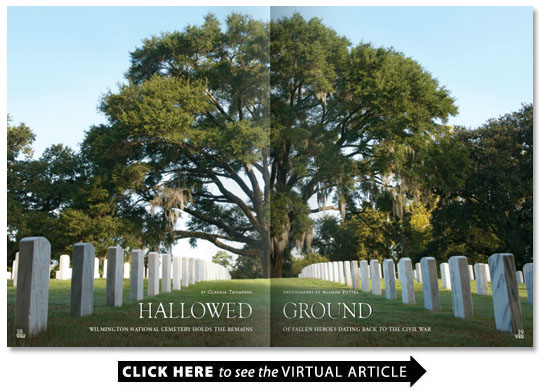

Hallowed Ground

BY Claudia Thompson

In 1862 Congress responded to the mounting number of Civil War casualties by granting President Abraham Lincoln the power “to purchase cemetery grounds � for the soldiers who shall die in the service of the country.” Thus the national cemetery was created.

The Wilmington National Cemetery was established in 1867 and is recognized as a Civil War-era cemetery by the National Register of Historic Places. Initially only those who fought for the Union — often just referred to as “the North”– were granted burial. A few were reinterred from states below the Mason-Dixon Line but those were prisoners of war held by Confederate troops and include a handful of defectors from Tennessee.

Through the years the cemetery landscape reshaped to include other U.S. wartime dead and veterans such as the African-American regiment known as the Buffalo Soldiers from the 9th Cavalry who fought in the Indian Wars from 1866 to the early 1890s. There are casualties from the 1898 Spanish American War and a group of Puerto Rican workers assigned to build Fort Bragg in Fayetteville who succumbed to the 1918 flu pandemic. A few of the veterans are women. The burial ground once known as a Yankee Cemetery also now holds veterans from World Wars I and II the Korean War the Vietnam War and the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Honoring Heroes

A super-sized Captain America figurine rests at the foot of a well-decorated headstone. Sgt. Thomas Jefferson Butler IV known to family and friends as T.J. was the last combat veteran buried with honors at the Wilmington National Cemetery. Sgt. Jefferson was killed in action on Oct. 1 2012 while serving with the National Guard in Khost Afghanistan.

The Captain America doll perhaps belonging to the son he left at just 5 months old seems like an appropriate way to recognize Butler’s hero status. Like most buried in the graveyard alongside Market Street he died in service to his country.

“It doesn’t go away. The impact of someone giving their life for their country is not something that goes away ” says Bill Jayne a Wilmington resident who works as a consultant with the Department of Veterans Affairs giving presentations on national cemeteries.

Jayne spent 20 years planning new cemeteries and expanding existing ones all around the United States. In 2006 he left Washington D.C. and arrived in Wilmington where he worked inside the Wilmington National Cemetery’s old superintendent’s office for five years. He knows the cemetery very well. It’s almost as though he personally knows those buried here.

“That one has a ‘P.H.’ for Purple Heart so he was wounded or died in combat ” Jayne says pointing to a headstone. “This one is well visited.”

George Edwards a historian and executive director of the Historic Wilmington Foundation gets a first-hand peek at who frequents the Wilmington National Cemetery from his window in Jayne’s former office which was in the third version of the original superintendent’s lodge.

The superintendent was tasked with assisting families looking to reserve plots or bury their loved ones. The VA considers the cemetery full — although exceptions are made for those killed in action — removing the need for the position. Now the lodge is occupied by the Historic Wilmington Foundation.

Wearing spectacles a paisley bow tie and striped Oxford Edwards reflects on the visitors.

“Sometimes you will go a month with none sometimes you’ll have 10 ” he says.

Watching through his east-facing window he can see or assist visitors who drive walk or bike in and ascertain whether they will stay a while and visit ask a few questions to quench their curiosity or depart as abruptly as they arrived.

“Some African Americans pull in to see whether this is an African-American cemetery ” he says.

It’s not but of the 2 100 Civil War dead buried within the fence there are roughly 557 graves of those who are recognized as having fought served and died as part of the U.S. Colored Troops. Most of these soldiers remain unknown. Two of them — the officers situated at the crest of the hill — happened to be white.

Contentious Beginnings

To truly know and understand why 2 100 Union dead came to lie below the roughly 5.2 acres of sandy soil in a Southern state it helps to know history. During the conflict most casualties were buried where they fell in makeshift graveyards on battlefields. After the war those who died in service of the United State were reburied with honors in national cemeteries by order of Congress.

“The bodies had been taken out � by hearses wagons and drays ” says Chris E. Fonvielle Jr. Civil War historian and University of North Carolina Wilmington professor. “The battlefields had been swept by undertakers to find exhume and rebury the Union dead together although segregated by race within the cemetery’s brick wall enclosure.”

A post-Civil War cemetery only for the Union dead in a Southern state was met with resistance. Even finding land proved challenging. In 1867 the U.S. government bought five acres of land from Isaac Ryttenberg for $2 000.

“No one else wanted to sell land to the Army ” Jayne explains.

The editor of the Wilmington Daily Journal summed up the feelings of many when on May 31 1868 he wrote about the National Cemetery dedication: “The Southern people do not begrudge the money they pay in taxes to purchase and ornament the National Cemeteries and build monuments to honor the Federal dead. They only plead to be allowed to pay their meager tribute unmolested to their own cherished heroes; to erect the memorials of their affection and gratitude; to collect together the bones of their fathers brothers and sons from the fields of their glory and deposit them where the hands of love can garland their graves. They only ask in return for their payment to do honor to the Federal dead to be allowed to do honor also to their own soldier dead.”

Edwards notes that there wasn’t a call for Confederate dead to be allowed in the new cemetery.

“You could imagine the Civil War left a lot of hard feelings in this country which took a while to dissipate and families probably did not want to bury their loved ones who were Confederate in a Union cemetery ” he says. “You could understand the distrust — hate would be too strong a word but anguish and bad feelings.”

As a result for generations locals knew it as the Yankee Cemetery.

“Not until World War II did the cemetery break from being called the Yankee Cemetery ” Jayne says.

Jayne who served in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War says it was Pearl Harbor that changed the Yankee/Southerner terminology as men from every state collectively felt the call to arms when the United States was attacked. Regional differences were forgotten as they united to fight for their country. Some of the South’s soldiers who made the ultimate sacrifice in World War II were buried with full military honors at the Wilmington National Cemetery in the graveyard once reserved for Union dead.

Honoring the Fallen

The heart of the Wilmington National Cemetery remains the storied lives of those buried there.

“You can learn a lot about the people buried by reading the headstones; it’s simple to see many of the dead are considered heroes ” Edwards says.

Among the heroes is William A. Buck Sr. who served in the U.S. Army in World War II Korea and Vietnam. Next to him lies his son William A. Buck Jr. killed in action in 1969 in Vietnam.

“His sister still visits him and their father ” Jayne says. “He was a lifeguard at Wrightsville Beach and someone is leaving seashells next to the headstones.”

Nearby is the grave of Sergeant First Class Edward C. Kramer of Wilmington who died in 2009 at the age of 39 while serving with the National Guard in Iraq. Sgt. Kramer was buried with full military honors.

His widow Vicki Kramer visits often. She says it is an honor to have Ed as she calls him interred here.

“To be surrounded by people who were willing to die for their country which is a very brave thing there is great gratitude for everyone ” she says.

Although not official protocol Edwards says according to tradition “service members are buried facing the rising sun.” Every day the morning sun hits the east-facing headstones in the Wilmington National Cemetery illuminating the hallowed ground that resonates with the history of the heroes who lie beneath.

Remembering the Sacrifice

On a summer day spotted with showers a silver minivan with Ohio tags pulls into the cemetery. A family walks the grounds. They stoop over headstones point and chat with one another sometimes taking photos with their phones.

Clearly they are not memorializing anyone in particular but just exploring lured in by a highway historical marker at 2100 Market Street.

“That’s what drew us in ” says Meghan Dempsey a 16-year-old student on a mission to bring home a piece of Civil War knowledge to her high school history class.

She says her family spotted the marker that reads “UNITED STATES COLORED TROOPS — Black soldiers and white officers in Union army 1863-1865. About 500 involved in Wilmington campaign buried here.” Her sister Kellie asked their parents including her history-teaching father Scott “What kind of cemetery is that?”

Jayne answers their questions. In a button-down short-sleeved plaid shirt and beige cargo shorts wearing socks and sneakers he looks like he could be taking a tour of any city in the country. Instead he gives one. He teaches the two sisters about the U.S. Colored Troops who fought for Union forces but were buried in the South.

Hearing these words turned history on its head for Kellie a recent Ohio State University graduate.

“They didn’t teach us any of this in school ” she says.

A number of the U.S. Colored Troops who are buried at Wilmington National Cemetery are believed to be from northeastern North Carolina. Free blacks could enlist with the Union after the Emancipation Proclamation. Later in the war Union commanders began accepting runaway slaves into their regiments.

“They were North Carolina slaves who escaped ” Jayne tells the Dempseys. “They fought for the U.S. Army. They freed themselves.”

Sergeant Frederick Johnson known as Sgt. Fred a U.S. Navy veteran and Civil War re-enactor has ancestors who served with the Colored Troops. At 84 Sgt. Fred is the oldest member of the Battery B 2nd Regiment U.S. Colored Troops Light Artillery Civil War Re-enactors.

“I’m proud that my family served the country ” he says. “They served in the North from Pennsylvania free and fought on behalf of their country.”

Sgt. Fred reclines in an armchair in his Wilmington home surrounded by files folders and briefcases full of the past. He studies history and knows that after the fall of Fort Fisher in January 1865 two brigades of U.S. Colored Troops were among the 3 149 Union soldiers that marched on Wilmington. He knows that more than 500 died in the conflict with Confederate forces trying to protect the South’s last Atlantic port.

He wants their sacrifice to be remembered.

“The main thing and my concern is I hate to see any member of the military who served forgotten ” he says emphatically.

Sgt. Fred was instrumental in dedicating the historical marker honoring the Colored Troops that caught the eye of the Dempsey family.

Sitting in his living room with his wife Catherine Sgt. Fred points to assorted framed photos on the walls and TV console retelling days of traveling the East Coast with his regiment dressed as a Union artillery sergeant.

His navy blue Korea Veteran hat earned during 19-months’ service in Korea rests on a bookshelf nearby. It mirrors the navy blue Union Army uniform he wears during Civil War re-enactments. He likes the Wilmington National Cemetery because of its accessibility to all who wander by.

“The gate stays open ” he says.