood near where the historic monument is today.]

Eleven months later Congress approved a bill for improvements to lighthouses. Included was $5 000 to rebuild the Federal Point light. The new beacon was operating by February 1838. It was painted white 18 feet in diameter and 46 feet tall. The light was visible from up to 12.1 miles away.

Like its predecessor the new light was not destined for permanency. It was beset with problems from the start and frequently needed repairs. An 1851 report from the Lighthouse Board noted its poor condition.

At the onset of the Civil War in 1861 North Carolina Gov. John W. Ellis ordered all of the state’s coastal lights to be “destroyed rendered inoperative or have their lanterns removed.” The Federal Point beacon was demolished.

The lighthouse was gone but the facility did play a role in the conflict. The lightkeeper’s house became the headquarters for Confederate Col. William Lamb when he became commander of Fort Fisher on July 4 1862. But even that was lost when it was intentionally destroyed by Union shelling on Dec. 24 1864.

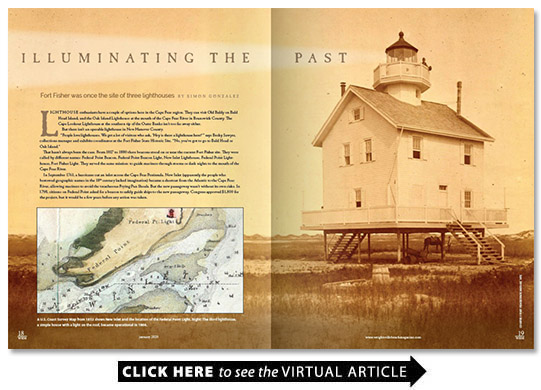

The third lighthouse was constructed a year after the Civil War ended and became operational on April 30 1866. It was a simple structure a two-story house with a light apparatus on the roof. The beginning of the end for the final beacon came in 1872 when the Corps of Engineers recommended the closure of New Inlet to prevent sand from washing into the Cape Fear River.

To the federal government the closing of the inlet negated the need for the lighthouse but some locals disagreed.

“I was at the National Archives this summer and I found a petition by the ship owners and various merchants to keep the lighthouse still lit ” Sawyer says. “They said we need something because there’s no light from Cape Lookout to Frying Pan Shoals.”

The effort failed. Old Baldy was relit in 1879 after being darkened during the Civil War. Sawyer speculates that Congress didn’t want to allocate more money toward repairs and maintenance for a small dilapidated lighthouse just a few miles up the coast.

“The light was in poor condition at the time ” Sawyer says. “They had not been making repairs to it since 1875 when they started to close the inlet.”

The lighthouse went dark on Jan. 1 1880 when the lamp was removed. The keeper’s cottage remained for a while.

“They let Mr. Taylor who was the lighthouse keeper stay in it ” Sawyer says. “Looking at the 1880 census records it looks like he was running a store out of it.”

But it too was lost to history when it was destroyed by fire on Aug. 23 1881.

The tale of the three lighthouses is a little-known piece of local lore but Sawyer suggests it’s a story worth telling.

“We’re known for military history but this is our local history ” she says. “It’s local history it’s archaeology it’s material culture. It’s all of those things. It also comes full circle. The acre plot for the lighthouse in 1817 and 1837 becomes Battle Acre in the 1920s which is basically the genesis of our historic site and the monuments over there.”

Visitors to the Fort Fisher Historic Site can learn more about the lost lighthouses through an exhibit curated by Sawyer and installed in January 2019.