Close Call

The East Coast Nuclear Disaster that Almost Happened

BY Robert Rehder

During the evening of Jan. 23, 1961, newly inaugurated president John F. Kennedy held a strategy meeting with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy to discuss the growing threat of Russian nuclear escalation.

As they discussed the nation’s nuclear arms program, 272 miles away a United States Air Force B-52G carrying two massive Mark 39 hydrogen bombs was in the process of disintegrating 10,000 feet above Goldsboro, North Carolina.

Cold War Threat

President Kennedy had been in office for only four days. It was the height of the Cold War and a period of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. There was an ongoing struggle between the two superpowers for global influence brought about by a national perception that Russia might launch a preemptive strike with its nuclear arsenal.

The threat was real. It would take only about 30 minutes for a nuclear missile launched from Russia to reach the United States, or about 10 minutes if launched from a submarine.

One defense was a buildup of the American Strategic Air Command (SAC), which was responsible for the U.S. military’s nuclear strike force. That included land-based strategic aircraft armed with nuclear bombs. One of those American aircraft was the Boeing B–52G Stratofortress bomber. With eight jet engines that hung in pairs from four pylons and armed with a nuclear payload, the B-52G was a lethal, intercontinental, nuclear bomber. Some of them were stationed at Goldsboro’s Seymour Johnson Air Force Base.

Operation Chrome Dome

The fear of nuclear war was so severe during the height of the Cold War that the United States Air Force kept some 12 SAC aircraft in the air and on missions 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The exercise was known as Operation Chrome Dome. In the event of an attack, the airborne fleet could fly directly to predetermined targets.

The B-52s at Seymour Johnson were a critical part of that alert force. To keep them airborne for extended flights, the planes were fitted with integral fuel bladders installed in the wings that could be refueled in midair.

Crew

On the morning of Jan. 23, 1961, the eight airmen who crewed the B-52 named Keep 19 were going through final flight checks before departure from Seymour Johnson on an airborne alert mission. They climbed aboard the giant bomber and prepared for takeoff.

The flight commander and pilot was Maj. Walter S. Tulloch with pilots Capt. Richard W. Hardin and 1st Lt. Adam C. Mattocks. Other crewmembers were Maj. Eugene Shelton, radar navigator; Capt. Paul E. Brown, navigator; 1st Lt. William H. Wilson, electronics warfare officer; Maj. Eugene H. Richards, electronics warfare instructor; and Tech. Sgt. Francis R. Barnish, gunner.

Tanker Rendezvous

Flying along the Eastern Seaboard, the flight had gone well with no complications. Later that evening over the North Carolina coast, Keep 19 was in the process of midair refueling with a KC-135 tanker aircraft. Then, the KC-135 pilot reported a fuel leak in the B-52’s right wing. The added stress from the additional fuel bladder was about to cause a fatal accident. When fuel began streaming from the wing, the refueling operation was aborted. After dumping most of its remaining fuel the plane was directed by air controllers to return to Seymour Johnson.

Bail Out

Though critically damaged, the right wing remained intact as the giant bomber started its approach to the base. The plane was at 10,000 feet when flight commander Tulloch engaged the landing flaps.

The B–52G’s landing flaps have only two positions — full up and full down. When the flaps moved to full down the damaged wing ruptured and sheared off, and the pilots lost all control of the aircraft. Maj. Tulloch immediately ordered the crew to eject.

Standard equipment for the bomber includes six seats equipped with escape hatches and ejection systems. The plane is designed to enable four crew to eject from the upward-firing top hatches and two from the belly hatches below, clearing them from the plane before their parachutes automatically opened. Six of the eight personnel aboard Keep 19 sat in ejection seats. The other two would have to secure a parachute, make their way to any open hatch, and jump free. Upon Maj. Tulloch’s order, all six crewmembers in ejection seats bailed out at 9,000 feet.

The First Bomb

As the plane began to disintegrate, the two Mark 39 nuclear bombs separated from the aircraft.

In the case of an accident, and to avoid a nuclear disaster, both bombs had a series of arming mechanisms. One of those mechanisms was a parachute that activated when the bomb was released from the plane. The parachute was required to slow the bomb’s descent so the aircraft could safely fly out of the blast zone.

The first bomb fell free with no parachute and dove at some 700 mph into the ground at C.T. Davis farm near Nahunta Swamp in rural Wayne County. It partially broke apart on impact and torpedoed through the wet earth to a depth of some 50 feet, leaving a cavernous crater. Even with the intense shock at impact, none of the conventional explosives designed to sequentially trigger the nuclear explosion activated.

An Air Force explosive ordnance disposal team would remove components from the crater, and government contractors would attempt to excavate the hydrogen core. But the crater was in a swamp with a high water table, and it flooded so quickly that excavation work had to cease. Eventually the decision was made to fill the crater with sand. The Air Force would purchase an easement with restrictions on any activity other than farming. Components were salvaged, but the bomb itself remains entombed in Nahunta Swamp along with its nuclear core.

The Second Bomb

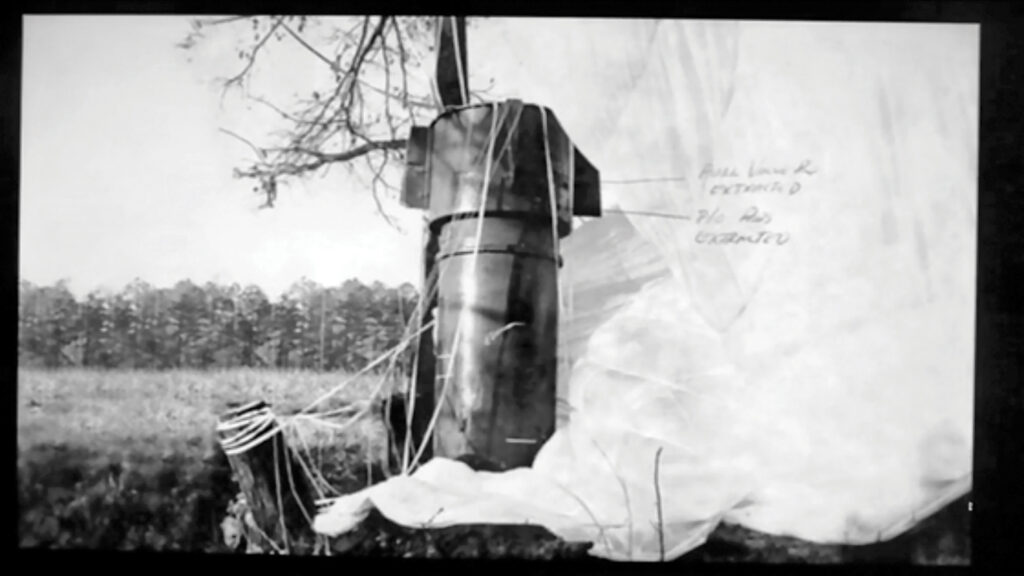

The second bomb presented a different and very chilling possibility. The parachute activated, meaning that the bomb had started the process of arming itself. But for one simple electrical switch, what happened next might have led to a nuclear explosion in North Carolina.

The parachute allowed the bomb to land upright and undamaged in trees bordering Shackleford Road near the small rural town of Faro in Wayne County. After diagnosing the bomb with high performance sensors, an anxious explosive ordinance disposal team determined the device was not armed and transported it back to Seymour Johnson, releasing little information.

Details of what happened in the arming process were a closely guarded secret for more than 50 years. Then in 2013, information was released confirming that of the six arming devices within the bomb, only the failure of a single switch that was the final step in the arming process prevented detonation. In a now-declassified 1969 report titled Goldsboro Revisited, Parker F. Jones, a supervisor of nuclear safety at Sandia National Laboratories, wrote “One simple low voltage switch stood between the United States and a nuclear catastrophe.”

Crash

Remnants of the B-52 crashed over a two square-mile area of tobacco and cotton farmland along the towns of Faro, Patetown and Eureka some 12 miles north of Goldsboro. Five of the eight crewmembers survived — some with critical injuries. Maj. Shelton perished in the jump and Maj. Richards and Tech. Sgt. Barnish died in the crash. Lt. Mattocks successfully parachuted out of a top hatch in the plummeting plane, the only B-52 pilot ever known to have survived such an escape.

Epilogue

Today, a serene pond nestled in a Faro forest belies the horror that rained down that January night. A state historical marker is the sole physical reminder of the deadly accident that took the lives of three brave U. S. airmen and brought the North Carolina coast tragically close to a terrible fate. Nuclear experts estimate that the blast would have instantly killed everything within a 15-mile radius, and lethal radiation fallout could have traveled throughout the Atlantic seaboard with devastating consequences.

At the crash site, the sleepy verdant land has swallowed up any sign of disaster. The peaceful, rural setting instills a confidence that the incident was not all that critical, and the safeguards were programmed correctly to prevent a catastrophe. That idea might seem strange to the commanders at SAC who held their breath that night as the second bomb began to arm itself.