Fishing for Research

A project to tag sharks off Shackleford Banks landed some interesting and dangerous species

BY Peter Perschbacher

The Research Vessel (RV) Machapunga was the largest, at 47 feet, and best built Harkers Island vessel I have seen and been on. She served the research community of the UNC Institute of Marine Science in Morehead City for many years. The Machapunga was beamy with a shallow draft, perfect for studies in the nearshore marine habitats and for the longest shark research study, started by Dr. Frank Schwartz in 1972 and still going.

I joined his Cape Fear River study in 1975 and helped with the twice-monthly shark longlining off Shackleford Banks. Dr. Schwartz was especially interested in sharks and, at the end of his life (2018), of stingrays and differences in their dangerous spines. He was fearless to a fault and related harpooning a manta ray and being pulled almost to the foaming reef when the line separated.

Shark fishing off Shackleford Banks was a day on the salty main, almost a pleasure cruise. But we were there to catch, measure and tag sharks. And we did, many more and larger then than now, unfortunately (for sharks at least). We used trawled bait and 6-inch hooks spaced on a suspended longline. While they soaked, we ate the best ham and cheese sandwiches I have ever had.

After an hour, we started to haul in the 100 hooks. When a shark was on, we called for Otis, the mild teddy bear of a captain, to cut the engines. Large sharks would visibly move the line, and the more the line was skewed the more anticipation for a large shark. In it came, usually thrashing and snapping like a dog. In my (comparative) youth I was barefoot but knew to watch the shark’s business end and no accidents occurred.

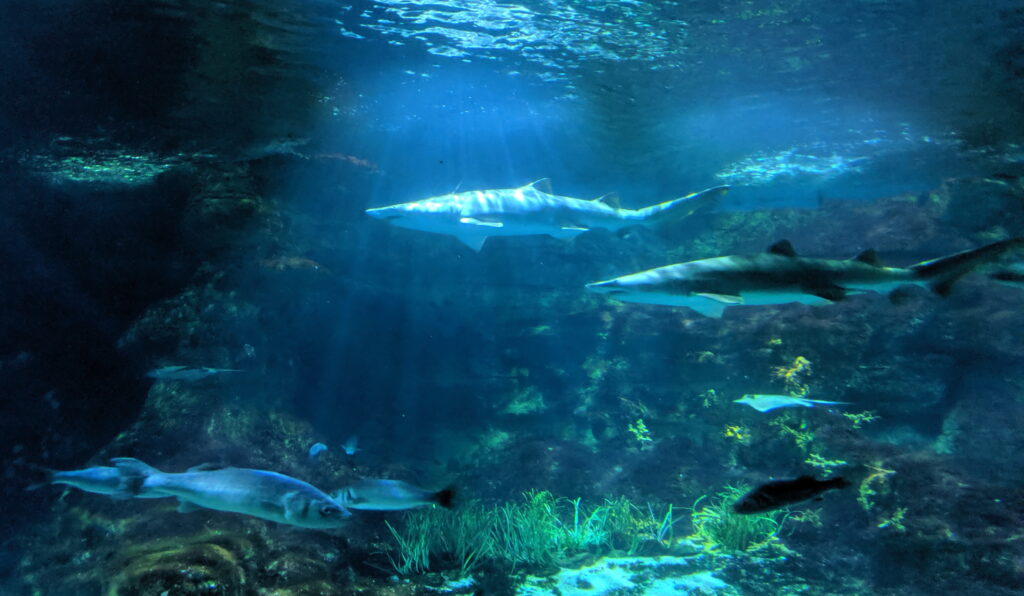

We measured and tagged them through the dorsal fin after getting the hook out. Then it was, “back it up Oty.” The majority were less than 5 feet and your standard shark design: sleek, pointed snouts, and gray. Differences between the more common sandbar, sharpnose, blacktip, dusky and blacknose were black tips and fin sizes and positions.

We also tagged the snaggled-toothed sand tiger with fishhook teeth for fish diets, the odd-looking hammerheads, and the largest of the catches while I was onboard, a tiger shark. This shark is the second largest non-filtering feeding shark in our waters, behind only the white. The largest of any kind are the uncommon whale and basking sharks. The biggest on record in the Cape Fear River was a stranded 40-foot whale shark at the inlet in 1934.

When we boarded the tiger shark, we had to use the winch. The shark was over 7 feet — large to us, but well under the North Carolina record of about 12 feet. What is unique about the tiger shark is its spotting and stripes. But more impressive is that the body is basically a broad head with saw teeth attached to a long tail. The business end means business.

All the live sharks went back into the water. If dead, they went to the collection at the lab. We never saw the great whites that patrol our shores and the mouth of the Cape Fear; many followed by their unique signals when their sonic tags surface. But the occasional half shark pulled up could only have been chomped by another much, much larger.

To add to these ominous unseen sharks, the movie Jaws came out the year I joined the study. It took a long time to look at the ocean in the same peaceful way again.